Opened World: Shattered Memories

Miguel Penabella revisits an old story.

A moment is sometimes all that it takes for ordinary life to slide effortlessly into the dreamlike. Lost in thought, our minds may wander to a memory of another time and place, before snapping back into focus, having recovered some newfound insight or emotion conjured up from momentary reverie. This is the central conceit of Sam Barlow’s 1999 game Aisle, a one-move text adventure game that tasks players with typing a single command for an unnamed protagonist at a grocery store. As the instructions that introduce the game announce, “Your intervention will begin and end the story,” thus signaling to players that we will only access a small snapshot of a much longer, richer life.

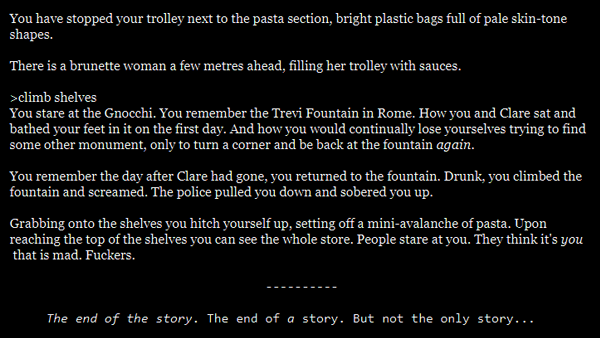

The narrative setup is strikingly ordinary: a man concluding a hard day with grocery shopping momentarily reminisces about Rome upon encountering a package of gnocchi, and then turns to see a brunette woman down the aisle. Players accustomed to interactive fiction may link Aisle to foundational predecessors like Zork or Colossal Cave Adventure, but Barlow upends generic conventions entirely. Aisle does not build towards some kind of victorious future of acquiring treasure or escaping dungeons, but instead reaches backwards into the past, text commands like “Buy gnocchi,” “Look at woman,” or “Examine pasta” triggering memories revealing of character. The short length of the game encourages multiple resets, as players can build a more complete profile of the protagonist by experimenting with different commands and closely reading the text for new possible narrative strands to uncover. As many possible backstories slowly reveal themselves, any singular truth remains elusive, resulting in a complex character study that explores the unstable, slippery quality of memory.

Aisle rewards plentiful backreading akin to detective work, in which players must construct an obscured backstory from snatches of textual clues embedded in half-recalled memories. In Aisle, narration is presented with the second-person pronoun “You,” linking the protagonist with the player and granting us—in bolded text—brief entrance into his inner thoughts: “Interesting… fresh Gnocchi–you haven’t had any of that since… Rome.” This is the first major clue that intimates a world beyond the grocery store. Linking the word “Rome” with a command, such as “Remember Rome” or “Ask woman about Rome,” yields further clues that lead down narrative paths that paint the protagonist as a wistful, even tragic, figure. Mischievous players may be tempted to experiment with sillier commands, like “Get in shopping cart” or “Dance,” but the game’s multiple endings ultimately loop back to one of a handful of thematic motifs, hinting at some kind of emotionally fraught memory of Italy involving a woman named Clare. Throwaway commands seemingly irrelevant or silly become charged with emotion given Sam Barlow’s prose. The frivolous command “Jump,” for instance, doesn’t result in the protagonist jumping up in the air. Instead, the command triggers a memory of the past, transporting us out of the space of the grocery store and into Italy, where fragmented details of a scene—a split-second decision, a bright flash of red, a momentary lapse in time—startle the protagonist out of his flashback, suggesting some kind of repressed trauma. Crucially, the game never provides the whole story, preferring impressionistic sketches of the past with each command, as though these memories are either too far away to remember in detail or willfully forgotten to erase some prior hurt.

Each command attempted builds player knowledge of what associations and images spark the protagonist’s neuroses or yearnings, as key details attain totemic significance in their repetition. The command “Wait,” another seemingly innocuous instruction, transports players again to Italy, conjuring up an allusive, urgent portrait of romance. Eschewing any concrete information about the protagonist’s relationship with Clare, Barlow instead focuses on sensual details of a hot metro station and the tactile sensation of a hand’s touch. Memories of Clare in Rome clearly haunt the protagonist, but these backstories shape an incomplete understanding of what transpired. As details slowly fill in gaps in knowledge, players may turn to commands that compel contemplation. “Remember Clare” seems to confirm a romantic holiday with Clare but insinuates that “something happened” that led to Clare’s present absence. This ambivalence towards granting the full truth reflects the game’s metafictional interest in expanding the parameters of adventure game mechanics. In a conventional text adventure, the action of inspecting an object often results in a perfunctory description that serves utilitarian purposes, clarifying the direct use of the object for the player. Here, objects aren’t inventoried for later use; they instead serve as vessels for emotion and memory. “Examine gnocchi” invites players to share in the heartache of lost love, as the protagonist associates the food with warm memories of a candlelit dinner and Clare’s illuminated, loving presence. Bringing up the inventory reveals a treasured photograph, which isn’t deployed for any purpose but is simply allowed to exist, adding to the protagonist’s sense of quiet devotion.

Complicating the narrative, however, are the many possible endings that present contradictions, inconsistencies, and mismatched timelines that prevent a singular reading of what transpired with Clare. The game’s opening prompt warns players of these narrative discrepancies, contending, “You will be asked to define the story… Not all of the stories are about the same man.” Thus, repeated plays conceptualize many different versions of the protagonist and Clare, where a memory may recall an accident, a new boyfriend, an illness, a suicide, or even a murder as one of many possibilities that accounts for her present absence. These many iterations of truth cast the events of the game in a surreal liminal zone, where backstories register not as reality, but as a kind of illusory space of desire. If players believe Clare to have died in Rome, then a subsequent garden path in which the brunette woman at the grocery store is revealed to be Clare may read as a melancholic, fantastical wish fulfillment. The game’s indifference to offering a stable truth suggests the protagonist’s own inability to come to grips with some undefined emotional unease, where an understanding of some recent event in the past remains in flux. The role of the player in inputting a command allows the character to move out of his solipsistic mire and express his grievances through language, moving closer to some kind of release beyond the boundaries of the game.

Aisle may be twenty years old, but its approach to interactive fiction feels vital. Its deployment of player commands to shape character backstories and an impressionistic feel for the past anticipates the oblique prose of Kentucky Route Zero. Aisle’s narrative structure also lays the foundation for later games Sam Barlow would design and write, where differing responses to a therapist alter our perception of the world in Silent Hill: Shattered Memories and incomplete testimonies of the past must be pieced together to form a comprehensible alibi in Her Story. Aisle, Shattered Memories, and Her Story all share a thematic interest in tasking the player with defining the story through piecemeal impressions of truth, and in Aisle, the protagonist is stuck at a kind of crossroads moment in his life, where we can either decide to let him dwell on the past or make steps towards future catharsis. My favorite ending, “Call Clare,” is one of a few happier endings buried among so many other bittersweet or tragic tales. In it, the protagonist simply calls out Clare’s name, and she appears, stepping into the aisle as though all those insinuations of an accident or breakup were nothing but anxious fantasies. The ending is startling in its simplicity. It’s not an ending that feels real, but it feels right nonetheless.

This and the title image come from Netflix’s The Sinner, a show that doesn’t have very much to do with grocery stores.

Miguel Penabella is a PhD student investigating slow media and game spaces. He is an editor and columnist for Haywire Magazine. His writing has been featured in Kill Screen, Playboy, Waypoint, and Unwinnable, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.