Opened World: Kentucky Route Zero Act II

Miguel Penabella shifts his gaze to the intangible.

This is part two of a comprehensive overview of Kentucky Route Zero. See also: Part one, part three, part four, and part five.

Four months separate the release of Kentucky Route Zero’s first act from its second, and if developer Cardboard Computer keeps its word that the final act will surface this year, it will have been five years since we first started this journey. I don’t mind the long intervals between acts; this slow wait, like an extended intermission or an unhurried dream, is part of the experience of playing Kentucky Route Zero. Your memory of the previous act will have become hazy over many months, though the action of the game picks up mere minutes after we last left off. Temporal incongruity between player and character adds to the game’s dreamlike quality and is reflected in its characters who lack a definite sense of their bearings and history. Amanda Lange briefly discusses this abstraction of time, comparing the long nighttime odyssey of truck driver protagonist Conway—further lengthened by the interludes and drawn-out development time between acts—to the nostalgia of summer nights and the accompanying sense of time lost while waiting for dawn. In numerous ways, this game is principally about the passage of time and its effect on space, exploring the economic toll of unpaid debt; the decay of bodies; the gradual disappearance of places; and the weight of history in the South.

In my examination of the first act, I characterized the game’s portrayal of the South as a “palimpsestuous layering of mismatched histories,” a folkloric re-imagining of Kentucky. Act II’s first scene in the Bureau of Reclaimed Spaces similarly collapses the real and unreal, the past and the present. Shannon, Conway, and his dog arrive at the foot of this six-story concrete office block, which sits inside a massive cathedral alongside a river. Hermit crabs, a docked boat, and a fishing rod adjacent to running water obscures the line between interior and exterior spaces. There is no doorway or threshold that separates the outside from the lobby of the Bureau, and the boundaries of the building remain unclear, as though the building were only half-constructed and open to the elements (an entire floor is inhabited by bears). Why is a modern office building situated inside an ancient, rotting cathedral? In this opening scene, the game invokes a sense of “imagined architecture,” directly referencing (via the text) philosopher Gaston Bachelard’s book The Poetics of Space. Cara Ellison examines Bachelard’s influence on the game, noting how Kentucky Route Zero is similarly invested in the notion that inside and outside (and other binary spatial choices) is an unimportant distinction. Rather, the individual’s phenomenological experience of a space is the paramount question for architects—and by extension, for videogame level designers—in which a structure serves as a vessel for human consciousness, and more importantly, as a storehouse for dreams and the imagination.

This interest in interweaving histories and emotions into spaces also reflects the game’s indebtedness to mid-century stagecraft, such as Jo Mielziner’s 1949 production of Death of a Salesman. Mielziner designed a skeletal framework that sequestered spaces, allowing the past and present to coexist onstage. The exposed brick of New York City tenement apartments intrudes upon the wallpapered domesticity of a bedroom, allegorizing the emotional and historical entrapment of protagonist Willy Loman as he suffers the burden of personal failure. The concrete and brick Bureau of Reclaimed Spaces soars toward the stalactite-studded ceiling of the cathedral that encloses it, similarly coalescing the interior and exterior world. But while Death of a Salesman’s production focuses on individual economic entrapment, Kentucky Route Zero’s spatial ambiguity suggests how economic downturn can result in broader real estate shifts as tenants are displaced or foreclosed, leaving behind vestiges of their presence.

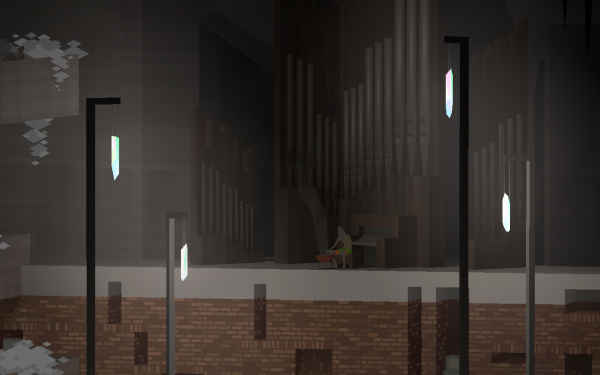

Within the Bureau, we meet the artist-turned-office drone Lula Chamberlain as she reviews forms that approve the repurposing of old, likely foreclosed, buildings (hence: reclaimed spaces). A hospital awaits repurposing as an auto dealership; a basketball court to a kennel; and ominously, a distillery to a graveyard. The office itself is evidence of this reclamation effort by the Bureau, and its surreal mishmash of styles is indicative of tangible economic crisis. The cathedral once housed the congregation of the Saint Thomas Church, but their numbers have since dwindled after being evicted to the Random Access Self Storage facilities. Only audio recordings of a sermon remain, broadcasting to an absent crowd. In visualizing the decaying architectural and social infrastructure of the South, the game conveys its Southern Gothic influences. While the Southern Gothic typically unpacks the social and cultural character of a crumbling South via macabre stories of a maddened and sickly aristocracy, Kentucky Route Zero presents scenes in which the magical and mythic casually coexist with the utterly mundane and familiar, rendering a South seemingly dislodged from time. At the Bureau, histories collide: the office building may be a modern, Brutalist skyscraper, but climb up to the mezzanine, and Conway can discover a massive organ left over from the old church. This is a residual space, in which the ghosts of previous occupants linger on, with all their historical baggage.

Such spectral themes and images are further explored in the Zero, a dark, wireframe roadway spangled with strange, sinewy iconography that serve as mythic referents of the South, such as a scarecrow, telephone poles, or deer antlers. Whenever the Zero is brought up in text, a cloudy filter is overlaid atop the word, suggesting the location’s unreal, spooky quality, a typographical choice examined further by Leigh Alexander. Traversal on the Zero operates via an abstract, dreamlike logic, as though motorists were plunging into a vortex. Players control a wheel circling around the Zero’s loop, crossing paths with the aforesaid roadside markers. These landmarks signify places where players can reverse the wheel’s direction—as though following rudimentary directions such as, “Make a U-turn at the crystal”—to reveal previously hidden locations. This oscillating movement through space in what’s ostensibly just a simple loop thus takes on the form of a padlock, in which one must advance and backtrack in order to unlock the Zero’s secrets, like the railway turntable of Act I’s Elkhorn Mine. Kentucky Route Zero emphasizes a sense of circularity, gesturing towards broader themes like the cyclical nature of time. Rather than move forward on a straight line or in a teleological model of history, we must double back, returning like ghosts to places we’ve been. Indeed, the wireframe walls of the Zero remind me of the belly of a snake, evoking the eternal return of the ouroboros, endlessly cycling and re-creating itself.

Kentucky Route Zero constantly plays with this precarious relationship between time and space, leaving both characters and players uncertain of their bearings. When Shannon, Conway, and his dog step foot in the Museum of Dwellings towards the end of Act II, our perception of an interior and exterior divide is again called into question. The trio wanders the exhibits, viewing various dwellings on display, including a tent, camper, birdcage, chicken coop, etc. housed within a massive warehouse. The camera is positioned high in the warehouse’s rafters, partially obscuring our view. Like surveillance equipment watching from above, our perspective is voyeuristic, and the narration during this scene comes from Museum staff reporting on the demeanor and conversations of the protagonists in the past tense, thus casting this entire scene as a flashback. This strange narrative framing renders it more difficult to pinpoint the sense of time and space as Conway and his companions travel deeper into the Zero and retreat from reality, disappearing into this nocturnal dream world. At one point, museum staff member Flora narrates her observations of Conway as he explored the cabin exhibit. She recounts Conway’s discovery of the building’s nonexistent basement, which he can find by digging into the ground with his bare hands, revealing the impossible space of an underground river and garden below. This ease with which the game slips into dreamlike temporalities and spaces beyond the bounds of possibility mirrors the casualness with which people can easily disappear into their own predicaments. Weaver disappeared in the last act because she can’t pay her debts; the submerged Elkhorn miners lie trapped below the Earth. The sequence’s detached point-of-view and emphasis on personal recollection exacerbates this dislodgement from reality, turning characters like Conway into a ghostly memory half-remembered.

Act II ends with a final march through a forest with new companions Ezra, a kid abandoned by his parents; and Julian, the giant eagle that watches over the boy. Accompanied by The Bedquilt Ramblers’s sorrowful folk twang, the characters progress deeper into the woods via a series of elliptical jumps forward in time. Parallax scrolling bisects the landscape, creating an illusory effect like René Magritte’s painting Le Blanc-seing as landscape, forest, and objects are impossibly sliced and interlaced together. As Ezra and the dog walk forward to the right of the frame, they recurrently pass by Conway and Shannon at different resting sites along the walk, suggesting the expedited passage of time. “These woods go on forever,” remarks Conway, leaning up against a tree, his leg aching after injuring it down in the Elkhorn Mine. As Kentucky Route Zero tasks players with new and surreal ways to travel through its world—parallax scrolling through the evening thicket, soaring above the map on Julian’s back, advancing and reversing on the looped Zero—Conway decelerates, slowing his gait as his body deteriorates. Evoking the work of Flannery O’Connor, who deploys external infirmity to represent internal character, the game allegorizes Conway’s injury to signify the weight of financial and interpersonal impositions. For a deliveryman, mobility equates to livelihood, and this leg injury means mounting pharmaceutical bills newly owed. While the game overlays the histories of a decaying South in a single space, what remains constant is people like Conway—and Julian, and Shannon, and Weaver—falling on hard times.

In future installments of this comprehensive overview of Kentucky Route Zero, I’ll be examining the poetic writing style and narrative approach of the game, and Act III’s juxtaposition of the sublime and the mundane.

Miguel Penabella is a PhD student investigating slow media and game spaces. He is an editor and columnist for Haywire Magazine. His writing has been featured in Kill Screen, Playboy, Waypoint, and Unwinnable, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.