Art Tickles: Starting Line Cinematics

Taylor Hidalgo plays from a theater seat.

An empty, vacant soundscape resolves to the sound of rushing air. The camera starts on a tight angle along the side of an old military plane. It follows the line of an airplane’s body, as though flying in its slipstream. As the camera draws back, the view quickly dips down through the empty space where the tail of the plane would be. We discover that the old shell of this military bomber is sunken into the dirt. Unpaved road slides into view, which the camera follows until a bright red sports car rips across the frame.

The sound of sirens picks up from the vacant soundscape, quickly followed by the roar of engines. A few visible fractions of police cars fly by in pursuit of the sports car. The radio picks up, and the camera rushes past the squad cars toward the tail lights of the sports car before locking onto a familiar third-person view. The car races through the hollow shell of the sunken bomber, and the player resumes control. Energetic dance music thumps merrily into the late afternoon light, sirens scream, and the player flees pursuit.

Every mission opens with its own string of visuals like this. They’re precursors to the 2012 Need for Speed: Most Wanted’s scripted races, pursuits, and chases. They are purely cinematic, designed to evoke almost contextless senses of movement. Energetic pans, swooping motions, sharp changes of colors, surrealistic imagery, and sudden cuts all serve to build a pace that keeps the player sufficiently charged to take part in whatever high-speed carpocalypse is queued up. Moreover, they each provide a moment of respite.

The radio, an omnipresent fixture while blasting through the streets of the fictional city of Fairhaven, thumps and rocks as players drift precariously around corners. The high-volume growl of music makes the city’s streets feel all the more packed with energy. Speed cameras line the roads, keeping score of the player’s max speed, comparing it to their friends’ paces and goading them to hurl themselves with reckless haste around again, just to clock slightly faster numbers. Gated areas, ramps, and breakable billboards all litter the sidewalks and rooftops, begging the player to carve wild shapes across the city with their burnt rubber.

When the player skids to a halt at a mission marker and spins their wheels to start the mission, the radio goes silent. The world dissolves to a quiet loading screen, and what follows is cinematic decadence. Compared to the wall of sound that normally follows the player, that of the noisy radio and the fury of powerful engines, the vacant soundscape seems utterly silent. The camera puts the player in the seat of an audience member for a moment, and takes them on a journey. The flex of suspension straining against gravity bounces a pack of cars jouncing gracefully over curbs, and the thick concrete whumps with a distant bass as the camera whips past columns. Texture bleeds into color as the sky and road trade places. A racer drifting sideways around a corner leaves afterimages as it passes, only for the car to rewind through time, and the afterimages drive in, merging with their source vehicle.

A beat as the car sits frozen on the road, as if the entire city is taking a breath.

And then the race starts in earnest, the radio flares back to life, the racers scream in from the background, and the player resumes control. Blue fire spits from the tailpipe, and the speedometer climbs.

As enthralling as this sense of momentum and speed is, there is something distinct about the cinematics that precede missions. It’s an artist’s rendition of waiting on the racing grid: a respite from the chaotic velocities, a few deep breaths, and then the mission starts.

Personally, I find myself recoiling at the idea of a “cinematic” game. Some voice deep in my subconscious, likely one formed from many years passively taking in arguments from the game community, insists that cinematic is a dirty word in games. It insists that being captivated by a game for its passive experiences is wrong. What makes a game unique and effective, arguably, is in interactivity and leveraging aspects specific to the gaming medium. So, in theory, games that lean too thoroughly on cinematography should ring a little hollow. In a way, I feel like that voice buried in my mind is leading me to a spectacular crash, over something as harmless as some cerebral visuals. Screw the voice, no point in denying the cutscenes are the best part.

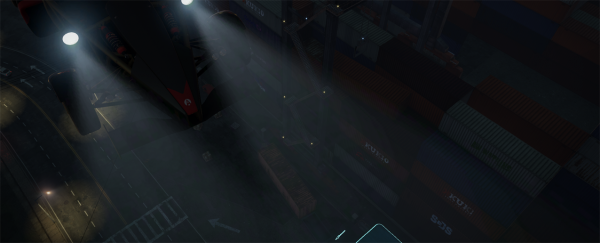

Although I really jam to the high energy drive of racing through busy streets with the radio pulsing in my ears and the engine echoing from the bricks, I find myself craving the more conceptually interesting journeys, these lavish and abstract cinematics. The proverbial calm before the storm feels so much more unique and iconic to me than all the fury of engines and bright hazards of oncoming headlights. For however good the racing is, I get so much more from a surreal tableau of police cars, strobes alight in an authoritative fury, driving on all surfaces of a rusted over industrial space. The chase of twenty police cars that stalk along the walls and ceiling of a narrow, grated industrial corridor. The tour of an iron factory shifted an unnatural red. Rust painting abstract art on the shipping containers stacked against the walls. A tour of a suspension bridge from an ant’s eye view, the sunlight blown out into a polluting blanche white that spills over the edges of black cables and bleached concrete. As beautiful as Most Wanted is for most of its play, few big budget games are as willing to be as visually decadent and utterly surreal as the visuals that precede its missions.

I’m already dreading the moment the camera closes back in. The distant sounds and dreamy visuals coalesce into normalcy, and I can feel the cinematic coming to a close. I jam on the accelerator in anticipation of regaining control. Then the engines unleash their fury, and I’m back behind the wheel.

Taylor Hidalgo is a writer, editor, and Features Editor here at Haywire. He’s a fan of the sound of language, the sounds of games, and the sound of deadlines looming nearby. He sometimes says things on Twitter, his website, and has a Patreon if that’s your thing.