Due Diligence: Wasting the Wasteland

Leigh Harrison’s analgesic of choice is Bethesda.

For some reason the games of Bethesda Studios act as milestones of my life. Each of its releases exist as very defined points in the sprawling mess of my personal growth, sitting as concrete waypoints I can look back on to embody a particular period of time. I’m wedded to them more than any other collection of videogames as a means of showing me I’m aging. They sit alongside deaths, births, tragedies, and delights in calcifying a certain moment. There are people who remember a time through its friends, or songs, or lovers—I remember the Bethesda game I was playing.

I was on holiday when I first came across Morrowind. My family used to go to the coast a hundred or so miles away from where we lived, which was lovely, except lots of my friends “went abroad” and so my youthful brain, as they often do, felt a bit shortchanged. There were beaches, a harbour, amusement arcades, cabaret acts, dinners out, beautiful walks, ice creams, donkey rides, and fancy wall-mounted TV sets. These all sat alongside healthy doses of those much rarer things, like youthful escape, loving warmth, and a blissful existence with parents who loved me dearly—but all I could think of as I grew older during high school was that we didn’t go to Spain or Portugal like all the other boring people. I appreciate that airports are horrible places now, but back then, especially as I approached the legal age to partake in most activities, I was a bit self-conscious of my staycations (I resent myself for using that word). I’ve been to loads of countries since, and to be honest I still yearn to revisit the places my parents took me to, but there’s no accounting for the pressures of youth when you’re beset by them.

During one of my later adolescent holidays I was an avid reader of PC Gamer magazine. In it there was an advert for their branded run of “gold edition” games: year or so old tiles that they sold via some cobranding publishing deal on the cheap. Morrowind’s ad boasted “200 hours of gameplay” and “a wholly player-driven experience” and had me sold at the unsettlingly strange price point of £14. I don’t remember much beyond its giant mushrooms and that all the subsequent Bethesda games are a lot like it—just much easier to get a handle on.

When Oblivion came out we all scrambled to it. It was, like, a massive big game with Patrick Stewart in it. I went round my friend Tom’s house to play a pirated copy on an old PC. We were greeted by a horrible mess. Screenshots always lie, but what we got out of his whirring box of about-to-explode plastic and metal was atrocious. There’s a point in all these Bethesda games where the player exits the underground tutorial area and first encounters the open world before them. This is supposed to be an exhilarating moment that heralds the giddy exploration of the rest of the game. We, however, were presented with a grey lake of choppy textures surrounded by utility pole trees and skittery, cube-shaped crabs. We abandoned it and went back to playing hidden object games before going out underage drinking.

I returned to Oblivion during my first year of university in London. You know what it’s like: you take a cripplingly huge loan from the government to go and study a subject you’re super-passionate about (film, in my case) so you can develop a better understanding of it, yourself, and the world. But somewhere along the way, thanks in part to all the financial and emotional mollycoddling you’re receiving, you end up feeling so entitled that you put in just the bare minimum to scrape through and spend the rest of your time partying in whatever capacity. My parties were actual parties—ones based in flats, houses, bars, clubs, and a variety of unspeakably grim outdoor locations—and solitary videogame ones. Because the smoke detectors in our dormitory rooms didn’t detect smoke at all, all you needed was a thick sock and you’d unlock the potential to never actually have to leave your squalid room. And so sometimes I didn’t.

Oblivion worked properly on the standardized hardware of my PS3, so the moment I first emerged from the darkness was genuinely as striking as intended the second time round. The screen goes almost white at first, blinding you as if the scene before you were on a par with meeting your deity of choice. FLASH. “This is amazing, just in case you aren’t sure how to react.” After that your vision begins to slowly clear as the brightness drops and the colors start to look like they should. It takes a good second or so for this to happen, which is about long enough for the game to convince you it’s amazing. That moment is honestly great. It conveys scale—your physical, if not actual, insignificance within the world—while also acting as a little visual metaphor signaling a shift. “Dude, forget about those other games, THIS right here is where things are going.” Morrowind was a game for people who sat in their bedrooms for too long; Oblivion was for the people who still did that, but they smoked and drank beer while they played and sometimes left to go and do other things. Oblivion, with its scale, relative simplicity, prettiness, and Patrick Stewart, is maybe the single coolest RPG ever made.

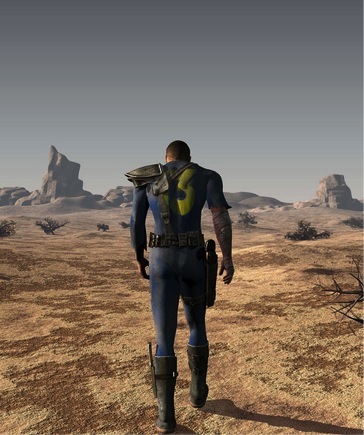

I was far too young to have played its predecessors by the time Fallout 3 was released at the beginning of my second year of university. But, like most people I knew, I just approached it as Oblivion with guns. Which it totally is. It has the same blinding emergence into the open world, a similar levelling system (in that it has one; they all perform the same function really), the same types of enemies, the same quest-driven structure, and the same massive, sprawling landmass. But this time everything is set in a messed up post-apocalypse and you can explode heads with guns. Impact-wise Fallout 3 didn’t come close to Oblivion’s level of cool—I’d already seen all its tricks before—but it was still super, super, well, cool, and appealed to every facet of my 19-year-old sensibilities.

“Cool.” I keep using the word to describe these games, not because I can’t think of a better one but because it’s true. They are painstakingly created to appeal to as wide an audience as possible, existing as massive mishmashes of all the things people like. Huge worlds, hundreds of hours, Hollywood actors, pretty visuals, orchestral soundtracks, stories for you to care about should you choose to—Bethesda games are emblems of contemporary blockbuster videogames. But, and I only partially recognized this back then, I don’t actually like contemporary blockbuster videogames a great deal—I simply consume them because they exist and are easy.

Once the initial “oh, this is cool” shock wore off of both Oblivion and Fallout 3 I just went through the motions as I whiled away my hours not really concentrating. Slouching goggle–eyed didn’t really bother me back then, because I almost always played games accompanied by a two liter bottle of cider and an overflowing ashtray. As soon as I began to get bored or encountered a bit of loading screen down time, I’d roll up a cigarette, pour myself yet another glass of mass produced alcoholic apple juice, and then more than likely have something mildly distracting to do once I’d readied myself. At the time it seemed like a fairly smart thing to be doing. I worked for a horrible Irishman named Shawn, selling TVs and cable subscriptions to East Londoners who couldn’t really afford them, and saw my few hours of drunken respite as a little treat for putting up with my fairly rubbish lot in life. I got by.

As my graduation drew near I continued down this road. I worked thankless retail jobs, did my university work, drank, and played videogames. I played a lot of videogames, though I don’t remember a great deal about them because I was drinking quite heavily, having got to the point of always playing when drunk. Fallout: New Vegas isn’t a Bethesda game really—it was made by Obsidian, the people who seem perpetually destined to make sequels to other people’s games—but it is so similar to Fallout 3 that a passerby wouldn’t notice the difference. After university I was all fresh faced and optimistic about my career prospects and so ended up interning whilst also working full time in yet more shops and a bar. My 70 hour weeks were comprised almost entirely of work and heavy drinking by this point, and I’d comfortably put away four or so liters of lovely Polish beer and a bottle of some kind of wine a night (normally white, but I did like port a lot). On my few days off it would be significantly more. I was super excited about New Vegas because I’d loved Fallout 3. Looking back now it’s clear that this was a twin nostalgia, as I sought to recapture not only the joy of the game itself but also the time in which I played it. My film degree had been great, and I’d made some little shorts that I’m still quite proud of to this day, and I’d done so with people I still occasionally see from time to time. They were good days.

But my life was not like that by the time I was playing New Vegas. Working a lot in service sector jobs breeds a very strange type of isolation. You find yourself in a place where most of your social interactions are with people you know almost nothing about and who don’t want to or aren’t able to share more of themselves. Working in shops and bars is exhausting, and you’ll often find yourself under a team of bosses who are more than happy to bleed you dry of your every ounce of strength, both the physical and emotional kinds. Because of this, and the general lack of regard we in the western world have for service sector workers, there is a lot of employee transience. Nobody wants to work behind a bar, at least where I live, because it’s horrible and people treat you like trash. So you just keep your head down. You work your 12 hour shift for minimum wage and then go home—in my case to drink a whole load of booze, smoke a lot of cigarettes, and fall asleep in my clothes.

Unsurprisingly, I don’t remember much about New Vegas. Or Skyrim for that matter, which I’ll lump into this discussion because I feel exactly the same way about them both. I was at my lowest point when interacting with them and only really did so because they kept me awake while I drank into the morning. Lots of booze makes you really sleepy, and I dearly didn’t want to set myself on fire after passing out at my desk with a cigarette in my hand. Beyond this matter of depressing practicality, I found them both to be real drags. They are almost exactly the same as the games that came before them. They have the same shortcomings as well: the mannequin people, the copy-pasted quests, the levelling systems designed to keep you playing by dragging progression out to a snail’s pace, and the thousands of loading screen cigarette breaks that may well lead to my untimely death. Neither of them is a bad game, they are just no different to ones I’ve already played.

It’s becoming increasingly common for us to discuss the glitchy nature of these very big videogames, but I wouldn’t say this is because they are any less polished upon release than they were 5 or 10 years ago. I think we’re more prone to being critical of them because we’re not playing Morrowind or Oblivion or Fallout 3 anymore—we’re playing New Vegas or Skyrim or Fallout 4. We talk about the mangled faces of Assassin’s Creed Unity because that’s all there is to talk about: the rest of the game is almost exactly the same as the one we played the year before, and the year before that, and the year… etc. etc. I’m not going to play Fallout 4 at all for this very reason. I don’t need to put myself through it all over again.

I stopped drinking to excess some years ago, but only after a lot of embarrassment and pain, and the help of an unwaveringly strong woman. Over the years many people shared their concerns about my behaviour. Friends, family, and colleagues all told me to stop, but it was never going to be that simple. Nothing ever is. The funny thing is they only ever saw me at my “best”—when I was just too drunk for my own good—and not all the other times I deliberately hid from them out of shame. They never saw me drinking at ten in the morning, or on the train to work, or as soon as I left work, or at work. They never saw me throwing up in my mouth as I rode the bus, or dry retching every morning as my body shouted at my stupidity. They, luckily for them, never saw me shit myself—which I did more times than an adult should ever do. They also didn’t see me pour hundreds upon hundreds of hours into videogames I had absolutely no interest in playing beyond using them to try to recreate a time before I spent most of my life intoxicated.

I find it really hard these days to play long games. They are too indulgent for my spoiled palate. Back when I did nothing with my life they were the perfect enabler, allowing me to justify my gluttony and poor choices. Without the videogames I’d have simply been a pathetic young man who sat around all night drinking by himself. With them I was a drunk king, sitting in one cold, dirty room after another constantly striving for greatness. Like every career drinker I imagined myself as a heroic Bukowski figure—I was enjoying my life to its fullest, making my own rules and breaking everyone else’s. The games, in providing me with cheap, hollow rewards, covered up the sad reality of my existence. Now that I don’t need their distractions, I cannot play them anymore. Their futility is blinding. I can’t escape it. They are massive, empty expanses filled with things I have no interest in—maybe never did. Now whenever I emerge from a cave or underground vault I’m not met with wonder and intrigue. I just see another hundred hours I’ll never get back, and I’ve already wasted enough for one lifetime.

Leigh Harrison lives in London, makes DVDs for a living and owns a hamster. He likes canals and rivers a great deal, and spends a lot of his time walking. He occasionally says things about videogames on the Internet, and other things on The Twitter.