Due Diligence: Pictures of Matchstick Men

Leigh Harrison thinks broad strokes make bigger characters.

When I was 11 I graduated from lower school. On our final day a big party was thrown in celebration. At the end of it I bawled my eyes out, scared of how difficult it was going to be surviving without my classmates. I was moving to a different school from most of them, so maintaining our friendships, I’d clearly already decided, was going to be impossible. Despite being prepared to jettison the previous seven years of camaraderie almost immediately, I was still very upset about what was happening. Quite why I’m now not sure, because 11-year-olds, by virtue of having existed for little over a decade, don’t really have that much to offer one another. They are essentially sketches, containing only the most basic elements of a person. Don’t get me wrong, 11 is one of the best ages we’ll all ever be, full as it is of exciting developments, existential awakenings, and tentative romances. The beauty of being 11 is not solely about experiencing things for the first time—it is more important that we’re able to mess everything up and start over, having none of it really count for much. These precious pre-teenage years are so important because they are meant to be entirely overshadowed by what comes after.

I recently left the place I’ve worked at for four years, and as I wrote my resignation letter I again bawled my eyes out. I want to move on, but I dearly love the people I’ve worked most closely with, and the thought of not seeing them every day still makes me sad. But when you think about it, these people you spend half your life with are rarely much more fleshed out than your average 11-year-old. Not in intellectual terms, but in the depth of our understanding of them and the relationships we share. We know little bits of their lives, broad strokes: wives, husbands, children, weekend activities, living arrangements, taste in red wine. We hardly ever get right into their being and see just what makes them go. We don’t really know the people we’re surrounded by very well, so we find connection and meaning in the small things.

There are a couple of lines from the Evening Standard’s review of the disaster film San Andreas that I can’t seem to get out of my mind, and I think they illustrate this point quite well. “He goes home and opens a letter containing divorce papers, but instead of even crunching them up he lays them down gently and quietly.” At first I read this to be sarcastic, a dismissal of the film’s attempts to be more than a crash bang wallop video about buildings falling down and Dwayne Johnson doing the business. But it isn’t; instead, it’s a genuine compliment about an important bit of nuance. We don’t know very much about Johnson’s character, Ray, but this moment gives us enough of him for us to understand so much of what we’re not privy to. In seeing how he navigates anguish and frustration we’re shown a great deal of his personality in a single, silent moment, which gives the film more time to concentrate on throwing skyscrapers into one another. It’s a piece of very economic filmmaking, and displays that very truest of almost-truisms: “less is more.”

There are a couple of lines from the Evening Standard’s review of the disaster film San Andreas that I can’t seem to get out of my mind, and I think they illustrate this point quite well. “He goes home and opens a letter containing divorce papers, but instead of even crunching them up he lays them down gently and quietly.” At first I read this to be sarcastic, a dismissal of the film’s attempts to be more than a crash bang wallop video about buildings falling down and Dwayne Johnson doing the business. But it isn’t; instead, it’s a genuine compliment about an important bit of nuance. We don’t know very much about Johnson’s character, Ray, but this moment gives us enough of him for us to understand so much of what we’re not privy to. In seeing how he navigates anguish and frustration we’re shown a great deal of his personality in a single, silent moment, which gives the film more time to concentrate on throwing skyscrapers into one another. It’s a piece of very economic filmmaking, and displays that very truest of almost-truisms: “less is more.”

The Unfinished Swan agrees wholeheartedly with this stance, opening with literally nothing, just a blank white screen. Fiddle with the controller for long enough and you’ll throw a glob of ink into the void, which flies a short distance before splatting across a white wall. Repeat this a satisfyingly large number of times and you’ll paint your way into spatial awareness, coloring everything in as you learn the difference between empty white spaces and the previously hidden objects, also white. The further into the game you go the more visual niceties you’re treated to, with color even making an appearance towards the end. Regardless of color though, there’s a unifying chunky simplicity running through the game’s architecture, as if the whole world were made up of a child’s box of wooden bricks. Indeed, everything takes place within a strange and magical land that our protagonist, Monroe, has found his way into, which itself lives within the game’s storybook framing device. The game’s visual treatment wonderfully reinforces its themes, with its simple architecture perfectly channelling the intricate but unfussy aesthetics of a Dr. Seuss or Quentin Blake illustration. Bold blocks of grey and white sit alongside one another, seemingly waiting for someone to come along and do something with them. Walls of stone, wood, and iron look to and interact with the player almost identically, as if the game itself were largely unfinished. As it happens, we’re actually stuck in the realm of a creative-yet-slovenly king, who, through the power of a superb brush, is able to paint anything he wants into existence. The only problem is he never truly finishes what he starts, just like Monroe’s recently deceased mother, also a painter. The evidence of this inconsistency is littered around the game’s visually stunning and intentionally sparse locations.

As you splosh your way around the king’s many creations you’ll encounter big, floating yellow letters. Hitting one with ink will reveal a page of the storybook you’re smack in the middle of and tells you a little more about the eccentric who built it all. The game’s narrative being modeled after a children’s book, each excerpt is very short, comprised of only a sentence or two. Their necessary brevity is actually a blessing, as they enhance and embellish upon the many environmental aspects of the game’s storytelling rather than attempting to carry the entire narrative. Each of the game’s four chapters offers up a new visual style and core mechanic, though they are all concerned with throwing ink at objects in some capacity. Every change brings with it a different era of the king’s life, letting us see what interested him at the time and the nature of his emotional state. The first chapter, for example, is orderly to a fault, featuring sharp right angles and Escher-style geometry. As we progress things become more slapdash and chaotic, signalling the changes occurring within their creator. By the end of chapter three we’re bathed in darkness, scrambling through a rickety wooden house that’s a far cry from the bleached splendor of his earlier creations. There’s only a handful of the storybook pages in total, but each sheds light on the questions posed by the game’s architectural storytelling. By their end we’ve been given enough little tidbits, both explicit and implicit, to more deeply understand the king’s motivations and character.

Again though, everything is very broad. The king is a man with a kingdom. He has ideals for that kingdom, but his people do not like them. He compromises, but the people are still not happy, so they leave. He creates a wife, but she too leaves, taking his unborn child with her. He retires and builds a giant monument to himself as a legacy, despite there being nobody left to see it. There is deliberately very little specificity to his story. Just like with Ray in San Andreas, we don’t need to know everything about his character to formulate a basic understanding of him, just a couple of exemplary instances. We can see from the pages and his creations that all the king really wants is to be surrounded by adoring people and remembered once he’s gone, but his inability to stick to a project, itself a symptom of always trying to please and strive for nothing but excellence, has left him alone and his kingdom empty.

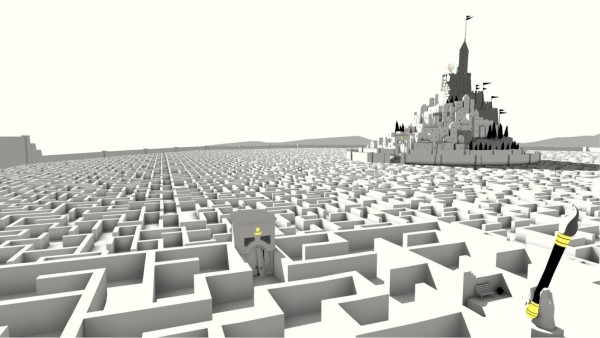

Image from Eric Guadara’s A Narrative Dream…

These narrative snippets all lay the groundwork for the game’s ending, where we take on the role of the king himself for a triumphant-cum-didactic finale that also acts as an interactive credits sequence (there’s a lot going on). As we step into his shoes we’re transported to a dream of his past in which a smiling young king looks back at us through a mirror. Even though the preceding narrative has been fairly insubstantial, it has been targeted and robust enough to make this moment a meaningful one. Knowing what we do of the king’s eventual trajectory, seeing the beaming, 2D cardboard cutout of his younger face is a wonderfully emotional sight. The king too seems self-aware, able to to finally understand where his life took irreconcilable swerves into madness, with even the hint that if he were to do it all again he’d change his ways. We’re transported back to a place where his good intentions could theoretically be borne out, where he could create and actually finish his masterpieces—where he could be happy. We don’t know much about him, but we know enough to be able to care and for this to be an extremely affecting moment.

As we continue it becomes clear that this is not a journey of self-actualization, but a good old fashioned cautionary tale. As our control reverts back to Monroe, we look down over the king lying in a coffin in a deserted hall, and we become the only one to witness the passing of a man who wished to be master of everything he touched. The Unfinished Swan, like the best children’s fiction, is a work of misleading simplicity, one that hides a rewarding and rich narrative behind its bold visuals and broad strokes. It speaks to the power of harnessing the little details, those almost insignificant pieces of information we learn about people every day, that something as simple as looking in the mirror and seeing the youthful face of an admonished character can be so striking. The action of being the one to walk up to that mirror is where the power of the moment truly lies: in the heartbreaking illusion of possibly having some agency over the affair. You can’t change anything, and you know so deep down, but for a couple of minutes and because of what you’ve pieced together over the preceding couple of hours, you really want to alter the king’s trajectory and save him from his fate. Meting out small amounts of information suits the nature of videogames because it means narrative can be communicated unobtrusively around the act of play. But here, where one such snippet—in the form of the ending—is in itself an exercise in very direct interactive storytelling, it can also be used to exploit and invert the participatory nature of the medium entirely, by suddenly wrestling that control back from the player, to heartbreaking effect.

The king and his lust to create perfection. Ray and his gentle resignation. Harriette Chidsey singing about Chupa Chup lollies at the year six leaving party. All the people I’ve ever worked with and the few pieces of themselves they’ve each deigned to share with me. None of it amounts to much really. But in their scarcity these little insights are all the more precious. Almost everyone we know is a stranger to us to a large degree, and we use these stories to feel connected to people we know almost nothing else about. When implementing them as a core storytelling conceit, we are able to very economically acquaint audiences with characters through exploiting our need to latch onto almost anything in an effort to bring emotional stability to our lives. Beyond simple self-preservation, I think it might actually be the most effective form of storytelling for a medium such as games. It fits neatly around the interactive mechanical elements—which one would assume should take up a lot of players’ attentions—while also delivering jolts of invaluable emotional sustenance. It would appear that we’re more than happy to fill in narrative blanks for ourselves anyway, so protracted expository bouts mightn’t always be necessary or even desireable. Regardless, much like Flower, Ico, Baywatch, and being an 11-year-old ourself showed us years ago, The Unfinished Swan perfectly communicates that we don’t need a huge amount of depth in our characters for us to still care strongly about them.

Leigh Harrison lives in London, makes DVDs for a living and owns a hamster. He likes canals and rivers a great deal, and spends a lot of his time walking. He occasionally says things about videogames on the Internet, and other things on The Twitter.