Due Diligence: Blocky Horror

Leigh Harrison forgets what he came here to do.

Cuts. More specifically, jump cuts. Crime caper 30 Flights of Loving implemented them to great effect, and in a style familiar to how they’re used in cinema. Its cuts quickly articulated a passage of time, chopping the narrative into confusing non-sequential vignettes. One minute your character would be in a warehouse at sunset, the next, an airport having breakfast. Everything in between was inconsequential, and as a consequence you never saw it. But was that tomorrow’s breakfast…or yesterday’s? You never really knew. Paratopic is a first-person horror game. It has jump cuts too, and along with moving the story on at a good clip, its are also used in inventive, unsettling, and sometimes darkly comedic ways.

I’m one of the game’s three main characters and I’m waiting for an elevator. It takes 30, maybe even 60 seconds to arrive. I can see it slowly descending through the shaft, grinding its way down towards me. When it arrives, the doors peel themselves open in painful, deliberate spasms. This elevator is wheezing before me. As soon as I enter, CUT, I’m already at my floor. The cut does its job propelling you forward in time, but the excruciating build up also makes it a thing of slapstick brilliance. And coming so early in the game, it also utters a warning: unlike 30 Flights, it will take the language of cinema (and your understanding of it), and twist it beyond recognition. This is a great jump cut.

The game’s visual treatment is that of Deus Ex stuffed inside of Silent Hill. Diners, gas stations and apartments are low poly, draped in sparse, blocky textures of dirty browns, reds and greys. As if the rust and blood of Silent Hill were all too gauche, too obvious, Paratopic’s places just look uncared for and shabby. This is urban isolation in all its miserable glory. In roughly hewing its world from such monolithic slabs of level geometry, the game’s locations are so vividly relatable. I’ve stood in shops that look like Paratopic’s. The hallway at the top of that elevator ride might as well be the one outside my north London home, such is its nondescript banality. The game’s lack of discernible visual detail leaves a void I’m all too willing to fill.

I’m stood on a pitch black highway. There’s a car pulled into the roadside, its headlamps shooting cones of light a little way off into the emptiness. They don’t make me feel any safer. I search around in their glow, trying to make out shapes in the distance, perhaps an oncoming car. Nothing. I swing around to the trunk and grab for the camera I find there. The instant I do, CUT, it’s morning. The power of this cut is in its seamlessness. Jump cuts tend to move you through both space and time, whereas this only does the latter. It’s one fluid movement. You’re reaching for the camera. It’s night. You begin picking up the camera. It’s morning. You finish picking up the camera. This cut is so simple, yet is breathtaking in the elegance of its execution.

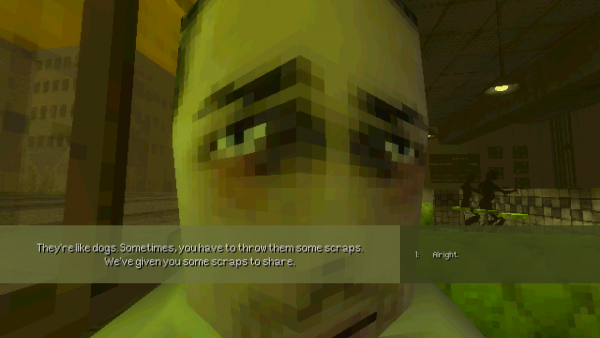

Paratopic channels Deus Ex in its working faucets, flushing toilets, and character models. I don’t remember anything about the bodies; they aren’t all that important to the game (outside of a shocking jolt of on point body horror). Heads are roughly ovoid shaped and painted with flat, expressionless faces. Eyes are sad, tired, and vacant all at once, emphasizing the sense of deep humanistic despair that permeates the game. Its roughly connected stories are ones of marginalization, of anonymous people nobody cares about doing things they probably shouldn’t. I don’t know why these characters find themselves marching through the woods, or smuggling video cassettes, or murdering diner employees. I get the impression they don’t either. So while a Bad Man’s face contorts and warps around his head in Cronenbergian grimaces—which is deeply unsettling—it is the folornness of the supporting cast that leaves the lasting impression.

I’m doing something. Maybe I’ve just left a room. Maybe I’ve just taken a photo of a bird. I don’t remember; the details are hazy. Whatever I’m doing, at some point I’ll stop doing it and, CUT, I’m in a car. Now I’m driving. It’s dark and the road is empty. I can see maybe two or three meters in front of me, only as far as the headlamps are willing to illuminate. I steer ever so slightly every so often. Beyond that, all I can do is stare ahead and listen to the radio. For about five minutes. The cuts to the car—the scenes recur throughout the game—are sublime. They upend the jump cut by cutting you into something that would normally be cut out, whilst also cutting into and then back out of what is undoubtedly, temporally speaking, a much longer sequence. The scenes themselves are also truly captivating. As you peer out through the windshield, transfixed by the darkness, you’ll swear you see things dance across the road. You’ll lean into your screen a little to get a better look, but whatever it is is always just out of view—if it was ever there to begin with. You eventually leave the car, but its tension never subsides.

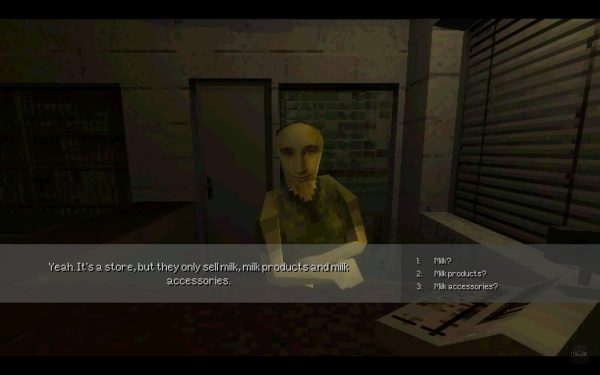

At a truck stop I talk to the proprietor. He knows all about the local area. The pancakes down the way were the best in the country, before the place burned down. There’s a giant ball of twine that’s a hot tourist attraction, and the milk store is not to be missed. (A milk store sells milk, milk products, and milk accessories, by the way.) Another time we discussed theology and its intersection with extraterrestrial life: does God exist, and if yes, are aliens just angels?

The cuts to the truck stop—these scenes also recur throughout the game—offer Paratopic’s only instances of non-confrontational human interaction. What’s more, unlike branching dialogue in most games, these strange and funny conversations never have to end. If the characters keep repeating questions, the proprietor will keep repeating answers. This circularity heightens the humor, but also further amplifies the dread waiting outside the gas station walls. Like stilted small talk used to fill agonizing silences at a party, these scenes belie our innate need for human interaction. Hell might be other people, but if it’s that or being alone, I think we all know which one we’d rather.

I don’t know if Paratopic is about anything specific—though poverty, depression, and loneliness would all be valid candidates if it were. (The imagery of a man being flayed alive by a TV screen certainly points to isolation in the digital age being a preoccupation.) Regardless, there’s power to this ambiguity. While the game at first appears to be a grab bag of novel moments, they all eventually come together into a deeply moving experience. The jump cuts and forlorn characters. The protagonists’ lack of discernible purpose. The unending boredom of the highway. All are pointed distillations of our daily struggles. Paratopic is a parable about our anonymous, fractured lives, and how hard it can sometimes be to simply get by.

Leigh Harrison lives in London, and works in communications for a medical charity. He likes canals and rivers a great deal, and spends a lot of his time walking. He occasionally says things about videogames on the Internet, and other things on The Twitter.