Art Tickles: Putting Out Gunfire

Taylor Hidaglo is frightened by the intersection between time, art, and death.

Super. Hot. Super. Hot. Super. Hot.

I love guns. I do not like guns. They are fascinating. They are terrible.

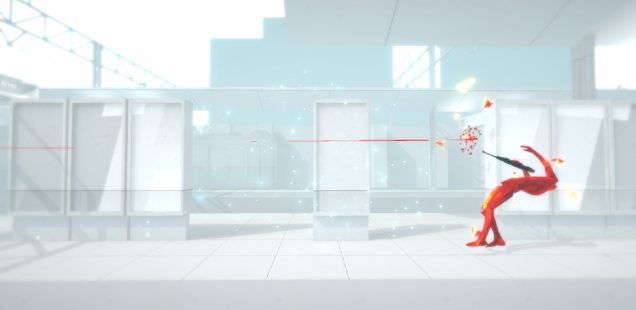

This world is beautiful. Muted whites and sharp reds surround me as I fight. Stained glass bodies in constant motion make me feel like I’m observing the collision of installation and performance art, as though gunfire is ringing through the blank halls of a museum. I stand here, in place, observing the art move in a quagmire of time, the visual atmosphere seemingly cooling down as the motion stills, ready to explode back into a frenzy with just a footstep, or a glance in a new direction.

I am drunk on the stillness. The painfully temporary moments of inaction. When I do not move, time slows to a barely perceptible crawl, but it still crawls. As I explore the room, taking in the striking vignettes of glass and motion, time is crawling forward. Gunfire draws veins of threatening red lines in the sky, illustrating danger that glides gracefully through the air. Any of these trails may very well shatter me, a being even more breakable than the red figures.

Super. Hot. Super. Hot.

My biggest frustration is that this world is aesthetically fulfilling. I want to just sit and watch it for a moment, distinct from the sense of action. I’ve fallen in love with the serene but deadly performance that seems to swallow me whole. I feel like I’ve found a piece of art that resonates with me, but I love only half of it. The graceful movement speaks to me, but the violence that follows stings. I do not want to shatter these still frames. I’d prefer to observe, explore their movement passively. The longer I take to do so, the more likely I am to be shattered, forced back to the beginning. This art has a fuse.

Before it bursts into action again, I step to see a new angle, but the bodies of crystalline blood are coming for me. The black shapes in their hands threaten me with cruel edges, thick bludgeons, and blooming muzzle flashes. They are coming for me, and my only way to explore the next gallery is by taking the hammer to this one. My window into this world relies on efficiency of survival, turning the art into a series of hurdles. I do not like looking at it this way.

I don’t want to do this. But my obsidian fists fly, I step between the deadly trails, I destroy the red glass throughout the room, leaving temporary fragments of the art remaining on the ground, if at all. I’ve killed the glass men who were coming for me. The explosive shards of my foes have their own sort of artistry, like a firework. I don’t want this experience to only be a few seconds of bright colors, but I cannot experience it again without having to break another sculpture. Super.

Hot. Super. Hot.

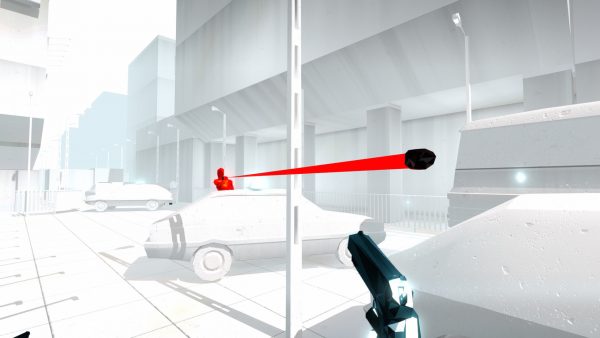

I wish that so much of this medium wasn’t predicated upon violence. I find myself wanting to enjoy this game in a way it probably wasn’t meant for, but easily could have been. I don’t want to kill these glass men, to destroy the spectacle of their motion, but I’ll die and live and die forever if I don’t. I keep coming back to these guns we’re all holding. They’re interesting, and I love to watch the tactile pathways they design through the rooms. I love listening to the thump-drawl of the propellant snapping the bullets forward, and then slowing to a crawl as I watch the trails and contemplate the next few seconds. Which angles will be safe, which unsafe, which angles should I shoot into, which should I lance my weapon into, how long until I’m set to fire again, how long until I’ll be cornered. Fractions of time slowing to a humming stasis as the bullets sing—then drag—across the air. Or if I’ll shatter from an angle I’ve missed the next time I take a step.

Even if these are mentally fulfilling puzzles for me to trial and error, leaving shards of blood-colored glass on the ground until my fragile body joins the asphalt and the entire exercise restarts from the ground up, I still long to get to experience SUPERHOT in a non-violent way. A way where the violence stops being the goal — to indulge in how these intersecting angles and convergent colors behave in this white space. What would this be without clubs, swords, and guns? Hot.

Super. Hot. Super.

I always find myself failing to draw meaningful conclusions with my relationship with guns in the wake of real-life gun violence. Outside of fiction, outside of games, where the explosive roar of weapons comes with a literal body count. A place where violence is far more contextual, where gunfire is meaningful both for the immediate victims and the aggressors, but also beyond intended context.

In my experience, guns are a sort of equipment. I pay attention to what sort of ammo is the least failure prone with my weapon so it’s safer to operate in a range setting. I enjoy getting to extend targets to longer distances and steady my breathing, focusing my attention on lining up three little dots. Getting to see the fruits of my effort reflected on a piece of paper swinging downrange feels validating. Controlling little explosions toward a specific goal while following the necessary safety steps is fun. Target shooting is fun. Knowing the mechanics of my little pistol, and knowing those mechanics allows me to take an active part in the weapon’s maintenance. It’s a fulfilling diversion, and a skill that makes me better appreciate just how neat these plastic and metal beasts are. Guns are cool, both functionally and technically.

Guns are tools, and sporting equipment, but they’re also weapons. They also kill.

Games can’t be entirely divorced from life. These weapons are at-times exacting recreations of the physics and mechanics of real firearms. The characters and player avatars live and die by similar rules to flesh-and-blood bodies outside of the fiction of in-game universes. Those of us who both play games and own guns find part of our internal vocabulary shaped by the way guns in games are good for just one thing: killing. It’s a context we’re constantly submerged in, and one I struggle with.

I’ve written elsewhere about how games perhaps retool the way we think about overcoming obstacles, and as someone who owns and maintains a gun for the purposes of target shooting, I often think about the way digital guns and my literal, physical one interface with one another in my mind. When I hear noises in my home I cannot identify, I have to suppress an impulse to grab the gun as the problem-solving tool. As though any possible source of that noise should require a deadly force weapon.

I don’t know if I have a fix for that, or if I’m personally challenging the way games encourage me to make these mental pathways. It’s possible that I don’t challenge my enjoyment of these games enough. I don’t know if I have any answers. It’s possible that in having these questions, I’m taking the appropriate first steps. It’s possible that I’m overthinking.

It’s easier to mull over these thoughts in context of a game in which I value the visual and sensory aesthetic. In a world where violence is only disrupting my experience, rather than disrupting people’s lives. Easier to wonder if the ways I enjoy owning a gun is worth the risk I could bring to myself by having it in my home.

Taylor Hidalgo is a writer, editor, and Features Editor here at Haywire. He’s a fan of the sound of language, the sounds of games, and the sound of deadlines looming nearby. He sometimes says things on Twitter, his website, and has a Patreon if that’s your thing.