Games of 2013 (8/10)

A few of the games we liked last year.

There were a lot of great games in 2013. Far too many, in our opinion, for a list of five or ten, or to declare one our definite champion. Even a list of fifty would not do them justice, but we compiled one anyway. Continuing on from last week, we’ll be highlighting five games a day, Monday to Friday. No ranks or numbers, they are all equally close to our hearts.

Metro: Last Light

Reinvented spaces are the inalterable cross-stitch of Metro: Last Light’s post-apocalyptic tapestry. So it is that a subway becomes a home, a storage cart a people-carrier, a plane a coffin. Even the objects within these spaces find themselves subject to unusual reinvention as a bicycle becomes a gun or a bullet currency. But in Last Light, this duality of terms belongs to the temporal as much as the spatial, employing what modernist writer Jean Rhys once described as, “the past [existing] – side by side with the present, not behind it; that what was – is”.

Indeed, it’s memory and nostalgia that form Last Light’s true thematic substance. How, in a place paralyzed between traumas both new and old, between experiences personal and societal, do you put a stake in reinstating normalcy? While protagonist Artyom’s impressions of the pre-apocalypse are filtered through his memories of his mother and childhood, the world around him is left to recall the moment of its own destruction. A downed plane and its passengers are not simply a passive reminder of what once was, not to mention the crashing halt it came to, but are themselves trapped in an endless transition from transitory space to resting one – from old world to not-quite-new.

Last Light itself was trapped in something of a transitionary period upon its release. Despite arriving two months post-Binfinite, critics had yet to almost cause their own mini-apocalypse in debating Last Light’s controversy-courting contemporary. As a result, Last Light’s presence in the critical space was relatively absent. Unlike Infinite’s often flailing, sometimes catch-all approach to theme however, Last Light’s was one of confidence, quietude and contentment. And for that – for managing, in a sense, to appear quite so ordinary – is enough to make it truly extraordinary.

Bioshock Infinite

The internet would have you believe there are two sides of thought to BioShock Infinite: it’s either an intellectual giant, or an uncomfortable polemic that sums up everything wrong with the AAA games industry. It’s not really either of those things.

BioShock Infinite is one of my favorite things – educated genre fiction. Ken Levine is not a titan of thought, unleashing daring and poetic works that shape a medium, if not a society. His games are based in genre – System Shock 2 in hard sci-fi, BioShock in horror and Infinite in all manner of things – but with complex thematic underpinnings. BioShock Infinite is an action game about guilt, about the consuming desire for legacy and about a country that would rather embrace its shame and exploit it than ever confront it. It is also a game in which you fling yourself around combat arenas and set people on fire.

I can understand the disconnect and I can understand the disappointment. But personally, I love that mix. I love the feeling of a game crafted by literate adults for literate adults, but still retaining well executed and potent genre qualities that I can enjoy and indulge in. BioShock Infinite is neither the most potent piece of fiction on its themes, nor is it the most accomplished first person shooter. But it’s the way the game works as a whole, interweaving the action with the denser themes and real emotion that left me amazed by the end. Perhaps it’s not the great piece of art it was proclaimed to be, but Bioshock Infinite was exciting, propulsive and evocative.

Knock-knock

Stephen King famously drew a distinction between three kinds of horror: “The Gross-out: the sight of severed heads tumbling down a flight of stairs […]. The Horror: the unnatural, spiders the size of bears […], it’s when the lights go out and something with claws grabs you by the arm. And the last and worst one: Terror, when you come home and notice everything you own had been taken away and replaced by an exact substitute.” Most AAA games indulge in the Gross-out, while the recent wave of frightening indie games focused on the subtler aspects of Horror. But it took a bunch of Russian bedroom programmers and an opaque Kickstarter campaign to give videogames the purest expression of King’s worst category yet.

In Knock-knock, a hermit – as lonely in his mansion as he is lost in his own past and mind – serves as the player’s mirrored window into a world which is uncanny even in the bright light of day. Come nightfall, the underlying sadness turns into madness, when the voices inside the hermit’s head start growing legs, arms and disfigured faces. Suddenly, what used to be home turns into an abyss, and all you can do is stumble around, trying to hold the shadows at bay, until morning comes with a shimmer of hope and fleeting sanity.

Knock-knock masterfully evokes the terrors that loom behind closed eyelids, not only with an excellent soundscape and wonderfully weird visuals, but also with the arcane systems so typical of Ice-Pick Lodge’s games. They are put to excellent use here: even if you manage to make it through the nights, Knock-knock never feels like something that you have mastered. And how it could it? Terror is not something to be understood. It’s that looming feeling you can’t get rid of, try as you might.

– Christof Zurschmitten, Go to Haneda

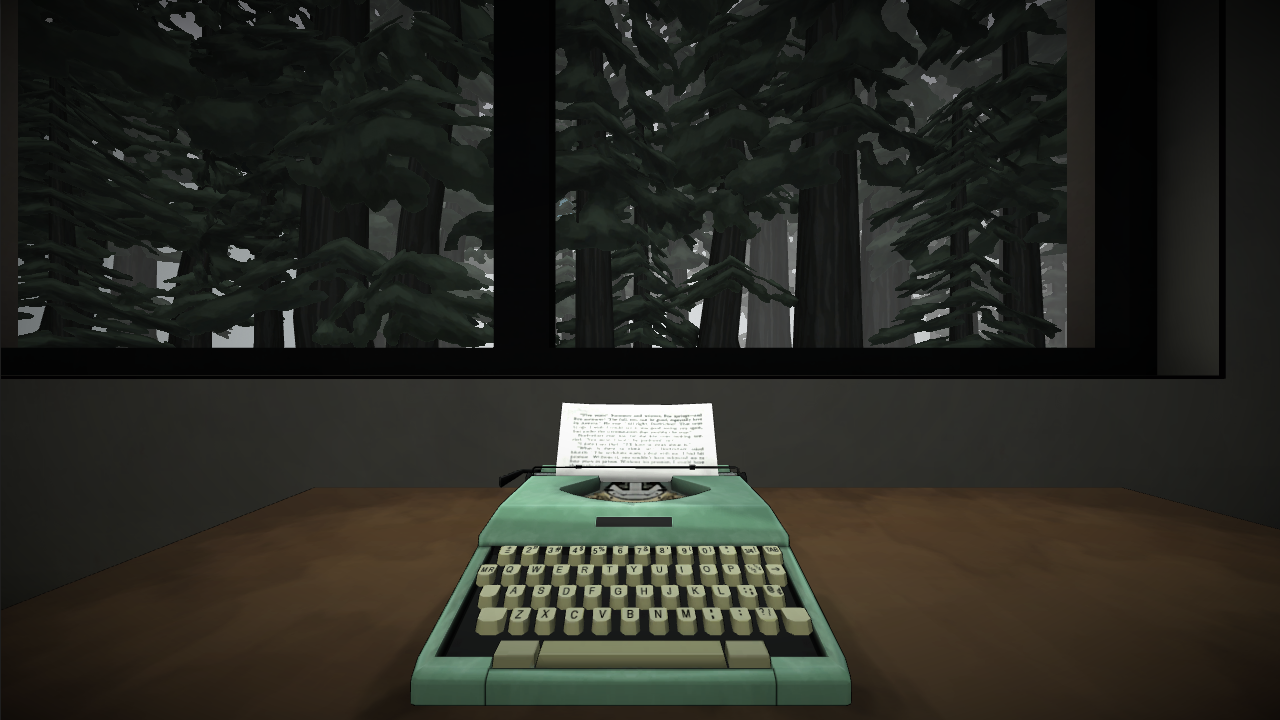

The Novelist

In The Novelist, Dan Kaplan and his family have moved into a rental property in the Pacific Northwest. Dan did so with intent of finishing his novel, a sophomore effort that will make or break his career as an author. But his professional goals are hampered by a troubled family life – his relationship with his wife is beginning to sour and his son is slipping behind in school. As the invisible choice-maker for the family, the player gets to decide whether Dan puts more effort into repairing his family or his creative aspirations, with effects cascading to the other family members and well beyond that fateful summer.

It’s a game that wants to confront players with choices where no answer appears to be the right one. How do you choose between your son, your marriage and yourself? How do you find a healthy balance between responsibilities of work and home knowing that you’ll need to disappoint someone some of the time? Is it more noble to chase your dreams while sacrificing the relationships you hold dear, or to help others achieve all that they can at the expense of your own ambitions?

The game walks a fine line between letting players explore these ideas and dictatorial rhetoric. The amount of effort and sacrifice required to make the novel anything above mediocre is intentionally skewed quite high, suggesting the costs Dan must pay to achieve his vision are too high. And while the player can make Dan neglect his book for a whole playthrough and succeed in saving his personal life, if he neglects his family outright the game will end early as his marriage falls apart and his wife and child leave him. Still, the game’s subtle enough in its application of these mechanics that the author’s opinion shines through without crowding out the player’s ability to find their own answers to those questions. Approached with the right mindset and a sympathetic ear to Dan’s conundrum The Novelist can be a rather provocative work.

– Chris Franklin, Errant Signal

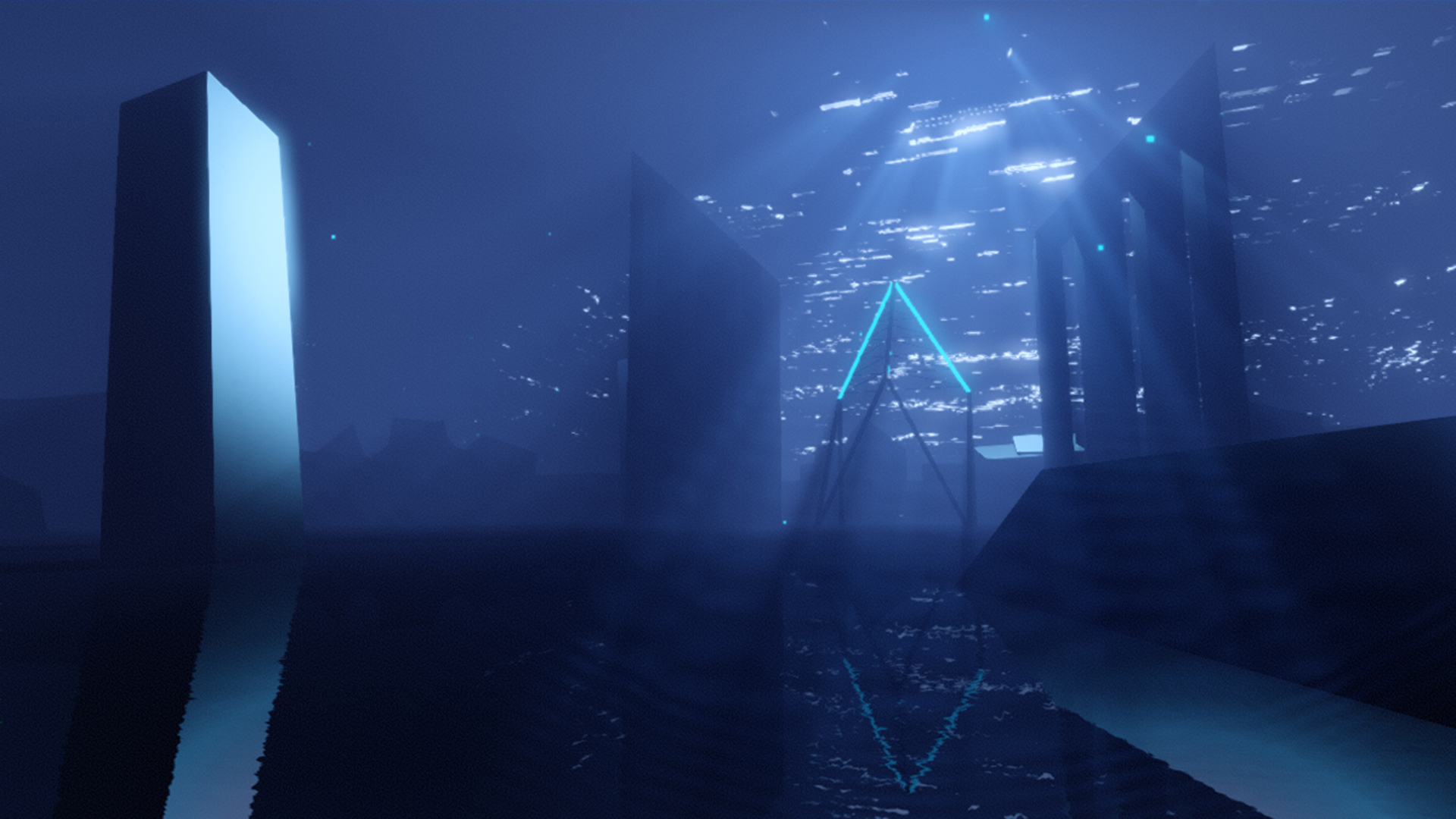

Master Reboot

Master Reboot caught my eye in the Steam Store a few weeks before its release. The screenshots and summary suggested a bright alternative to cyberpunk, one not driven by dystopian corporatism. What completely blew me away, however, was the premise of a world that had, at least partially, found a way to overcome death through technology. As you might expect, the hubris that goes along with such a groundbreaking invention manifests itself in a beautifully moody game that integrates its more sinister undertones exceedingly well into its majestic spaces.

The game takes place in the Soul Cloud, an online social media service that houses the souls of people who have passed away in the analogue world. Master Reboot never explains how this is supposed to work, nor does it have to: the mere implication that humankind has found a way to capture a living soul in statistical data stirs up player imagination significantly. Souls are not only uploaded for self-preservation, they are conscious and alive, and relatives can go online and revisit memories together.

These memories make up the structure of Master Reboot. Starting the game, the first-person perspective makes it deliberately unclear who the protagonist is or why you are in the cloud. The player is forced to solve simple puzzles that range from refreshing chase sequences and dark labyrinths to frustrating exercises in finding or matching objects. A hub area serves as an access point for the different memories that are unlocked in sets.

Unfortunately, much of the game’s more overt storytelling is restricted to text in collectibles, which can be hard to find and care about. It’s the fresh visual design that ultimately creates the impression of a compelling world filled with sometimes gorgeously evocative scenes; a vision of a union between glitch and memory.