Due Diligence: Never bet your head (A tale with a moral)

Leigh Harrison howls at the moon.

Emerging from the darkness of the stairwell, Barristan Selby found himself in the belly of a decaying chapel. The place was in a right state. Broken pews littered the nave and gaunt, dusty shrubs grew at jagged angles from the walls. They looked dead to him, but maybe that was just the way they grew in Old Yharnam. He didn’t know, he wasn’t from around here. Or a botanist, to be fair. He had been an architecture undergrad for two years, though, before he switched to beast hunting. His experience told him that with so few columns left intact to support it, the roof could well collapse at any minute. Taking no chances, he made for the door.

“Hear ye, oh hunters,” read the erudite note nailed across both leaves. “There be monsters here, granted, but I have it all under control. I appreciate you hunters are a unionized workforce, and thus this request is impinging on your right to gainful employment, but I implore you to stay away. Yours, Gentleman With a Massive Chain Gun.”

Tearing down the note with maximum incredulity, Barristan flung the great wooden doors asunder. He’d been told his whole life he’d never be good enough to join the hunt. Not strong, or quick, or skilled enough to chase down the beasts of the neverending night. But he’d made a promise to his parents, as they lay disfigured and dying in the road, that he would avenge them. That he would bring swift death upon the monsters, just as they had brought it unto his family. “This is for you, mom and pop,” he thought, as he crossed the threshold and entered the ochre-tinged stillness of the night air.

I’m not Filip Miucin, the disgraced IGN editor and plagiarist extraordinaire—which is a great shame because I spent my two month sabbatical trying to shapeshift into him to make this triumphant return a valid, fact-based affair. Instead, I’m just going to have to speculate and make huge leaps of logic to get to the point. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose, then.

I find Miucin a fascinating character. Like all great villains he is cold, detached and uninterested in adhering to our fragile social mores. But he’s also chaotic and destructive. He didn’t set out to disrupt the journalistic integrity of game reviews by stealing opinions. He just re-purposed others’ work and passed it off as his own for unknowable reasons. That’s the mystique of a true bad guy right there.

It’s hard to tell why he walked his dastardly road because he hasn’t offered any explanation. Once evidence of his plagiarism had reached irrefutable status he held strong, blaming coincidence and calling out the internet to find more examples of wrongdoing. The internet of course obliged, revealing he’d falsified almost every bit of content he’d ever produced. Reviews, videos, each and every one of his own actual individual thoughts—nothing was his. Dude even copy/pasted his own LinkedIn profile from a template. Like, why?

Then, with a wave of his cape and a poof of smoke, he vanished, probably back to his secret volcano lair. Filip Miucin had no shame and showed no remorse. It’s not even clear if he ever really existed to begin with.

“Dicked! ‘Ere, dicked? Din’t you read my fookin’ sign, mate?” called out a figure from a distant tower. Even from a hundred meters away, Barristan could see that the structural integrity of the man’s roost was much better than the chapel, which likely explained why it could hold the weight of the massive chain gun the note spoke of. “I’m not triflin’ with you ‘ere, mate, I’ve got a massive chain gun and I’ll totally shoot you with it. What’s that you say,” he began, entirely unprompted, “why’m I up ‘ere threatenin’ to shoot you for no apparent reason? I’d tell you, mate, I truly would, but that’d destroy the ‘ole air o’ mystery I’m attemptin’ to craft. Tell you what. If you can run through this gauntlet o’ monsters an’ gunfire an’ kill me, I’ll let you read the note I’ve stapled to the inside of me cuirass. Then you’ll ‘ave a better idea o’ what’s occurrin’. Sound fair? Gud.”

Not wanting to entertain the games of a deranged Cockney, Barristan dropped off the balcony in front of him, landing on a tiled roof out of sight of the massive chain gun’s ferocious maw. “Barristan isn’t smart enough for the hunt.” They said that too, he just remembered. But they weren’t laughing now. Buoyed by this tremendous outfoxing, he sought out a route down into the bowels of Old Yharnam, which stretched out before him at the foot of a very tall cliff. By traversing the preposterous sequence of balconies, scaffolds, and ledges before him, he would be able to descend three stories in a matter of seconds. Knowing a thing or two about architecture, he noted how fortuitous it was that the time-ravaged buildings had crumbled in just the right way to create a safe path for him. What luck, he thought, as he began his downward scramble.

Landing on a wooden platform sill many meters above street level, he found a small door leading to the upper floors of a tower. Judging from the bells, he surmised it was a belfry. He entered the mid-century Gothic Revival church and began making his way down the spiral staircase. But he hadn’t gone but a few paces before something caught his attention. Peering cautiously through a doorway, he spotted what looked like a man at first, but a second glance betrayed the accursed creature’s true nature. It was a grey, hairy hominid with piercing black eyes, wearing clothes that were all ripped and dirty. What horror lay before Barristan? What madness?! Repulsed and fascinated in equal measure, he slashed the creature three times with his Saw Cleaver. As flesh ripped and bone shattered he thought of his dead parents. This wasn’t the monster that had killed them, but now it was dead they somehow seemed a little more alive.

Continuing down the stairs he encountered another grey monster-man and killed it too, this time not even stopping to marvel at its monstrousness—or giving his parents so much as an afterthought. He exited the church onto a charred cobbled street. It looked like the whole of Old Yharnam had been superficially burned, perhaps long ago, perhaps more recently. It was hard to tell, though, because even as a visitor to the wider municipality of Yharnam, he knew nothing of the place, or even the hunt he had so long wished to be a part of. It was as if any and all supplementary information was being withheld from him for some perverse reason. But not a moment into ruminating on this devilry and his attention was led, quite deliberately he thought, to more pressing matters. There was a werewolf standing just to his left.

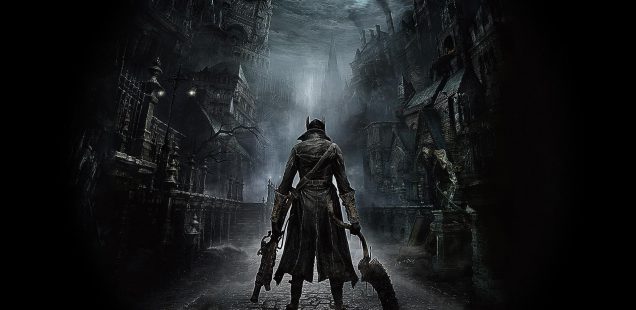

I started quite strong with Bloodborne. After carefully picking my way through a starting area that’s designed to give cocky newbies a near-impossible time, I beat the game’s first boss on my inaugural attempt. Shaking and drenched in the sweat of genuine achievement, I hit up the forums to see what everyone else thought of the Cleric Beast.

I was heartened and surprised to find that many players had found it tough to beat. Smacking the Beast with my funky Saw Cleaver a bunch of times and using a lot of health potions was just about the only strategy I’d needed. But others had struggled with its voracious attacks, their fragile character’s low health, and poor damage output from weapons. Turns out I’d just lucked my way through the fight, really.

As is often the case with the internet, responses to people having difficulties varied wildly. There were kind hearted souls offering advice. Detestable braggarts sharing their flawless victories. Players with beginners luck, like myself, who only later realized the chagrin others faced during the battle. And plenty, plenty of ingrates chuckling at their own flawed imaginations as they whispered the words “git gud”.

“Git gud. Ha hah haha ha hah ah ha hahahahaha. It’s that simple. Hahahahahah.” No. Bloodborne, and I assume by extension the other Souls games—I haven’t played them—aren’t the fabled ultimate form of vidyagamez some elitist internet gross boys have had me believe. They are action RPGs that demand concentration from players—or just enough luck to make up for it—nothing, nothing more.

If anything, Bloodborne follows a very standard RPG progression curve if you let it. I level up. Enemies get easier to kill. That bit of the game gets easier. I play it a few more times and grind out levels. I kill the Blood-Starved Beast, Vicar Amelia, and the Shadow of Yharnam on my first go. In my playthrough I haven’t really gitted gud, I’ve just played in a way that’s made the experience gittended easier.

The game actually has a very organic, accommodating approach to managing difficulty. Innately skilled or at least dedicated players can study its mechanics and hone their abilities, to the point where it’s possible to see the end without ever leveling up. Conversely, those like myself looking for an easier time can instead spend hours levelling up, lowering the overall difficulty by strutting around with hella buffed hit points.

Bloodborne is very flexible with how it lets you play. The idea that gitting gudderer is the only way of progressing is nothing more than inaccurate gatekeeping nonsense. So there.

The werewolf looked much like the monster-men from earlier, all grey fur and cold, black eyes, but it was bigger and more dog-like. A big dog monster-man. A werewolf, essentially. Barristan gagged and watched, aghast, as it stood still in front of him, its back turned. He waited for what felt like an eternity, anticipating an attack. And yet the beast stood as frozen as the never-explained statues that littered Yharnam’s streets. Becoming impatient, he took the initiative and lept towards the werewolf. Four slashes this time. The werewolf was bigger than the monster-man so it made sense it took more hits to kill it. Still, not as many as he’d expected given its terrifying appearance.

His jubilance was cut short when, a little further down the street, he saw two more were-devils. Sprinting towards them with Saw Cleaver outstretched, he readied himself for battle. But just as he was about to engage them his confidence evaporated like blood on a bonfire. From behind the werewolves, three monster-men came running right at him. Their incessant chattering harmonized with the wolves’ growls, scoring the scene with a chilling cacophony. Perturbed but determined, he stood his ground and then swiftly maneuvered around them. Slash. Roll. Slash. Slash. Big slash. Slash. Dead. He’d won.

Doubling back on himself he headed for an alley opposite the church. It was a dead end. As he turned to leave he glimpsed a most curious sight: a werewolf fell from some unknown vantage point and landed at the entrance to the alley, blocking his path and guarding his escape. He killed it. Four. Slashes. And. Dead.

Pushing further into the murk he rounded a corner and came face to face with a screaming wall of smoke. Further investigation showed it to be a trick. It was merely a screaming monster hiding behind a wall of smoke. This one wasn’t hairy, rather a tall, gaunt figure wrapped in a cape or sack. It had red eyes, not black, and let out a wheezing growl from somewhere deep within its decaying body. Unsure of what else to do, Barristan killed it before it ever had time to attack. Nearby, he stumbled into another werewolf and killed that too.

As he returned to the church and ascended the tower, his chest burst with pride. Five monster-men, five werewolves, and a screaming sack. What a night. What a hunt! Leaving the tower he ran along a scaffold and climbed a really, really long ladder, finding himself back outside the crumbling chapel. Striding over the mad Cockney’s note, he smiled and let out a bellowing laugh as, all at once, he remembered his dead parents. “You see, ma and pa, I’m a hunter now, just like I promised. It’s almost like you died so that I should live, live my fullest life. Ha ha ha. Ha ha ha. Ha ha—” His laughter continued to echo around the derelict chapel long after he’d returned to the darkness of the stairwell.

I ran the Old Yharnam level dozens of times, killing those same 11 monsters over and over again. That’s why my story about it is so good; the prose, characters, and imagery so vivid. Along the way my ability to play the game of course improved. As I learned enemy attack patterns and animations, I became better at knowing when to strike, and more importantly when to hold off. I also became intimately familiar with the level itself, which let me move around enemies and attack from the safest angles. But these learned improvements are nothing when compared to the statistical ones I gained by overleveling Barristan Selby. Yeah, I got better, but I was staying alive longer and killing stuff more easily. Of course I got better.

The chin-chewing discourse surrounding the Souls games in some corners of the internet put me off playing them for years. I was told they were hard and complex, unforgiving and obtuse, meant only for the most dedicated of players. They aren’t, or at least Bloodborne isn’t. Patience and a willingness to learn from mistakes are all that is required to have a good time. Which I am. I’m having a really, really good time with Bloodborne.

The git gud mentality—whether used sincerely or with a sardonic sliver of faux benevolence—is exclusionary, yes, but it’s also baseless. Bloodborne doesn’t have to be something genuinely skill-based like, say, DDR, Ikaruga, or crochet if you don’t want it to be. Yeah, you can do a no levelling run or something fascinating and mad like that, of course you can. But for someone less serious, playing the game once like I am, progression is possible if you take things slow, play mindfully, and, when in doubt, grind mad Blood Echoes and level up some.

So where does this oversimplification spill forth from? Demon’s Souls and the original Dark Souls were mysterious entities upon release; just go back and read reviews to remind yourself of how they perplexed and enchanted people. Over the years, though, their deliberate obnoxiousness has been unpacked and charted, and sequels have further demystified the series. We now know that the games aren’t difficult in a conventional sense, rather they demand care and attention from players and a willingness to learn the pretty specific way of playing them “properly”. The Souls game’s aren’t the enigma they used to be—even I know how to enjoy them, thanks to years of osmosed knowledge I never asked for.

But the internet, o’ land of memes and ill-conceived hot takes, whose collaborative spirit cast its light into every one of the Souls’ murky crevices in the first place, ruining the mystery for everyone, perpetuates all. Copies of copies of copies, images disintegrating into compression artefacts and overlaid banter captions. Idiots repeating idiots repeating idiots who were “just using satire” all along. The world on fire. Bloodborne might not be that hard now we understand the series’ logic, but someone somewhere, before we knew any better, once said Demon’s Souls was super difficult, so the story must still wash to some extent, right? This is the flawed logic that underpins and perpetuates the cries of git gud, and in turn the larger cycle of reductive second hand internet knowledge that repeats ad infinitum.

Filip Miucin is an indirect product of our hellscape of collective wisdom; a place where information—whether it be accurate or not—is passed down through accelerated generations of internet users, remixed, altered, amended, and ultimately born again entirely. If the internet contains everything all the time, and most of it can be rearranged and rebuilt anew, how can any of it truly matter? Who owns a gif, a meme, a four panel comic strip? Nobody, and yet everybody. Thanos in a film still becomes Thanos in an Old Spice commercial, becomes Thanos in the This is America video, becomes Thanos at the Trump inauguration, becomes Thanos in the American Chopper meme. Internet culture is an ever-evolving collage of signifiers and shifting meanings. Trapped by this uninterrupted (and often nonsensical) overload, we’re all to some extent cultural nihilists whether we wish to acknowledge it or not.

Miucin took the work of others and made it his own because that’s just what we do now. He was so brazenly unapologetic because he didn’t understand, couldn’t even fathom, how it could be a problem. And when pastiche and iterative reproduction are common currencies in online discourse, can we really blame him? “Kotaku are running stories on me for clicks, [not because I stole all my work],” is such an idiotic thing to say, but it’s also guileless in a very 2018 way, just like his notion that “all writers read the internet for research before forming opinions.” Some of us don’t. Some of us write narrative-based criticism expressing our thoughts on a game while simultaneously dissecting the culture around it—and you can’t steal that. Admittedly, all these thoughts have undoubtedly been thought and expressed by other thinkers before me, I just haven’t come across them to mine for inspiration. (Honest.)

Plagiarism is obviously wrong, and knowingly partaking in it should be punishable by a most horrible death. But Filip Miucin doesn’t deserve to be put down as a plagiarist any more than I do as a future Pulitzer Prize winner. He isn’t a bad guy and he doesn’t live in a secret lair, volcano-based or otherwise. He’s just a bloke who misread the room. The world told him to git gud and he responded by curating, repurposing, and synthesizing. In a word: the only way he knew how.

Leigh Harrison lives in London, and works in communications for a medical charity. He likes canals and rivers a great deal, and spends a lot of his time walking. He occasionally says things about videogames on the Internet, and other things on The Twitter.