Games of 2013 (3/10)

A few of the games we liked last year.

There were a lot of great games in 2013. Far too many, in our opinion, for a list of five or ten, or to declare one our definite champion. Even a list of fifty would not do them justice, but we compiled one anyway. Over the next two weeks we’ll be highlighting five games a day, Monday to Friday. No ranks or numbers, they are all equally close to our hearts.

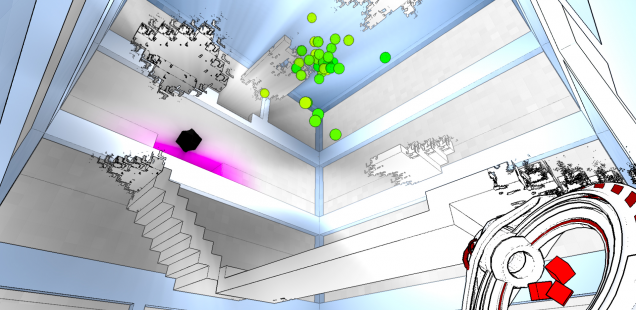

Antichamber

If Aliens: Colonial Marines showed us anything, it’s that, in videogames, what you see isn’t always what you get. But that kind of deception can be a good thing when it’s part of the game itself and not its packaging, and Antichamber is certainly honest about its plans to mess with your head. It pulls the carpet out from under you, and over you, until you realize the carpet is actually a Moebius strip.

The game’s big bag of quantum trickery combines optical illusions with mechanical mirages, and in doing so offers a delightful break from the tyranny of objective camera. So tight is its grip on games that we even class them accordingly: Perspective is not a narrative term here, but simply denotes where the simulation places our digital eyes. Outside of the openly hallucinatory, clearly marked by its psychedelic visuals, the idea that our view of the world and our view into a world might be unreliable is abhorrent, since the concept of vision is linked so strongly to the power structures of games. Seeing is aiming, and aiming is killing.

Not so in Antichamber, where your gaze is the hopeless attempt of pinning down an entirely unreliable, winding labyrinth. You can trust neither your eyes nor your legs: paths and obstacles change depending on where you are and where you are looking. Once you adapt to your unstable surroundings, what remains of Antichamber is a ruthless puzzle game, in the truest sense of the words. It offers you no hints, no visible goal and no sense of direction. Only meditative platitudes administered a second too late, after you solve, or break, the puzzles they describe.

Antichamber is not the kind of game to make you feel clever for filling in a few blanks. It’s a riddle wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma. If you make progress at all, it happens despite the game’s efforts as much as because of them, and you feel like a supergenius from space.

Saints Row IV

Saints Row IV

No series is quite so self-aware as the Saints Row franchise. Even the Metal Gear games, rife though they are with allusions to the fourth wall, seem to have become so mired in their own internal mythology and self-seriousness that a proper critique proves elusive to them. Not so with Saints Row – its fourth game begins by openly referring to its own humble beginnings as an unremarkable Grand Theft Auto also-ran; a “pretender to the throne” in the world of sandbox games.

Now by this fourth entry, Saints Row has settled into a defined role: as a low-brow comedian getting away with high-minded barbs. Where Grand Theft Auto V kept billing itself on the breadth and texture of its simulation, Saints Row IV took delight in pointing out just how shallow a sandbox’s interactions were. Where other franchises lay on gruesome scenes of torture or war crimes, as Jeremy Parish points out, Saints Row IV’s most-discussed scene is a duet to Paula Abdul’s Opposites Attract. There is both a spiritual lightheartedness and critical deftness to Saints Row IV’s design that is hard to find in any other game, far less in such quantities.

Granted, judging the game by its individual components, nothing about Saints Row IV is particularly well done or inspiring. It’s when Saints Row IV is taken together – its joyously abrupt transitions from Call of Duty to Pleasantville to The Matrix, its Dubstep Gun and its live-action puppetry in place of CG cutscenes, its ‘romance system’ which consists only of hitting a single button to initiate casual sex – that it becomes something special. It is an unruly mess, but it is so in a way that reveals just how contrived the restraints of other games are.

Why do so many games struggle with putting women and people of color into starring roles, yet Saints Row IV can do both these things and have superpowers, UFO joyrides and dramatic readings of Jane Austen? The fact that there isn’t a good reason for it is at the heart of the game’s critique: Saints Row can do all these things, and so much more, without worrying about losing its audience, so what, really, is the industry’s excuse?

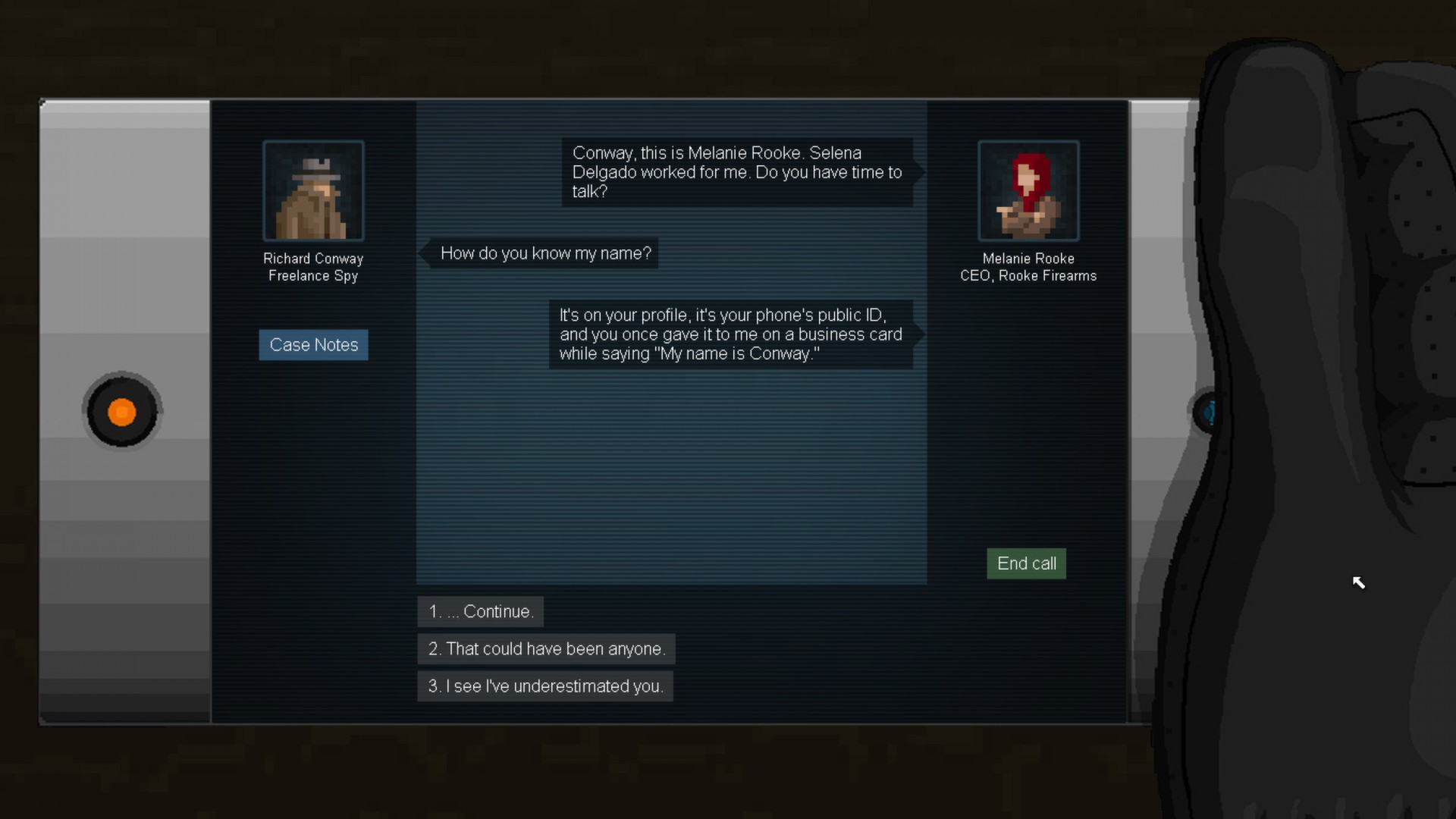

Gunpoint

The highest praise I can give Gunpoint is that it’s one of the sharpest, most thoroughly engaging blasts of a game that I’ve encountered not only last year, but since the first Portal.

It’s not all about the short, punchy (so very, very punchy) length. The short playtime is simply a consequence of finely honed 2D design. Sure, gadgets accumulate and the ingenious crosslink system allows an impressively wide range of interactions with the environment, but security systems are gated so intelligently, yet innocuously, that a methodical approach to dismantle the technoapparatus between you and your goal swiftly comes into view. Compartmentalized architecture and computer systems give the condensed levels a legible, natural arc.

And puzzles are solved not only by the contents of your brain but also with the equipment you’re packing in your trousers. Uh, let me rephrase that. Fitted with patented Bullfrog hypertrousers – incidentally the best comedy trousers outside of Wallace & Gromit – private investigator Conroy could walk, like an unimaginative trenchcoated shmuck, or he could launch himself with both reckless abandon and mouse-guided accuracy, propelled by treacherously bouncy legwear.

This sense of whimsy runs through the game without ever taking center stage. It’s in the tiny exasperated pause each time Conroy gets to his feet off the ground. It’s in the comic mission interludes that take dialogue trees and make them fun again. Sure, the conspiratorial plot amongst the relentlessly cunning dialogue is fairly convoluted and nondescript in itself, but with a genuinely funny riposte to every question, the typically slight videogame logic doesn’t matter.

It may never expand to the scale of last 2012’s Mark of the Ninja, or other fine 2D puzzlers, but nothing else last year matched the invigorating effect that a couple of evenings spent with this playfully evocative techno-noir adventure had for me.

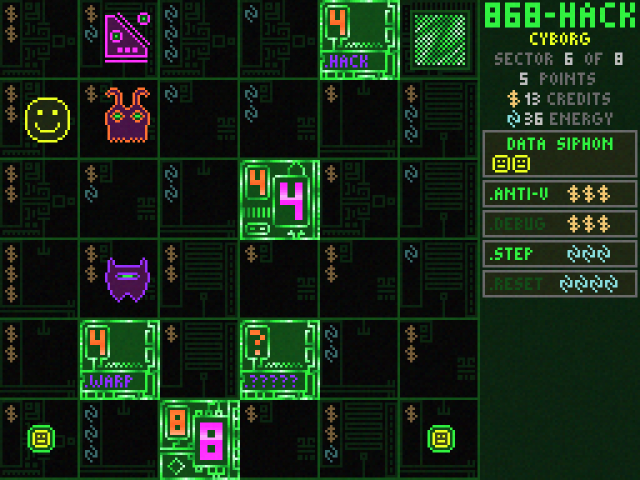

868-Hack

Imagine a parallel universe, where game design is a philosophy and making games is a universalist scholarly endeavor undertaken not for mere profit or entertainment, but with an earnest conviction that borders on faith. In this parallel dimension, to play a game is meditation, to become lost in these carefully constructed binary cathedrals is pilgrimage in the footsteps of the wizened dev-monks who spend their whole lives submerged in their worship of the thousand game faces of God.

Michael Brough’s 868-Hack is one such game.

Imagine yourself a novice in the temple of the Roguelike, studying this particular procedural neon death labyrinth. At first glance, it’s an artefact of maddening stubbornness, with ugly, brutish graphics and deceptively simple rules – traverse eight arenas of six by six squares, filled with resources, tools and four kinds of respawning enemies. Through trial and error, in a classic arc of discovery and permadeath, you slowly begin the path to mastery. You learn to read the movement patterns of your enemies, you realize that each of the many tools you uncover are powerful if used correctly. You learn to balance risk and reward, until you inevitably become too arrogant for your own good.

868-Hack combines strictly logical puzzle gameplay with brutal randomization and a wide variety of possible playstyles. It is an ever-changing, complex test of focus, intelligence and perseverance. It is a strict master, with its very own, deadly sense of humor: it rewards successful players with stronger and faster enemies.

At this point, the fervent novice realizes that 868-Hack’s apparent ugliness is deliberate. In this, our own universe, Michael Brough, with his hermit beard and a monk’s mischievous smile, is offering 868-Hack as a koan in the shape of a perfect game.

– Rainer Sigl, Video Game Tourism

Rune Factory 4

Rune Factory 4 damn near took my game of the year for 2013. While its concept seems simplistic, the sheer scope and design of the game makes concept and execution come together in a near flawless manner. Rune Factory, in its conception, branded itself as a fantasy Harvest Moon and the latter installments have embraced that label. You can farm and tend to animals, but the depth of the RPG elements, boss fights, dungeon crawling and plot give the game so much more depth than the series it claimed to emulate.

Another thing that sets Rune Factory apart from most games in its genre is the sheer amount of post-plot gameplay there is. While there is obviously tending to one’s farms and animals, there are also high leveled dungeons for those who love the escalating difficulty in the search of high rewards, new recipes and crafting plans to collect and monsters to tame. At the end of it all, Rune Factory 4 seeks to do everything and almost succeeds in that endeavor. To call it a sublime sum of its parts is the most accurate description one can give to it.

While I enjoyed this game enough to almost give it the number one spot of 2013, the European readers of this should know that the publisher currently has no plans to bring it to your shores. For this I say shame on them.