Opened World: Finding Her

Miguel Penabella travels the world with Carmen Sandiego.

Like many, I owe my introduction to videogames to a group of savvy women with aspirations for the then-underexplored field of educational games. As Abigail Cain wonderfully details in her history of The Learning Company, developers Ann McCormick, Teri Perl, and Leslie Grimm, together with Warren Robinett of Adventure fame, formed the company in 1980 with funding from the National Science Foundation and the National Institute of Education. The three women all held doctorate degrees, and they launched the company with Robinett in the hopes of advancing personal computing as an educational tool. Alongside successful entries like the Reader Rabbit and ClueFinders series, The Learning Company later published Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? after Brøderbund Software’s initial release of the game in 1985. Brøderbund founders Gary and Doug Carlston were inspired to develop the trivia-like game based on their childhood habit of quizzing each other facts from the almanac. Together with their sister Cathy Carlston, who was essential to educational outreach that made the game a household name despite sexist trades press that downplayed her role, the siblings aggressively promoted Carmen Sandiego as a teaching tool for schools. But what exactly are the lessons to be learned from such educational games as Carmen Sandiego?

Looking closely, three important lessons emerge. For most young children, educational games are often the first encounter they have with videogames, and thus, games like Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? teach children, at the most basic level, how to interact with game software. Long before I ever even touched a console game, the simplified menu-based input of educational games was my entrance into the culture. Games like Carmen Sandiego simplify the experience of an adventure game, swapping text-based input like that of Colossal Cave Adventure for menu-based commands to facilitate the gaming experience for much younger audiences with a more limited vocabulary skillset. Seeking to develop these skills further, Carmen Sandiego also instructs children how to interact with reference books and apply their knowledge to solve problems. As the game was originally packaged with a physical copy of The World Almanac and Book of Facts, its gameplay extended beyond the screen and into the material world of reference books. Finally, the game’s ultimate message is the value and fun in cultivating a greater sense of worldliness. While children’s experiences and reception to the game will differ, Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? merits some credit for introducing elementary school children to places like Port Moresby or Reykjavík in ways that encourage greater curiosity for a world outside their own. By teaching basic facts about the world and encouraging children to seek out deeper knowledge with an almanac, Carmen Sandiego promotes worldly curiosity and independent learning both within and outside the game.

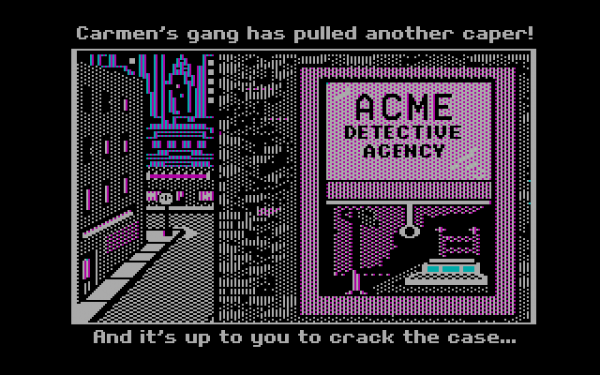

The game tasks players as detectives for the ACME Detective Agency to investigate the heists of Carmen Sandiego and her legion of cronies as they flee across continents, and a repertoire of cultural knowledge becomes key to outsmarting the eponymous globetrotter. Players travel from city to city, gathering clues that players can use to infer which city the suspect is likely headed to next. As the investigation progresses, players slowly build a criminal profile from snippets of witness testimony to narrow down a pool of suspects until one can be intercepted with a warrant. For example, one witness may provide information that the suspect fled on a plane “with a sun flag on its wing,” and additional clues indicate that the suspect was looking for “Spanish colonial maps” and was planning to “fly a glider over the Gran Chaco plain.” Keen players, consulting their handy almanac, can thus safely assume that the suspect has fled to Buenos Aires, Argentina. This gameplay structure of clicking through dialogue to amass clues, jetting from continent to continent to find further information, and inputting acquired evidence to the Interpol archive anticipates the hypertext interaction of the Internet to come. Playing the game is essentially navigating a digital database, in which players obtain information from a pool of sources and apply this knowledge to effectively continue their research down the appropriate path. Flying to Singapore instead of Buenos Aires would lead to a dead end in research, requiring players to backtrack and rethink their approach entirely.

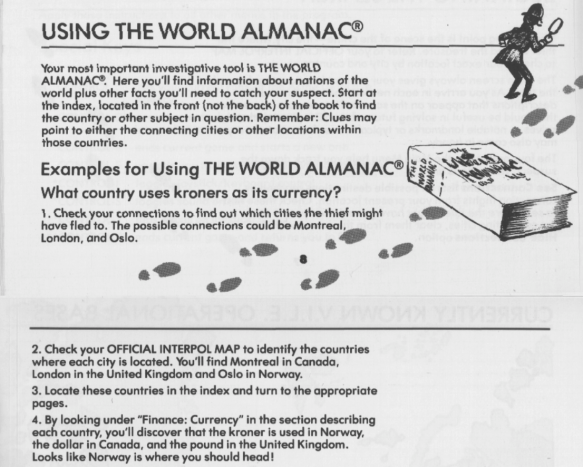

Unlike other kinds of educational games that often amount to rote drills to memorize facts and information, Carmen Sandiego encourages children to actively seek out information and learn for themselves, framing the discovery of knowledge itself as a kind of globetrotting adventure. Traveling to the wrong city is never penalized; the investigation can still continue if one simply jets to a new location. Players are not quizzed or made to memorize historical names and dates, but instead the game compels children to connect clues to destinations in service of a tangible, story-driven goal. The packaging of the hefty World Almanac and Book of Facts with the game further expands the parameters of gameplay beyond the computer screen, promoting interaction with outside educational texts. Even if the game is turned off, the almanac’s inclusion with the game embraces the act of browsing its pages as a form of relevant play, as though the young child were roleplaying as the curious ACME sleuth brushing up on intel for the next investigation to come. The World Almanac and Book of Facts thus functions like the Player’s Handbook of Dungeons & Dragons; the text is inseparable from the act of play. Indeed, Carmen Sandiego’s manual instructs players how to browse the physical almanac as though it were part of gameplay itself. The manual directs players to make sense of a clue that references kroner currency by referring to the almanac and examining the “Finance: Currency” section of any given country. Carmen Sandiego thus equates a successful ACME detective with one proficient in simply navigating the almanac.

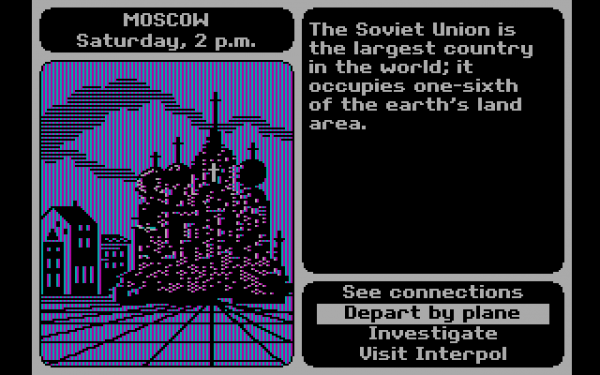

Much of the value of Carmen Sandiego stems from its willingness to introduce complex facts to young audiences, respecting the capabilities of children willing to learn. Geography and history are presented in ways that inspire curiosity. Countries are spoken about with enthusiasm, acknowledging and embracing rich cultural differences that one could potentially learn more about and encounter. The game doesn’t shy away from presenting topics atypical to standard elementary school education, making reference to the Kinyarwanda language of Rwanda and the Nepalese capital of Kathmandu (topics I don’t even know much about as an adult!). Players at a grade school reading level are even introduced to topics like colonialism, as one clue references a Southeast Asian country never governed by a European power (Thailand) and another clue acknowledges that the Mayans, Toltecs, and Aztecs maintained advanced civilizations prior to Spanish colonization. Such snippets of history serve as signposts for curious players to explore in greater detail with their almanac. When the game bluntly indicates, “Nepal was closed to the outside world for centuries,” players have the appropriate handbook to follow up on the reasons why this is so. Carmen Sandiego is even inscribed with the geopolitical concerns of the Cold War, making reference to countries now broken up such as the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia. Like any good educational game, Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? is simply the start of successful pedagogy, planting curiosity and questions in the minds of players that must be followed up by interacting with outside texts or engaging with a teacher who can address these broader themes in ways suitable for children.

Does Carmen Sandiego come with its own biases and exclusions? Absolutely. I don’t want to suggest that the intersecting lines between education and big corporate software companies is the answer to effective learning, as Silicon Valley is often more interested in developing players as a workforce and future customer base rather than knowledgeable, critical-thinking students. Still, there is value in Carmen Sandiego’s vision of globality, tantalizing players with alluring characters who are attractive because they are culturally sophisticated, cosmopolitan, and mobile. To be a global citizen is to understand cultures, peoples, and places beyond your own, the game seems to suggest, and these values are promoted as enjoyable and exciting. Even if young minds remain indifferent to the broader pedagogical value of the game, Carmen Sandiego remains more interesting than other educational games that simply task players with uninspired memorization. Instead, the game flies its sleuths to faraway destinations and casts worldly curiosity as a desirable attribute to cultivate and apply. Knowledge, like the elusive Carmen Sandiego herself, must be sought out.

Miguel Penabella is a PhD student investigating slow media and game spaces. He is an editor and columnist for Haywire Magazine. His writing has been featured in Kill Screen, Playboy, Waypoint, and Unwinnable, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.