Storyplay: Care in the Face of Horror

Melody remembers to water the plants.

I played Lone Survivor when it first came out in 2012. I didn’t understand too much of the plot at the time, and after completing it I decided to move on to another game instead of trying new game plus. But the game got under my skin and unsettled me more than I cared to admit. I wasn’t scared by the monsters, the tension, the creepy music, or the darkness. It was precisely that I wasn’t understanding it, and the game knew it and confronted me about it.

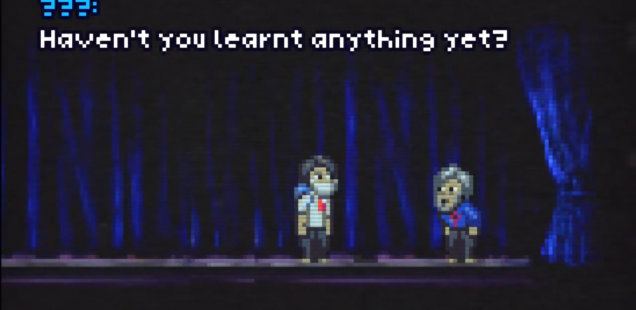

There is a scene right at the end of the game that I would later learn is part of the “blue ending,” the one people are most likely to get on their first playthrough. In it, the protagonist loses his temper and shoots a man only named “???” The man stands there for a while, blood pouring down his blue shirt, then suddenly screams, “Haven’t you learnt anything yet? You’ll have to do better than that!” I was stunned. I didn’t even know the game wanted me to learn something. What did I do wrong? Why was the game yelling at me, blaming me, making me feel so inadequate? It was begging me to replay the whole thing with more attention and care, but I just didn’t have the strength to go back to it. I wasn’t quite ready.

Only recently I found the courage (and the time) to explore it again. And with it I also picked up Claire, a game from 2014 whose feel and look all but mimic those of Lone Survivor. Unfortunately, for me Claire is quite clearly the weaker game, and the experience didn’t resonate with me half as much as playing Lone Survivor. Nonetheless, playing Claire in the shadow of Lone Survivor made me aware of both games’ focus on the ethics of caring for oneself and others.

Claire is a very predictable game; people who have experience with similar games will immediately and intuitively understand how its underlying systems work. Your inventory screen shows you a description of your health status, as well as a description of your emotional state: calm, unsettled, terrified, etc. You lose health when enemies hit you; your mental health deteriorates when you witness scary or unsettling things, and conversely it improves when you spend time in well-lit areas without monsters. The items are almost always described by two sentences: one is flavor text, and the other explains what stats the item affects. A cola gets you some health back, a cup of tea restores some health and calms you down, and caffeine pills restore health but make you feel more tense.

These are the kind of abstractions and simplifications borrowed from the RPG tradition that we have come to expect from most videogames. And it’s not that using them is wrong – pretty much every game functions using stats, flags, or similar methods, due to the very nature of coding – but in almost every case, this mechanical reduction of complex real-life processes hampers games’ emotional resonance. The player is encouraged to think about system manipulation and what the best or most efficient outcome might be, often to the detriment of empathy and immersion in the narrative and the atmosphere. Using a word as opposed to a number to describe the protagonist’s inner life is already a small way to humanize it, but Claire overwhelmingly and explicitly relies on its mechanical systems, making it a worse narrative experience.

Claire‘s idea of self-care amounts to little more than “don’t die,” which the player will try to avoid anyway in service of completing the game. The game is an inner journey: Claire has attempted suicide after a tragic and traumatic childhood and adolescence, and she is struggling between life and death. The way she behaves during the course of the entire game determines if and how she lives or dies. However, we’re not asked to care for Claire’s wellbeing outside of managing the two stats of health and emotional wellness.

The game explores caring for others in a simple way, but one that’s more interesting than caring for Claire herself. If Claire carefully explores the labyrinthine spaces where the game takes place, she will meet a few different people who usually have a problem and request her help. The player can decide to go out of their way and help them, or simply forget about them and move on.

The game makes it obvious that the problems these people have are also Claire’s own problems and that by helping them she is actually helping herself. After all, these people are not real, but Claire’s own projections. Helping Elle, the woman with Alzheimer’s disease who lost a locket with a picture of her family, is really about helping Claire remember, confront, and accept her past. When Claire meets the librarian, she mentions how she is envious of her dedication to her books, because she cannot find a passion of her own, something to dedicate her energies to. Presumably, helping the librarian recover the books that were never returned is a way for Claire to work through that.

In the game’s view, generosity and compassion towards others turn into generosity and compassion towards oneself. In the final scenes, the people Claire has chosen to help reappear to comfort her and cheer her on. Help enough people and Claire will wake up, although the details vary from ending to ending. It’s not a particularly innovative idea, and there is a degree of selfishness involved, but it’s an effective mechanic that doesn’t completely trivialize its own subject matter like the “out of sight, out of mind” handling of stress. Through these mechanics, Claire is trying to find an effective way of delivering the emotional content of its plot.

The first time through Lone Survivor, it’s likely the player will run around killing as many monsters as they have ammo to. In fact, the game subtly encourages this: when the survivor first obtains his gun, he goes back to a room where two of his friends were dancing. He finds them dead, with two zombies standing over their bodies. This is the only time when the game automatically takes out the gun and enters aim mode. Understandably, the player shoots, but they don’t have to. Holstering the gun and walking away has to be a thoughtful, deliberate decision.

A pacifist run in Lone Survivor is never moralized in the standard way: the game doesn’t pull a banal bait and switch, suddenly revealing that the zombies were really people just like you. Instead, its argument against violence is more radical and universal. It doesn’t matter whether zombies are people or not, violence takes a toll on the one carrying it out, regardless of the identity of the victims or the aggressor’s justifications. Of course, violence is always the easier, more convenient solution: for one, if you kill the enemies you don’t have to sneak past them multiple times. The drawbacks— the damage to the survivor’s mental health — are invisible, and only come to the surface in the long run.

When it comes to violence, Lone Survivor is actually quite explicit, if the player is willing to listen and take seriously what is written on the notes and diary pages found at the beginning of the game. A couple of them explicitly encourage finding nonviolent solutions, while a few others, written by a man named Draco, praise violence as a necessity but come off as the musings of a psychopath. But it’s not just about nonviolence. Refusing violence is part of a bigger and surprisingly detailed picture of self-care.

Like Claire, Lone Survivor is the story of a man trying to find a way of dealing with his traumatic experiences. The ending the player reaches depends purely on the mental health of the survivor. There is no meter for it, no way to check its status when playing, and no real feedback. The survivor will complain when he’s tired or hungry, but he will not comment on what makes him feel better or worse. Only at the very end of the game do we get a psych report evaluating the character’s mental health, together with a list of contributing factors.

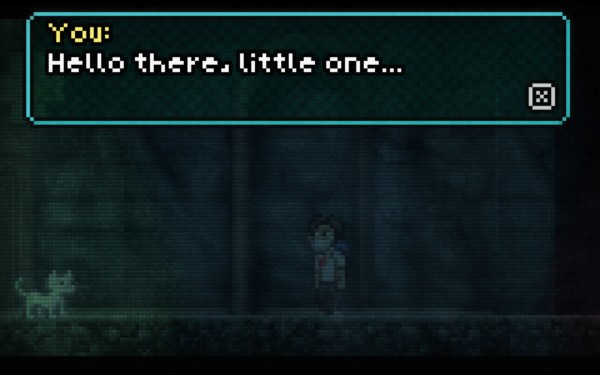

To get the best ending, the player has to take care of their character in very deliberate and careful ways, aside from not killing. The survivor benefits from regular sleep, not too much and not too little. He benefits from eating good food and taking the time to cook it, and from drinking water regularly. Watering the plant and adopting a stray cat also help, as does making some time to relax, play a game, or listen to music. A cup of coffee a day is good for you, but two can be detrimental, as can be abusing your pills.

I know no other game, even among those that focus on stress and mental health issues, that has such an elaborate system in place, save perhaps for Darkest Dungeon, which privileges gameplay over narrative anyway. I never thought it would make a difference if I ate a slice of cheese instead of ham and beans. Maybe the latter would stave off hunger for longer, but I didn’t consider if the survivor might like it more.

Taking care of others also improves the lone survivor‘s mental health, but not quite in the same way as in Claire. Taking care of others doesn’t simply amount to fulfilling their requests, but rather listening to them, thinking about them, and sometimes doing what is best for them, not just what they ask you to do. For instance, you meet Hank in the second half of the game. He says he’s been bitten by a zombie and will soon become one of them. He mentions being out of supplies and asks you to give him some of your pills in exchange for ammo. Your pills are psychoactive drugs, not a cure for turning into a zombie: in short, he wants to get high. You can give him the pills, but you can also give him one of your precious health tonics instead, after which he will mention feeling a lot better.

Giving him health tonics is not a choice that the game explicitly offers you. It is possible to “give” most objects, both helpful and detrimental, so it’s really just something that has to come out of the player’s empathy, compassion, and the thin hope that it might just work. You can also cheer him up by giving him your cat plush.

By far the biggest achievement of this entire system is that it is immediately understandable and easy to relate to, so much so that we don’t need much feedback to make the right decisions. If anything, the psych report is almost necessary because players wouldn’t otherwise know that such a system is even in place, so used are we to characters who remain unaffected by the events unfolding in front of them. But once you know the system is there, the way it works is transparent. Lone Survivor successfully hides its stats under a believable narrative, to the point that we don’t think of stats anymore, we simply try to take care of our character as best we can. It encourages empathy, not system-driven thinking aimed at efficiency. The story, the atmosphere, and the emotional impact of the game all benefit from this veil shrouding the cogs that make it function.

Reach the end with good-enough mental health, and the survivor will be ready to confront the truth of his trauma and start working to overcome it. Now I understand why the game was yelling at me, and why I couldn’t bear to replay it. I really wasn’t taking good care of myself back then, and I wasn’t ready to listen.

Claire and Lone Survivor are both narrative-focused games trying to find the most powerful and effective mechanics and systems to pair with their stories. However, the way Claire asks the player to care for Claire herself doesn’t really promote nurturing on the side of the player. When other people are involved, the system ultimately falls short of capturing the essence, posture, and attitude of caring for others. Instead, the act becomes mechanical, simply a matter of following orders, no different from completing a quest in any RPG except that the reward for it comes in the form of a better ending instead of money or experience points.

Ostensibly, Lone Survivor looks no different: complete the game with better mental health in order to receive a better ending. But the way it models every interaction surrounding care makes all the difference. It’s not only that it results in a more effective telling; it is an integral part of the story being told. Discovering the importance of self-care; realizing how it passes through many actions, big and small, including openness, receptivity, and compassion towards others; and practicing it deliberately and with patience over the course of the entire game— this learning process is something that the player needs to experience and act out together with the titular survivor. Aside from the details of the lore, Lone Survivor is simply a story about learning to take care of oneself without giving in to the surrounding horror. This story cannot be told without the participation of the player — not in the mundane sense of a person pressing the correct keys on the keyboard until the game is completed, but a player who is personally involved in the emotional development of the narrative and starts acting differently as a result of what they learn during their time with the game. Lone Survivor is one of those rare works that truly makes use of its unique form as a videogame to tell a story that goes beyond mere plot, and that it couldn’t tell in any other medium.

Melody is passionate about games, words, and music, and she expresses her love by meowing. You can find her on her blog, and on Twitter.