Due Diligence: The End is NieR

Yoko Taro’s masterpiece is a miserable pile, like all true art.

Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music is an album of nothing but swirling, modulated guitar distortion. Originally released over four agonizing sides of pitch black vinyl, it is practically unlistenable, though also strangely alluring in its earnestly bizarre way. It is simultaneously held up as some of the worst music ever released, a bold artistic statement, and a major progenitor of the Industrial genre. Similarly, Lars von Trier’s Nymphomaniac is five and a half hours of rubber cocks, ultraviolence, and a DIY abortion. More than the sum of its parts, the film’s explicit imagery and themes eventually coalesce into an excruciating, deeply affecting exploration of a self-abuse borne of unfulfilled desires and everyday loneliness. The landscapes of Lowry, so celebrated where I’m from they’ve become almost kitsch, nonetheless lay bare the regimented bleakness of life in the industrial north of England.

The pointless and vapid question of “are videogames art?” wouldn’t leave me throughout my time with NieR: Automata. I’m not saying that texts have to be uncomfortable or abrasive to be considered art—Dan Brown’s oeuvre and the High School Musical trilogy put pain to that theory. But I do get the impression that the game’s director, Yoko Taro, subscribes more to the “misery loves company” school of art than the “expertly staged basketball number” one.

Viewed in this light, he’s led development on a game that is a staunch success. Automata is complex and often impenetrable, pointing to a higher purpose the wider medium might achieve, should it choose to strive. It is also, as if to offer a confident counterpoint to those still fixated with discussing ludonarrative dissonance on a weekly basis, a rare example of a game that is both a tale of misery and miserable to play. Automata is largely devoid of entertainment or fun, and like everything simultaneously well respected and lacking levity, I’d say that probably makes it art.

You play as 2B, a combat android running missions against the hordes of robots that now inhabit Earth. Centuries hence, aliens invaded and all but wiped out humanity, the remnants of which now hide in exile on the Moon. 2B is part of the YoRHa elite android force, tasked with carving the not-so living stuffing out of any and all robots she comes across. You’ll quickly team up with another android, named 9S, and together fight for mankind’s survival and rightful home.

Along the way, the dynamic duo do battle with robots the size of oil rigs, a pair of verbose anime-ass bad guy androids, zombie robots, dog robots, Catholic robots, and Metal Gear Ray. 2B is equipped with the standard melee attacks, dodges, and counters that make up the action/adventure genre, and makes light work of most enemies in regular combat . Automata frequently switches things up, putting 2B in a flying combat suit and turning the game into a bullet hell shooter. These are welcome distractions from the often button mashy melee combat, which doesn’t require a huge amount of thought on the standard difficulty.

That’s it, really. You explode a lot of robots, find out the aliens were dead the whole time, slash and shoot your way into and out of trouble, and eventually defeat the proselytizing Big Bads. There are a couple of more memorable sections, like a joyously weird trip to a theme park staffed by friendly robots dressed as jesters and clowns, and a side scrolling jaunt to find a baby king that takes on the aesthetics of a Castlevania, if not the labyrinthine architectural sensibilities. But by and large, Automata falls a bit flat in the grandiosity stakes, ending up a patchwork of funny/touching/cool-as-shit set pieces stitched together with reams of packing twine.

That’s because the ending of Automata isn’t really the ending, and more just a means to get to another beginning. The second time you start you play the whole game again as 9S, a reconnaissance android running missions against the hordes of robots that now inhabit Earth. Centuries hence, aliens invaded and all but wiped out humanity, the remnants of which now hide in exile on the Moon. 9S is part of the YoRHa elite android force, tasked with carving the not-so living stuffing out of any and all robots he comes across. You’ll quickly team up with another android, named 2B, and together fight for mankind’s survival and rightful home.

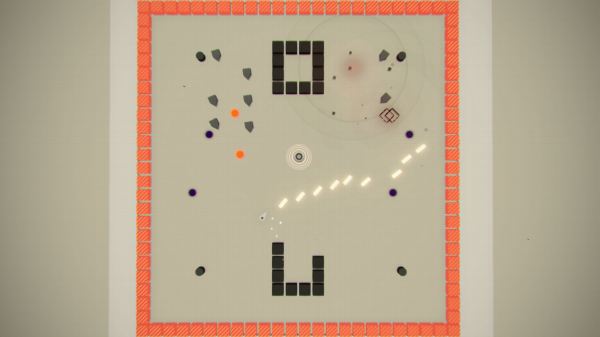

Along the way, the dynamic duo do battle with robots the size of oil rigs, a pair of verbose anime-ass bad guy androids, zombie robots, dog robots, Catholic robots, and Metal Gear Ray. 9S is equipped with the standard melee attacks, dodges, and counters that make up the action/adventure genre, but also has the ability to hack into enemies. Infiltrating a robot brain triggers a hacking minigame, which takes on the form of a bullet hell shooter. You must navigate a little ship around obstacles while shooting enemies which, once vanquished, allow you access to the machine’s core. Destroying this will usually one-shot regular enemies, though larger ones must be hacked multiple times before they go down. Automata frequently switches things up, putting 9S in a flying combat suit and turning even more of the game into a bullet hell shooter.

That’s it, really. You explode a lot of robots, find out the aliens were dead the whole time, slash and shoot your way into and out of trouble, and eventually defeat the proselytizing Big Bads. Again. There’s a point to all the repetition, of course: it’s there to make you think. Like, really think.

During the first run of the game, you meet a village full of friendly robots. They’re not like the theme park ones, all mechanical proxy and harmless learned routines; they’re more human than that. They huddle around in family units, revel in social niceties, and discuss the finer points (or lack thereof) of 19th century philosophy. Later, when playing events again from 9S’s perspective, you’re given deeper insight into the backstory of a number of enemies. The baby king in the castle, for instance, is really a great and gentle leader whose mechanical body has failed him. His consciousness has been placed into a tiny, child-like body that his followers mistakenly assume will grow into a great and gentle heir. Except he won’t, of course, because robots don’t grow up. It’s a lot more poignant seeing him get sliced in half knowing this.

While your enemies are humanized plenty during the first playthrough, it is the second run that adds more nuance to the “we’re not so different you and I” platitudes Automata constantly peddles. But perhaps more successful than any of the admittedly touching backstory reveals, is that in making you play through everything a second time, the sheer boredom of the experience breeds pacifism into the player.

9S is significantly weaker in melee combat than 2B, so direct aggression is nowhere near as viable in the second playthrough as it is the first. This means that should you choose to fight, hacking is the only surefire way of engaging enemies, resulting in you dipping in and out (and in and out) of the bullet hell minigame for hours upon hours. With its small playfields and limited variations—there are perhaps a little over a dozen minigames for regular enemies—I read hacking as the game willing players to tire of combat. It is more abstract and less visceral than melee engagements, and feels as much a repetitive chore as a means of progression. Hacking is easier than swordplay, but nowhere near as enjoyable.

As a result, I quickly began skipping over non-mandatory combat altogether. There were still plenty of boss robot heads exploding, but where I’d previously fought my way through levels and defeated every last enemy, the second go around, I was happy to take the path of least resistance and leave as many robots to their own devices. They all die at the end anyway, so I thought it best to let them have their fun while they still could.

Oh, but they don’t all die at the end. Because the second ending is really just the third beginning!

The third run of Automata feels like a mod or cool bit of DLC. It picks up shortly after the ending of the first two playthroughs, and continues the story by introducing a MacGuffin and having you collect X number of things to open it. 2B dies, 9S develops the capacity to feel grief and unbridled rage, and you get to play as A2, a bad guy who’s only a bad guy because you were probably working for the bad guys all along.

Everything runs at quite a clip, with events chopping between the two protagonists every 40 minutes or so. 9S is trying to open up a mysterious tower that emerges from the ground, and has to trawl through copy/pasted dungeons killing things while growing ever more unhinged. A2 just plain hates robots, so all she does is find them and kill them. Both plots see you visit locations you’ve previously visited many times before, to fight (and hack) enemies you’ve murdered many times before.

Throughout what proves to be its final act, Automata finally gives up its secrets. Like the aliens, the humans have been long dead, and only their genetic data lies partying on the Moon. YoRHa androids are actually part of a grand training operation; sent out to gather enough combat data for use in a new, more advanced line of soldiers, and intended to be fully expendable once enough operational information has been harvested. Androids are built around deconstructed robot tech and are, in fact, not so different after all. 2B is really 2E (or Execution), and has killed and reset 9S, who regularly discovers the above truths, hundreds of times in previous missions.

In what I consider the best ending, 9S goes insane with rage at learning that, like humans, there is no true purpose to his existence, kills A2, and then travels to the Moon in spirit form to wipe out the remnants of humanity. Like the rest of the game, you can play it a few different ways, but this one seemed the most fitting.

Fucking NieR: Automata. I’m drawn to it and repulsed by it in equal measure. While nothing mindblowing, its exploration of what it means to be alive is largely unparalleled within the medium. Is free will important if our individual lives are inherently meaningless? Can a cause ever be considered just when the elite will inevitably exploit age-old power structures for their own ends? Why do we insist on focusing on minute differences and not the near infinite things uniting us? In exploring humanity through the lens of robots and androids trying to replicate the human experience, Automata points to how truly lost we are as a species.

One in-game document details how, for tens of thousands of years, the robots attempted to reproduce human behavior. If one government fell, it tells us, they would not alter their approach but simply try again, unmoved and unchanged. It’s a heavy-handed sentiment, but it points to the robots following our example more closely than any character in Automata could possibly appreciate. For what is more human than insisting on repeating one’s mistakes in perpetuity?

While a lesser game would simply tell players all this, Automata insists we live it. The wholesale retread of 2B and 9S’s story is a blunt instrument with which the game beats its ideas into us. It doesn’t just want us to appreciate how pointless the robot/android war is, it wants us to feel it through unforgiving repetition. We might play the game differently thanks to the new hacking mechanics, but the result is always the same. Nobody comes out of it better off. Similarly, the reconfiguration and repackaging of the third playthrough—telling a new story with the same constituent parts—works as a metaphor for the countless versions of 2B and 9S’s previous encounters, and thus the countless times humanity has fucked it up for ourselves.

Automata isn’t fun to play, and beyond its large-scale existential musings, is impossible not to read as a scathing critique of videogames themselves. It tells a story of meaningless death and destruction, but has the confidence to make partaking in that senseless violence utterly unenjoyable. Killing things is a chore, and the game uses narrative and mechanical repetition to highlight how violence-centric videogames are so hollow and joyless. By the time I reached what would traditionally be the triumphant third act, fighting my way through a second almost identical to the first had utterly broken me. I was 9S: struggling towards a sense of finality I simply needed to reach. But not because I believed I was striving to improve things or even for my own personal validation, just simply because I wanted the experience—the cycle—to end.

Leigh Harrison lives in London, and works in communications for a medical charity. He likes canals and rivers a great deal, and spends a lot of his time walking. He occasionally says things about videogames on the Internet, and other things on The Twitter.