Opened World: The Hollow Spectacle of Power

Miguel Penabella praises meaningful choices that don’t matter.

Wolfenstein: The New Order depicts a frightening, globally devastating alternate history of continued Nazi power throughout the mid-twentieth century, with hordes of mechanical beasts and legions of soldiers who have taken over the world after the Allied defeat of World War II. Gunfights are fierce and explosive, conveying the raw power of your fascist adversary. But one comparatively quiet scene communicates the power of the Nazis even more sinisterly and memorably than any action sequence in the game. In a brief conversation during a quiet train ride, Wolfenstein delivers a moment of tightly staged drama, where the choices you make have unclear consequences, heightening our sense of powerlessness against the Nazi regime. For a game made popular for its fast-paced power fantasy of killing Nazis, The New Order unspools its most compelling commentary on fascism, spectacle, and power by revoking our agency. It achieves this through a hushed conversation with antagonist companions who toy with our fears in their own game whose rules are too opaque to understand.

The scene begins with protagonist William J. Blazkowicz hiding in plain sight on a night train to Berlin, concealing his identity as part of the underground resistance movement. Sneaking some midnight coffee from the dining car, Blazkowicz encounters a Nazi patrol with four humans, and one colossal steel robot. Two individuals are members of the high command: Obergruppenführer Irene Engel and her companion, Bubi. Before the player can lead Blazkowicz to the exit, Engel calls out for him to set the coffee down on her table. Attempt to leave, and the guards block the path. Approach the table, and Engel grabs Blazkowicz’s arm and looks directly into the camera, staring into our first-person point-of-view at Blazkowicz, and by extension, at the player. She notes his “very nice Aryan features,” and Blazkowicz does indeed fit the bodily ideal of the Nazi regime as a cisgender white man, with a muscular physique, blond hair, and blue eyes. But he is also Jewish, and a central figure to the resistance. Whether or not Engel knows this latter fact is unknown to us, and thus, her intentions remain hidden. Waving a golden pistol, she commands Blazkowicz to sit opposite her and Bubi. She proposes a test for Blazkowicz, a psychological association game “designed to determine if there are traces of impure blood running through a person’s veins.” Because she has already noted the protagonist’s Aryan features, she expects him to pass the test “with flying colors.” Her confidence adds an extra level of risk for the player, as you must meet her expectations and answer every question correctly, lest Blazkowicz be outed as a fraud and a spy.

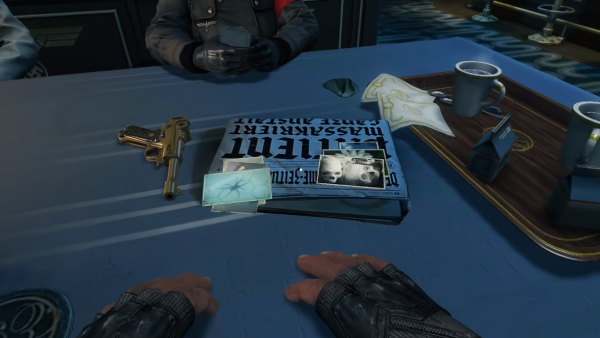

Voiced by actress Nina Franoszek, Engel radiates a sinister playfulness as she threatens to shoot Blazkowicz before laughing it off as “just a test!” The sheer spectacle of Nazi weaponry on display suggests otherwise; it’s not just a test, but a demonstration of fascist power. Seated at the table, our visual frame remains limited. Engel and Bubi sit opposite the player in the foreground, while a hulking mechanized robot idles in the middleground. Two Nazi troopers guard either side of the train car, with one armed guard visible in the background, while the other is stationed offscreen behind our field of view. This visual framing reinforces the idea that we’re being held captive despite the friendly façade Engel adopts. Both she and Bubi maintain direct eye contact at all times, studying Blazkowicz with intense, unnerving scrutiny and never averting their gaze. Placing the pistol at the center of the table, Engel explains the rules of the game, laying two photographs at a time next to the gun. Players must first choose which image makes them excited, then happy, and finally, disgusted. The images presented are emptied of context, featuring a close-up of an eye, a flower, a smiling mouth, etc. In contrast to the action sequences that largely comprise this game, your ability to interact is limited. Players can only move their head to look around or make a selection from the objects in front of them. Decide not to respond, and the antagonists snicker, goading you to choose. Accepting their deadly game remains the only way to escape.

While Engel presents two photographs at a time from which to choose, there are really three choices available: either one of the two photos, but also the gun, conspicuously positioned between Blazckowicz and the antagonists. Moving the reticle over any of those three objects, causes the game to light up a prompt to confirm the final decision. Choosing any of the photos results in an inscrutable, poker-faced response from Engel as she casually remarks, “Well, well” or “Interesting.” Even just looking at the gun seems to pose incredible danger, as Engel anticipates your thinking and warns Blazkowicz that he’ll be dead if he picks up the pistol. The choice feels like a false hope of escape, as one measly pistol surely cannot outgun multiple armed Nazis and their massive robot sentry. And yet the gun remains a tantalizing choice throughout this sequence.

Right before the final choice, however, Engel calls out to the guard Bernhard to ask if he thinks Blazkowicz of impure blood. The moment abruptly moves us out of the suspenseful microcosm of the game in the dining booth and reminds us of the greater danger that exists outside it. Her gesture backwards subtly prompts us to direct the camera from the objects on the table to the back of the train, and our gaze falls upon the weaponry of the sentry and the armed guard. This moment marks the turning point of the sequence. Prior to it, no music plays during the scene, leaving only the quiet of dialogue and the gentle sounds of the train speeding through a rainstorm outside. Engel draws the final two photos of a spider and a pile of skulls, tense music swells as the stakes rise. Make a selection, and a scripted sequence plays out where Engel grabs Blazkowicz’s hand only to warn that this is “the final card,” initially fooling us into thinking that we guessed incorrectly. Her warning prompts us to overthink our choice as we attempt to read her mind and intimate what the images could possibly mean. Her confirmation that this is the final set of photos also reintroduces the pistol as a viable choice, as perhaps the last moment to gamble on that chance.

Attempt to reach for the weapon on the table, and the shrill cry of the Nazi robot rings out as though emerging from a nightmare. The screen blurs as the sentry guns Blazkowicz down, and the red eye of the machine looms like an encroaching monster, advancing forward as he crawls futilely away. The way to survive the game is to refrain from reaching for the gun and select a photo instead. Upon doing so, Engel brandishes the pistol, confessing, “If you had not been an Aryan, you would have gone for the gun.” Thus, she reveals that the entire test serves as a trap. The photos are meaningless, “vacation pictures, old war photos. Nothing more,” admits Engel, laughing it off. Regardless of which photos are chosen throughout the test, the outcome will always be favorable; only upon reaching for the gun does Blazkowicz fail. This revelation reflects the emptiness at the core of their ethnofascism, as their test is not backed by any kind of logic or meaning, and any choice in photographs will all lead to the same aftermath. All that undergirds their racist belief system is a theatrics of power. Their charade only succeeds because it’s made consequential by the presence of a handgun pointed at Blazkowicz and the heavy weapons that target him if he deviates from their game. The test is merely a pretense to kill; by design, it wants to define any who play it as “impure.” But any test for “impure blood” is impossible; who lives and who dies will always be up to Engel, who can choose to kill anyone at any time. Fascism is reinforced by power structures that disguise it as ideology, and by the spectacle of domination and violence, here visualized in the giant robotic weapon that lingers always in sight of the player. Elsewhere, the massive steel and concrete cities of the Nazi regime overwhelm the senses and convey the grandeur of state power. Such examples represent grotesque spectacles that call attention to the emptiness at the core of the racist Nazi belief system.

“I can spot an impure with my naked eye,” Engel tells Blazkowicz as he leaves, but this too is a lie, because she fails to detect him as a Jew and a saboteur on their train ride to Berlin, and later again when she and Bubi fail to immediately identify him when they reappear at Camp Belica. These moments reinforce the inherent meaninglessness of their logic, and upon their failure to detect Blazkowicz as their enemy, their entire charade crumbles. While certain displays of power like their weaponized mechanical behemoths or their colossal cities of concrete serve to subjugate the populace under the fascist heel, these things can ultimately be detonated from underneath by a resistance. Here, in this train car, the hollow frameworks of Nazi power are exposed, later to be dismantled and destroyed.

Miguel Penabella is a PhD student investigating slow media and game spaces. He is an editor and columnist for Haywire Magazine. His writing has been featured in Kill Screen, Playboy, Waypoint, and Unwinnable, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.