Opened World: On the Margins of History

Miguel Penabella takes a page from the past.

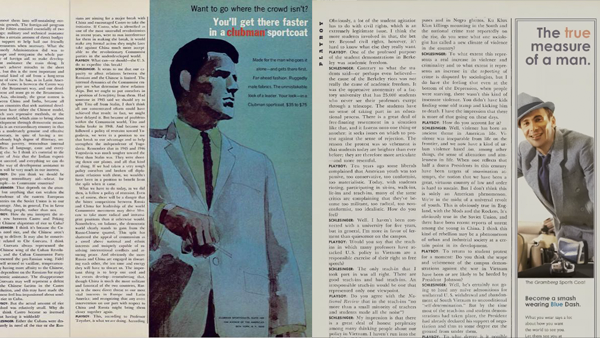

Dispersed throughout the muggy bayou locale of Mafia III are various Playboy magazines befitting the game’s late 1960s setting. These collectibles can be viewed for the player’s pleasure, incorporating scanned covers and nude centerfolds from the real-world magazine, and sometimes also including selected articles and interviews within the issue. Those familiar with these old magazines’ surprisingly erudite written content may recall the sprawling interview between Alex Haley and Martin Luther King Jr. or short fiction by Joyce Carol Oates and David Foster Wallace. As a casual collector of vintage Playboy magazines, what I find significant in this seemingly trivial side of the game is what it rewrites on the margin. Taking Mafia III’s scan of the May 1966 issue as an example, we’re treated to a long-form interview with historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. by Alvin Toffler. Those familiar with these old magazines know how riddled they are with advertising, but on the margins of this interview, developer Hangar 13 removes the original images and replaces them with fictional ads for “Blue Suit” and “Bon Temps” brands of beer instead of the original Budweiser, as well as a “Gramberg” sports coat over the original Clubman. The game imitates the aesthetic of 1960’s advertising with long copy underneath the image, privileging the surface look and sheen of the time period alongside attractive nudes.

Of course, obvious problems with brand licensing prevent Mafia III from depicting the true magazine prints, but the erasure and rewriting that we’re left with remains noteworthy nonetheless. The game wants to portray history with a real-world cultural artifact but at the same time distorts the full picture. Beyond the collectible magazine scans, Mafia III similarly conducts a far broader process of historical erasure and rewriting in the story and setting itself, simplifying the realities of marginalized peoples in the turbulent period of civil rights in the 1960’s American South. Set in 1968, the game follows Lincoln Clay, a biracial war veteran having just returned from service in Vietnam only to be betrayed and left for dead by the Italian mafia because of his connections with the now dismantled black mob. Over the course of the game, he slowly usurps control over the city district by district from the Italian and Dixie mafia and eliminates those who wronged him. Mafia III, like the Grand Theft Auto games the series is frequently compared to, provides a fictional setting cloaked in real-world historical and cultural contexts. By fictionalizing its setting and some of its historical contexts via placeholder names and allegorical proxy, the game abstracts and conceals crucial information that severely undermines its overall political commentary.

Mafia III interweaves real-world cultural anchors like Playboy magazine and a soundtrack from the likes of Creedence Clearwater Revival and The Supremes, but it softens its historical mimesis with a lack of specificity elsewhere. The game takes place not in the polyglot, Creole seaport of New Orleans but in New Bordeaux. Lincoln encounters not the white supremacy of the Ku Klux Klan, but the Southern Union. This distanciation from historical specificities dulls any attempt to sharply critique the realities of racial discrimination and violence. What the game offers is not a precise comment on civil rights in the 1960’s, but “guilt-free context for some contemporary catharsis” as pointed out in the great review by David Chandler for Kill Screen. Mafia III’s indecision by mediating fact with fiction is why I take issue with Ed Smith, Patrick Lindsey, and Reid McCarter’s takes on the game for Bullet Points. They praise its gratifying brutality as gesturing towards a general, contemporary anger against institutionalized racism akin to violent Blaxploitation films, but in doing so severely overlook issues of authorship and artistic marginalization.

(Original ad on the left, Mafia III‘s recreation on the right. -ed.)

If we are to read Mafia III as a Blaxploitation videogame, then we understand the game as centralizing a story of urban, African American characters steeped in generic crime tropes that toe the line between black empowerment and gross stereotyping. Mafia III confronts painful racial injustices through the experiences of the mobster Lincoln, but it situates these aggressions ahistorically when viewed in hindsight through the lens of current black activism and racial discourses. The political rigor of Blaxploitation movies stems from their historical contexts; many seminal works within the genre were in dialogue with civil rights organizations like the NAACP regardless of these films’ effectiveness in advancing the cause of black empowerment. Moreover, several of these films were directed by filmmakers engaged in civil rights activism like Gordon Parks (Shaft) or Ivan Dixon (Trouble Man), the former having previously conducted photojournalistic work documenting militant political figures like Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael. Conversely, the leadership of the Mafia III development team is largely white—director Haden Blackman and lead writer Bill Harms, for instance—save for the black senior writer Charles Webb, whose interview with Austin Walker for Vice provides more valuable insight on race relations and representation than the game itself. While not necessarily essential to craft a fair examination of race in the United States, the presence of black perspectives behind the scenes can open room for cultural and racial nuances that may otherwise be lost, especially when the story’s primary themes revolve around how people of color are discriminated against in everyday situations.

The game’s frequent claims to realism serve as stumbling blocks that muddle its message. An opening disclaimer by the developer asserts, “We sought to create an authentic and immersive experience that captures this very turbulent time and place, including depictions of racism,” yet the game shies away from the aforesaid specificities of place and historical context. Mafia III’s frame story, conveyed in flashback through the lens of a documentary, suggests that the entire game is filtered through the unreliability of memory and myth, yet simultaneously employs slideshows of actual period photographs and newsreel footage as though to allege the grounded reality of these events. The game suggests that Lincoln Clay essentially undergoes the same cultural and historical developments as other black Americans in the 1960s, surrounded by the music of Sam Cooke and amidst the public grieving over the death of Martin Luther King Jr. Nevertheless, this notion remains a falsity; New Bordeaux exists in a fictional bubble outside the true contexts of Birmingham or Selma, and far from the legacy of slave revolts in New Orleans like the 1811 German Coast Uprising or white supremacy outrage following the New Orleans school desegregation crisis of 1960. Mafia III occupies the realm of fantasy, erasing certain elements of history and diluting the complex processes of time.

We can witness Mafia III’s shortcomings by identifying where the game directs its racially motivated anger and how it depicts black militancy. Historian Bob Whitaker for History Respawned offers an informative background of New Orleans during the 1960s drawing from the work of fellow academic Leonard Moore from the University of Texas at Austin, and though Whitaker ultimately grants that the game is an “instructive facsimile,” he also notes its historical flaws. By working through Moore’s book Black Rage in New Orleans, Whitaker acknowledges that the police department perpetuated segregation and racial violence in Louisiana, lawfully conducting policies of white supremacy in lieu of the Klan. Whitaker also notes that Lincoln’s positive experience serving in the military and his close friendship with the white veteran and CIA agent John Donovan is uncommon relative to the real-life experiences of black servicemen. Here, this relationship serves as narrative shorthand to streamline Lincoln’s access to insider information on the mafia, with Donovan acting as a vessel for exposition.

Thus, the game expresses racial anger obliquely, directing it not towards real structures that lawfully maintain oppression like the police force, but towards fictional abstractions like the Southern Union and the Italian mafia. Rather than confront the historical sources of oppression in New Orleans as outlined by Whitaker and Moore, Mafia III defers to fictionalization that obscures the relationship between racism and state politics. Furthermore, since police during this period preserved racial order via homicide, assault, and verbal extortion, Lincoln’s similar actions throughout the game only serve to mimic entrenched oppressions. The game attempts to portray black nationalism in the form of The Voice, a militant running a guerrilla radio station again shied away from direct association with its real-world parallel, the Black Panther Party. Mafia III emphasizes the militant aspects of black revolutionary movements rather than the Black Panther Party’s involvement in community service to feed the hungry and provide health clinics to underserved, marginalized neighborhoods. Flores Forbes, a member of the Black Panthers, notes, “the public wanted to believe that we were just thugs with leather jackets and guns,” and Mafia III unfortunately perpetuates those same myths of black militancy even in its very cover art.

Mafia III does occasionally succeed in allegorizing racial discrimination through oppressive gameplay mechanics, but its overall design misconstrues the difficult, marginalized histories of the 1960s. Shop owners act belligerent upon Lincoln’s entry in a segregated “No Colored Allowed” building and will call the police after a time. Players are labeled “Trespassing,” the same warning when stepping foot in enemy territory, thus marking mundane spaces like a gas station or restaurant as potentially hostile and antagonistic to non-white demographics. Like Assassin’s Creed III: Liberation, different neighborhoods are policed differently along racial lines: primarily black districts like Delray Hollow are laxly guarded while the wealthier white areas of Downtown and the French Ward are strictly protected. But despite the institutionalized Jim Crow laws that enforce racial segregation, Mafia III ultimately portrays Lincoln Clay quickly ascending through the ranks and amassing considerable wealth in spite of the bleaker realities of 1960’s race relations. The unimpeded triumph of black subjectivity amidst racialized violence proves to be a power fantasy, and all the game can do is simply relegate Lincoln within the same capitalist system of institutionalized oppression. He earns money and topples the mafia but remains separated from political engagement. By turning black organization into a business, Lincoln Clay evades Huey P. Newton’s proclamation that “We must destroy both racism and capitalism.” By conducting a process of vengeance without heed to constructive grassroots actions for his own community, he disavows Bobby Seale’s admission that “Revolution is not about shootouts.” Lincoln is rewarded for being part of the same power structure of his oppressors, reducing success to one’s ability to simply make money. Rather than a fundamental destabilization of power, the same structures are maintained under the guise of completing the overall campaign.

In abstracting the 1960’s American South and lacking a revolutionary disruption of power relations, any political and racial commentary in Mafia III collapses for fear of being direct. Far from being cuttingly politicized or even cathartic, the game falls into the tedium of open-world distraction, becoming rote work rather than a worthwhile polemic against institutions. The game may encourage empathy for its black characters, but the realities of race in the United States today (especially after a disastrous election marking the rise of global fascism and white supremacy under the guise of the alt-right) demand more than empty power fantasy to undercut political oppression. In a broader cultural landscape populated with nuanced art by black authors like the album A Seat at the Table by Solange or Freetown Sound by Blood Orange, movies like Moonlight by Barry Jenkins or 13th by Ava DuVernay, television shows like Atlanta by Donald Glover or Insecure by Issa Rae and Larry Wilmore, or literature like Swing Time by Zadie Smith (all released this year alone!), major videogame released this year have struggled to produce works with comparable richness in theme and authenticity. That there seems to be no widespread dismay amongst games culture for failing to supply a distinct perspective on blackness in such a crucial moment in politics is cause for concern. The simple solution is to take a harder look at the world and speak—generously, truthfully—and produce a meaningful statement, loud and clear, directly and in plain sight.

Miguel Penabella is a freelancer and comparative literature academic who worships at the temple of cinema but occasionally bears libations to videogames. His written offerings can be found on PopMatters, First Person Scholar, and Unwinnable, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.