Due Diligence: Stick with the Prod

Leigh Harrison knows how to make a silent takedown.

As the old philosophical quandary goes, “how do you kill that which has no life?” Yeah, on the one hand it’s a fun little dig against stereotypical players of videogames, the basement dwelling sort who’ve been all but replaced by evil teenagers who take great pleasure in digging up your personal information and threatening to murder you. But beyond that, it actually raises a heady question. What is it to kill?

Back in 2013 I drunkenly cobbled together a treatise of sorts on “real violence” in games. In essence, I reckoned that death is overused, and that this can be rectified not by simply removing violence all together, but by making it genuinely upsetting. You know, don’t wimp out and insta-kill snap a neck, instead be forced to repeatedly smash someone in the back of the head until, after a half-dozen blows, they finally collapse and take another minute to die in front of you, blood and life pouring out in all directions.

Despite my profound insights, games haven’t altered much since then. While nowadays we can all discuss the implications of digital homicide to a certain extent, in many cases killing is still the only thing we can do to most characters in games. As I said back when I still had the hopeless notion of becoming genuinely thought-provoking one day, enemy alive = bad, enemy dead = good. Beyond crushing personal realizations, nothing much has changed.

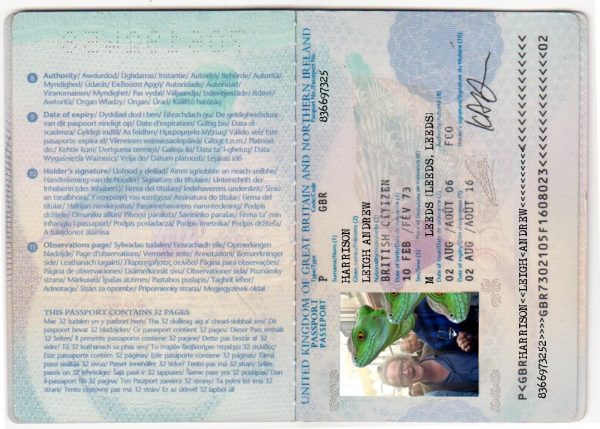

But what happens when a game does give us the option of not killing? Well, as it happens, serendipity has smiled upon us all and I’ve recently been enthralled by Deus Ex: Mankind Divided. Not only does it feature the sort of non-lethal combat you don’t find all that often, but in making its dystopian crumbling society hit home by mirroring our own, it’s also got a shadowy cabal of tech-savvy, though not necessarily pre-pubescent, evildoers who’ll destroy all in their path. Now, I know the mere mention of the Internet Illuminati’s existence can anger them, so I attach the below copy of my passport to save them the time having to look me up. I expect to hear the sirens any minute.

For some self-flagellating reason I decided to play Mankind Divided non-lethally, perhaps as a petty means of asserting moral superiority over others. As we’ve discussed, videogames are often about little more than men with guns shooting other men with guns until they fall over, either because they are dead or because I have made one deftly remove the other’s legs. Indeed, Mankind Divided offers me this very scenario right at its beginning, when it asks if I prefer to see my exploding heads up close and personal or from the comfort of a 4x magnification scope. But it also gives me the option of preserving the sanctity of life (yes, even the ones of brown people on the Arabian Peninsula for once), by offering ways of putting people to sleep in a literal sense, rather than a romanticized version of boring a hole through someone’s brain at 3200 feet a second.

Non-lethal violence actually makes a lot of sense within the context of the game, given I play a gruff male model INTERPOL policeman, Adam Jensen. In fact, that I’m even given lethal alternatives at all speaks a lot more of videogame conventions, not to mention the increasingly trigger-happy nature of contemporary policing, than it does any internal narrative logic. Regardless, I took the high ground and the high road, and grabbed my tranquilizer rifle and stun gun as I set off to right some wrongs.

In Mankind Divided, every single armed foe, including all the robots, carry guns. Pistols, shotguns, assault rifles, sub machine guns, revolvers, sniper rifles. Guns. If they shoot at me, I die. Guns. From the game’s first mission they’re everywhere, and they only get bigger and more lethal the further in I go. Very much like the argument against nuclear disarmament, Mankind Divided shows me a man with a gun and tells me that the only way to compete with him is to be a man and get a gun. Preferably a bigger one, like all those it hides in car trunks and other people’s houses.

It wants me to want its pretty guns. There are loads of them, for a start, all different shapes and sizes, all with fancy alternate ammunition types and upgradable parts. My tranq and stun weapons, on the other hand, are super boring. They shoot “darts” and “shock things” really slowly, and can’t be improved with cool distractions like red dot sights and damage enhancements. They suck, really, especially when compared to the proper guns.

And because my enemies all carry these more exciting death-dealers, they’re everywhere. Accidentally knock a guy out with the refrigerator I threw from a window and he’ll drop a beautiful pump-action shotgun for me, as if he’s thankful to be concussed and in the rain. There are more guns in a square block of Mankind Divided’s Prague than all the streetlights, benches, and discarded inhalers of future-drug Neon. The non-lethal ones, in comparison, are rarer than hen’s teeth. I think I found about five of each of them in all the hours I played. I regularly stumbled into individual rooms filled with more pistols and grenades than that. Mankind Divided, it would seem, wants to make a point: pick up a gun and shoot some dudes, this is a videogame after all.

You’d think that any non-lethal option should be harder, then, given the game sets it up as being such a pronounced deviation from what’s expected? You would, wouldn’t you? Totally isn’t. Guys go down with a single shot, bro, no joke. The stun gun, especially, has ridiculous stopping power. Regular enemies collapse with one shot, wherever I hit them. Stronger ones, wearing power armor or the body of the game’s one and only boss, need to be darted and then punched in the face. Literally all there is to it. And it’s not like the game shoehorns in some exposition to justify this power, it’s just the way it is. From what I can tell, if stun gun rounds hit flesh they taze, if they hit armor they function in an EMP capacity; rendering any electronic device, like a power suit or giant killer robot, entirely impotent. They are, effectively, a one-size-fits-all solution to every problem.

Shooting dudes in the head, however, is a lot harder. All those flashy ammo types, all those bigger bullets, actually mean something beyond phallic iconography. A taze and a slap does indeed take down a heavily armored foe, but to do the same with real guns involves unloading a half magazine of armor-piercing rounds, more if you’re going in all silenced. Likewise, that pushover final boss might take a grenade launcher, EMP assault rifle, and 10 minutes, but with my patented “three-shot stun and right hook combo” it took circa 45 seconds, including all the flapping about getting my bearings.

I can only imagine that Mankind Divided’s stance on non-lethal violence is more a grand polemic than anything to do with unbalanced play mechanics. That in creating an environment where guns and killing are implicitly encourage, yet less effective than non-lethal means, it is making a concerted attack on the current state of videogame violence-for-its-own-sake. This is, after all, the same game that allows you to bypass large swathes of itself via endless tracts of ventilation ducts. Could it be that, like Far Cry 2 before it, Mankind Divided seeks to hold a mirror up to its players and have them ask difficult questions of themselves? What is is to kill? Why do we do it when the alternative is so much simpler?

Because killing is still everywhere in games, and when it’s so prolific it loses all meaning. Like The Chessboard Killer Alexander Pichushkin — or any serial killer for that matter, but he works especially well here because he symbolically/arbitrarily wanted to kill exactly 64 people and fill a chessboard — once killing becomes part of a recognizable and repeatable pattern we lose all attachment to it. We instead chase a high, whether it be score, flow, or endorphins, and focus on the result rather than the act itself. Maybe this is what Mankind Divided wants us to reconnect with. Maybe, in making it easier to spare a life than to take one, it wants us to question why a non-lethal approach should ever be seen as the alternative in the first place.

Having said that, it’s difficult to know where Mankind Divided’s intentions truly lie. Just like its awkward marketing throwing about insensitive and shortsighted phrases like “mechanical apartheid” and “Augs Lives Matter”, and it allowing me to circumvent its entire character leveling mechanic with microtransactions, its non-lethal combat doesn’t stand up to thematic scrutiny. After that opening mission where I first chose not to kill, my handler congratulated me for my restraint and leaving a bunch of people we’d be able to “interrogate” — let’s not get started on unpacking this one. After that, however, there was no further mention of my pacifism until the very end, when Adam tossed off a line about the final boss not “deserving to die simply because he’s on the other side”. It’s acknowledgement, yes, but only in the most superficial of ways.

Likewise, there are instances where combat of any kind can be avoided through smart conversation. In these situations, I was presented with three dialogue options to choose from, one of which continued the negotiation, while the other two led to guns being drawn. After successfully navigating four or five of these choices, my opponent would concede and come in peacefully. It’s another nod to there being more than one way to skin a cat, but these opportunities were prescribed by the game; I couldn’t use my silver tongue to bypass every enemy, just the ones certain missions allowed me to.

All of Mankind Divided’s many choice-centric mechanics feel similarly non-committal. I can crawl through a vent, punch a hole in wall, hack a door, smash a window, or move a metal crate to get into a room — but all roads eventually lead to Rome. This is faintly humorous when environments have a half-dozen entry points just so I can pick my favorite, but having a similarly pragmatic stance on whether I kill or not — when the game is actively giving me the choice — seems somehow perverse. Mankind Divided’s narrative explicitly points to issues of racial prejudice and heavy-handed policing of minorities — subjects ripe for exploration via player choice — yet it’s happy to leave them as framing devices for its story of hackers, secret world governments, and “who can you trust” intrigue.

Adam Jensen, as a cyborg (and thus othered) protagonist, forced to fight his own people on behalf of a society that despises him, is about the closest a typical caucasian male videogame character will ever get to viably tackling issues of racism. But he never does. He might sigh every time he’s asked for his papers on the subway, he might tacitly disapprove of the jingoistic rhetoric of his colleagues, he might even say out loud that “y’know, augmented people are human, too”, but his narrative actions are entirely separate from my player ones. Whether I slit a thousand throats of my cyborg brothers or lay them down to sleep with the compassion of kinship, the game and everyone in it could care less. Nothing that happens outside of its “racism is bad, bro” cutscenes matters.

Like most of Mankind Divided, and Human Revolution before it, the options I’m given seem to exist only because the original Deus Ex offered them. On a purely mechanical level this is fine, but had the game chosen to discuss the meaning held within its myriad approaches, to explore why we might choose one path over another and the ensuing implications, I might have come away from my non-lethal run with something more valuable than a trophy glibly informing me that “bosses are people, too.”

Leigh Harrison lives in London, works in communications for a medical charity, and owns a hamster. He likes canals and rivers a great deal, and spends a lot of his time walking. He occasionally says things about videogames on the Internet, and other things on The Twitter.