2017: The Year of Relaxation

Kick back and relax with A Road that May Lead Nowhere, Picross S, Everything, Block’Hood, Slime Rancher and The Norwood Suite.

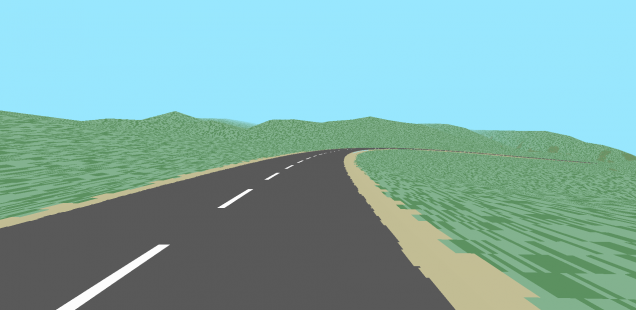

A Road that May Lead Nowhere

Ian MacLarty’s A Road that May Lead Nowhere is a driving game that borrows from a legacy of walker games such as the similarly low-polygon, pastel-colored Proteus. The game features no objective other than to drive down an endless road without destination or other vehicles. As such, the game compels players to engage in the mundane pleasure of driving and – given the lack of stimuli other than the passing landscape – pondering. Its slowness evokes the feeling of a road trip, embracing uneventfulness and boredom alongside short moments of the sublime.

Because the game is procedurally generated with a short draw distance, A Road that May Lead Nowhere presents us with a series of topographical unfoldings. Mountain parkways tumble into bucolic valleys that flatten out into desert straightaways, the road disappearing with the horizon or curving in a wide arc across a treeless plain. As the game gently progresses through day-night cycles, the sky changes hues from midday blue to the warm, orange afterglow of twilight.

Released without audio, the game expressly tasks players to curate the road trip music, thus encouraging us to direct the mood of the entire experience and evoking past memories of travel. What songs do we remember listening to with family or friends during long trips? What songs awaken nostalgia for an open road?

Two summers ago, I drove with my father across the United States to move to California. Highways dovetailed with the historic Route 66, sprawling westward across sparsely populated grasslands and deserts before spilling into the suburbs of Los Angeles. While playing this game, I remembered the terrifying thunderclouds that engulfed the skies above Oklahoma, casting shadows hundreds of miles long. I remembered the skies turning orange to purple as we rocketed into Flagstaff, Arizona, racing the sunset. I remembered John Denver imploring country roads to deliver him safe passage home, his words pouring out from the radio. A Road that May Lead Nowhere stirred these memories, along with many other reminders of the past, and it is for this reason that it’s one of my favorite games of 2017.

Miguel Penabella is a PhD student investigating slow media and game spaces. He is an editor and columnist for Haywire Magazine. His writing has been featured in Kill Screen, Playboy, Waypoint, and Unwinnable, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.

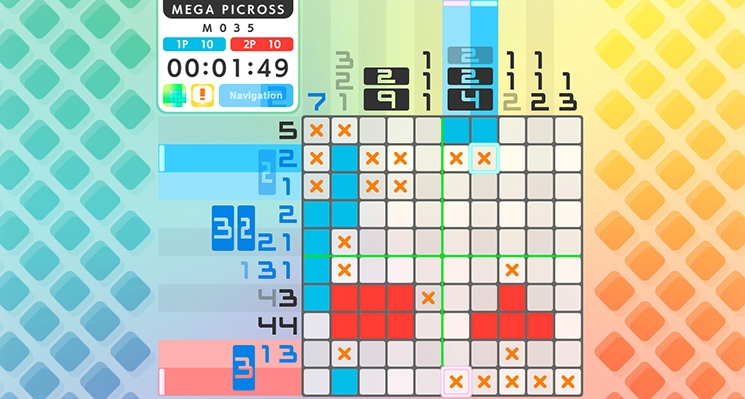

Picross S

I had a three-month stretch where I played Picross S every morning. It started that I’d sit down with my breakfast and coffee and knock out a puzzle. Then two. Then three. Then I was postponing work because I spent too much time every morning knocking out puzzles.

During those three months, my day job fell apart around my head and I poured endless energy into creative projects that hit dead ends – not because of Picross, I can’t stress that enough. I was not that far gone. But for fifteen, then thirty, then sixty minutes a day, I could wrestle with 15 by 15 grids while elevator jazz quietly looped in the background. Picross S was reliable and helped me keep steady, even during the hours upon hours I spent trying to solve P091. I still haven’t solved it – that specific puzzle is a nightmare, with its 8/1 and 9/1 verticals and its 4/1/1 and 6/1/1 and 4/1/4 horizontals. I might never find out what P091 is meant to be.

I’ve logged “Forty hours or more” on Picross S. It’s the most-played game on my Switch – I’ve played it more than Super Mario Odyssey, Mario Kart 8, Splatoon 2. It’s like at the start of Collateral, when Jamie Foxx talks about the island he goes to for five, ten minutes a day to escape. Picross S is my island.

Except for P091 that is the most bogus shit I swear

Adam Goodall is a freelance writer, editor and legal publisher based in Wellington, New Zealand. He writes about New Zealand theater for The Pantograph Punch and about videogames, the internet and the justice sector elsewhere. You can follow him on Twitter if you’d like.

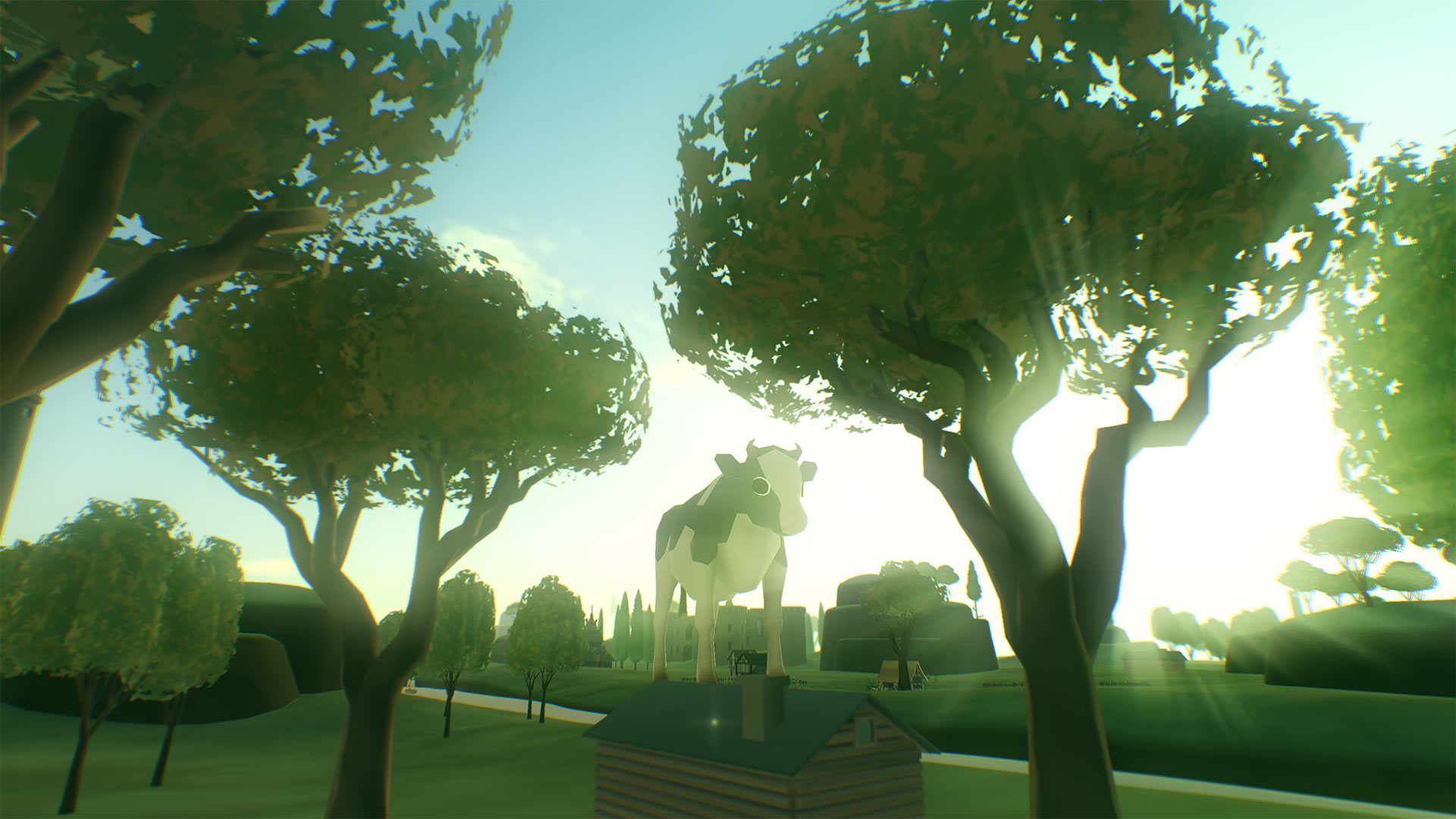

Everything

The tallest building in the city spontaneously transforms into a chicken. A lone shark swims through a watery darkness lit by a million streetlamps. All the bees balloon exponentially in size until each is as big a truck. The heart of Everything is imagery, and every time I load it up it finds new things to show me, ranging from funny, to melancholic, to terrifying. This game is known for its presentation of the soothing philosophy of Alan Watts, but maybe what I’ll always remember most vividly is the time a too-large snail’s movement glitched out, causing it to jitter wildly between two places. The systems by which the game generates new things to see are powerful, and I’ve learned to race through the menu to reset things when what appears gives me the willies. It has been a long time since a game could make me aware of some obscure, hyper-specific phobia of mine.

The first thing you notice when you start playing Everything is the goofy way most of its animals move – rigid bodies performing jagged cartwheels, a throwback to David OReilly’s The Horse Raised By Spheres. I stopped noticing that after a while: a family of zebra pop and lock their way over a sand dune, and all I see is the majesty of nature. There aren’t any rules here to make you feel like you really are a brown bear or a pine tree or a jumbo jet, no complex ecosystems of predator and prey, no commerce, no special relationships of any kind between two different beings. It’s when these surreal images start to feel naturalistic that the being feeling emerges. I’m a snow fox, idly searching through the woods. What do I feel when a pair of headlights peeks over the hill ahead?

Joshua Trevett is a freelancer and the managing editor of Haywire Magazine. He mostly likes art when it’s weird, and that goes double for videogames. His writing can be found in publications like ZEAL and The Arcade Review. For secret reasons, it would be best if you followed him on just two out of these three social media sites: Twitter, YouTube, and his blog.

Block’Hood

Since going freelance late last year, I’ve become anxious about time. I have a Google Calendar and I use all twelve colors. I agonize over it, meticulously moving red blocks of contract work around every few hours, analyzing the white space, filling it with green and yellow and grey. I worry a lot about how I use the white space that I have; I’m convinced I’m not using it ‘well enough’. It’s affected how I read, how I watch, how I play. I’m impatient. Sit me in front of a game for an hour and it’s minutes before I’m looking for ways to maximize my returns.

Late last year, in a sort of grim irony, I also got into three games that ate into my time and my headspace without me realizing: PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds, Splatoon 2 and Picross S. Thirty minutes turns into two hours and I’m admonishing myself. This was wasted time. You could’ve done some work, played something interesting, but instead you leveled up your Splooshomatic to ‘Fresh’. You dumbass. You absolute fool.

This is all to say that I bought Block’Hood, a neighborhood builder with an emphasis on sustainable, ecologically-minded development, with the intention of making work out of it. But that intention messes with your ability to actually play the game that Plethora Project have made. I tried to race through the story mode and I embarrassed myself. My neighborhoods fell into disrepair as I recklessly built supply chains of humanity: build a field of solar panels and output Electricity; build ten large apartments, suck up that Electricity and output Youth; build three basketball courts for the Youth and output Community. My people left, my buildings crumbled and my communities died.

I brute-forced Block’Hood’s story and moved on to its first Challenge. On a simple 5×5 grid, you’re given a small selection of blocks – water towers, solar panels, corner stores, trees – to produce 250 units of water. Plethora Project have graded this challenge. They say it’s easy. So I tried to rush it like I rushed the story mode, suffocating the grid with blocks, deleting and rebuilding when they were exhausted. I lost, every time. It took me twenty minutes to realize that the only way to beat this challenge is to wait. You don’t use all the blocks. You don’t cover every square with construction, with ‘progress’, with stuff. Your impatience is greed, and it’s destructive. You only use what you need. That will be enough.

So I didn’t use all the blocks. I paced myself. I only used what I needed. And even though it took a little longer, no-one left, nothing died and I didn’t feel like I’d wasted my time. I was patient, and Block’Hood rewarded my patience.

Adam Goodall is a freelance writer, editor and legal publisher based in Wellington, New Zealand. He writes about New Zealand theater for The Pantograph Punch and about videogames, the internet and the justice sector elsewhere. You can follow him on Twitter if you’d like.

Slime Rancher

The basic premise of Slime Rancher, a game about wrangling sentient orbs of goo on a distant planet, quickly turns into either a chore or, worse, a depressing factory farm. That’s not to say that Slime Rancher is a bad game, but that the real charm of it lies outside its gamelike elements, its progression and crafting systems. You are more likely find joy in the chance to explore and observe an entirely alien ecosystem, to discover new areas of the planet, populated by new kinds of colorful creatures.

This medium can leave us so starved for a game that puts its tight movement and detailed physics simulation in service of something other than guns and explosions that a game about bouncing around an alien world alongside cheerful blob creatures feels downright revolutionary.

Joe Köller used to write about games, but he recently pivoted to video. You can find him on Twitter.

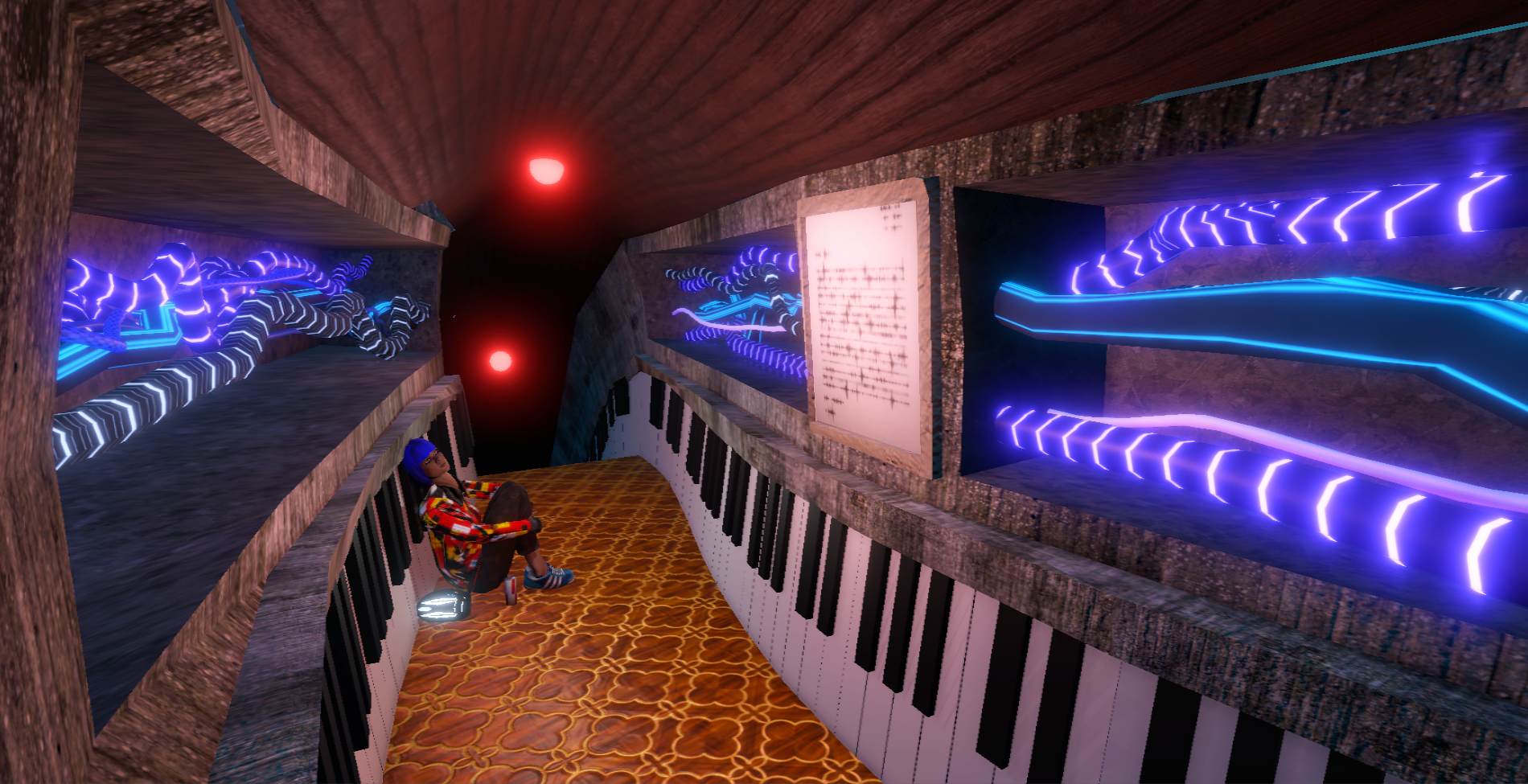

The Norwood Suite

Precarity and labor woes proliferate in The Norwood Suite, Greg “Cosmo D” Heffernan’s surreal getaway to the eponymous hotel. Staff members speak of not being paid for weeks and the inevitability of layoffs when the shady corporate firm Modulo arrives to take over. When the front desk badmouths the player-character, another employee fears the repercussion of a bad review on Traveller’s Quarterly, suggesting that the hotel loyalty rating could be put into a “precarious bracket.” Nearby, a band discusses how algorithms generate followers on social media to attract concert promoters, but worries that the health issues of one member will prevent them from playing an important musical festival. The Norwood Suite reflects a world in which professional livelihoods are bound up in complex issues and technologies, where employees are pressured to perform emotional labor, appearing constantly grateful and doting despite fears of unemployment.

Like Cosmo D’s previous game Off-Peak, your role is that of an interloper, here conscripted into work. Characters order the player to fetch objects such as alcohol or music to keep their minds off workplace anxieties. Thus, fetch quests are reconfigured as unskilled labor. Only mischief can undermine corporate interests, such as sabotaging a DJ set or uncovering secret passageways by pushing levers, buttons, and other perplexing gizmos. The game rewards curiosity, coaxing players to discover tangled hallways and oddities such as an impossibly long drawer, a Wi-Fi router manual that doubles as a poetry book (shades of Kentucky Route Zero here), or giant bowling pins that serve as piano keys. Despite characters’ unease, the atmosphere of the game feels like a constant rave. The dialogue system is joyously musical, with sounds emanating from characters as though speaking with a talk box or instrumental sample. Every conversation harmonizes with the jazzy pulse of the soundtrack, with each click through the dialogue contributing to the beat.

Cosmo D once spoke to me about the New York club scene in the late 2000s as a similarly precarious moment amidst nightly partying, in which artists on the verge of global stardom and business interests, ready to corporatize a brewing subculture, revamped entire neighborhoods and careers. The Norwood Suite might envision a fanciful locale conjured seemingly from a post-party dream, but its concerns are entirely grounded in the here and now.

Miguel Penabella is a PhD student investigating slow media and game spaces. He is an editor and columnist for Haywire Magazine. His writing has been featured in Kill Screen, Playboy, Waypoint, and Unwinnable, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.