Sowing Dread

Francisco Dominguez asked Dan Pinchbeck to shine a light on the murky depths of A Machine for Pigs.

It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied – Jeremy Bentham

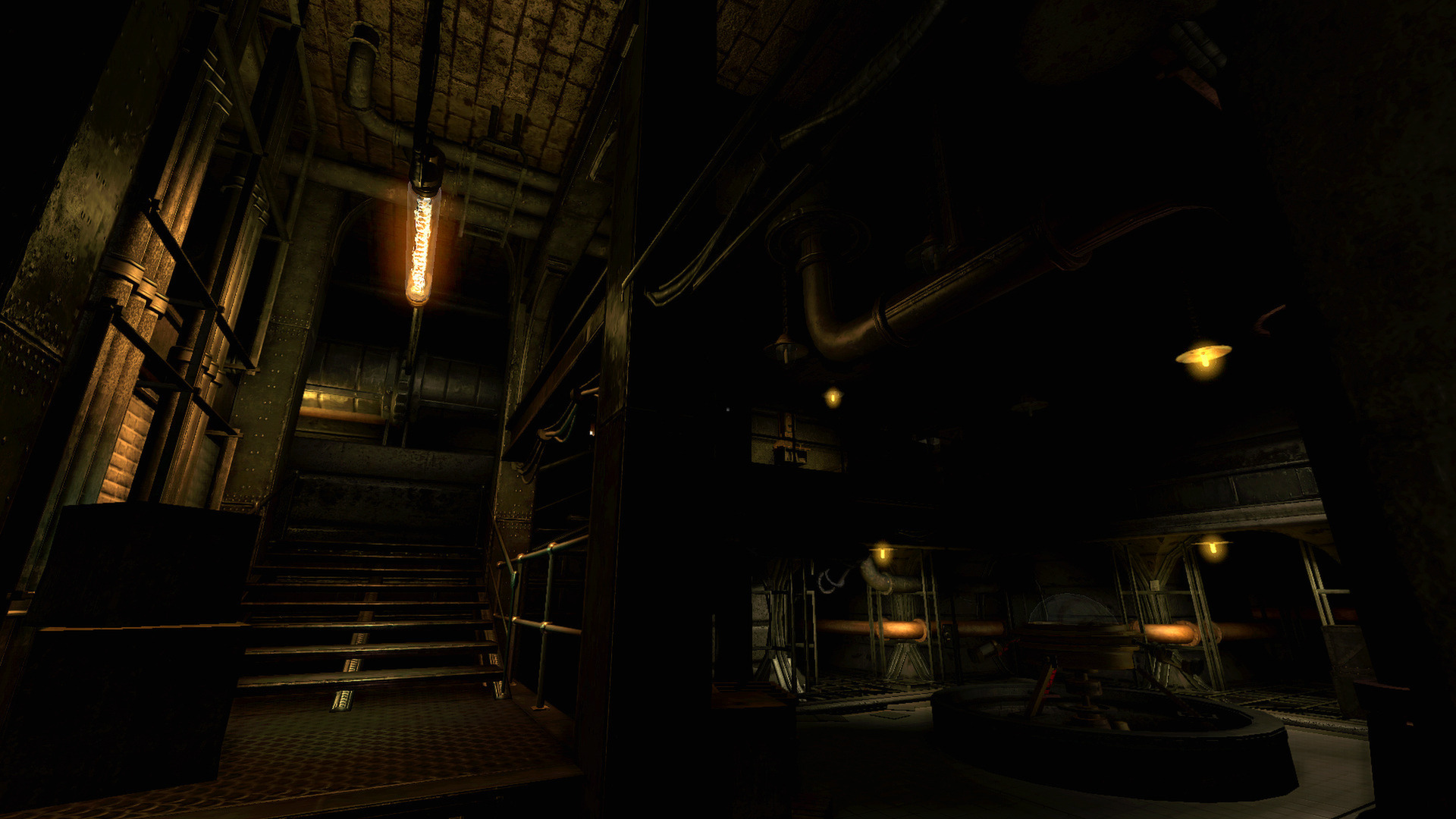

Victorian London has become an easy fit for horror. With its urban areas characterized by claustrophobic industrial cityscapes, their smoggy nighttime streets barely pierced by inadequate gas lamps, the setting is an environmental artist’s dream. Meanwhile, interiors with creaky floorboards, severe mahogany walls, ominous grandfather clocks and unsettlingly unsmiling black and white photographs all combine for an eerily unnerving atmosphere.

But beyond these well-known sensory touchstones, there’s more to the setting’s culture which is capable of astonishing and appalling us. Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs seemed to reach past these familiar tropes and connect with how Victorians regarded their own rapidly accelerating society. My curiosity aroused, I got in touch with thechineseroom’s creative lead, Dan Pinchbeck (of Dear Esther fame) to cast some light into the murky gloom.

Examining, as we are, the worst of humanity, needless to say: here be spoilers.

Late in the game set in London, New Year’s Eve, 1899, it is revealed that industrial magnate Oswald Mandus’ madness, the resultant murder of his children and that gargantuan apocalyptic engine at the heart of his estate were triggered by visions of the oncoming devastation coming to Europe in the first half of the 20th Century. He sees visions of his children dying in the unprecedented disaster of World War I and moves to spare them that fate.

Claiming that the Victorians had a sense of what was coming would, of course, be unforgivably trite, but public discourse of the time shows increased moral alarmism at where this disorientatingly rapid technological and social transformation would take them. Figures like John Ruskin argued that mass production had a spiritual toll on workers who were losing distinct ownership over what they made. And Max Nordau took the theory of evolution and applied it to culture with what became known as Degeneration Theory. We’ve hopefully grown mostly indifferent to articles linking media to the destruction of desirable values, but the Hungarian social critic wrote five books outlining an incredible socio-medical theory that humanity’s progress was the accumulation of bad decisions, heading towards future collapse.

This idea of a gradually increasing threat ties in both with the actual historical tragedies to come, and how the development of the game’s apocalypse is induced. When I asked about Amnesia’s apocalyptical bent, Pinchbeck responded:

“To be honest, I’m not the most self-reflective of writers, so I don’t want to be pretend I was really clever and forward planning about it. I knew I wanted to just explore those themes, and the idea of evil being this result of small, boring decisions. Rather than a grand, operatic villainy, actually it’s the steady accumulation of ideas and decisions and fear. Somehow we ended up with an atomic clockwork AI and a deranged bastard instead…. But I think what is interesting to me is that Mandus acts the way he does, even if it’s on this fantastical scale, because he’s driven mad by the grief of his wife’s death and, ultimately, the schism between loving his children and blaming them for her death, and that literally splits him into two and creates the madness of the world. So there’s a small scale at the root, I hope, a human heart to the drama.“

What’s interesting is how the pain of a single person ends up leveraging an industrial apparatus to drive a war machine, even against his own will. The pessimistic inevitability reflects Nordau’s theories, and creatives of the time routinely made their reality become a sinister place. Barbers will slit your throat while your baker makes pies from human flesh in Sweeney Todd. Shipping warehouses could smuggle supernatural beings into the country in Dracula.

But uniquely for A Machine for Pigs, we live in the aftermath of its doomsday scenario. We live in the fallen world Mandus couldn’t face. And, from the western perspective at least, is it so bad? Globalized trade makes total war unprofitable, disrupting the relatively settled, mutually beneficial trade blocs we’ve built since then.

In a scene towards the end of the game, the pig-men are unleashed on London. The sounds and imagery of fire and explosions and wrecked buildings evokes London during the Blitz, but the latest explicit reference in the game is the atomic bomb. Talking to Killscreen, Pinchbeck linked the proclaimed utilitarian goals of Hitler and Stalin to more recent travesties in the Balkans and Rwanda, but this progression to modern war never comes through in the game. To me, it was a convoluted case of the present looking back to look forward, but never looking forward far enough to meet its own eyes in the reflected present. And a striking opportunity to implicate the present in the wreckage of the past was missed.

So I had to ask: how can a point possibly be made about modern utilitarian oppression when you pass over the last 60 years? A mass surveillance network or Apple factory may not easily fit into Victorian society, but when visions of the future already form integral pieces of the plot, is ignoring the present acceptable?

“Actually, the inspiration for the game came a lot from the kind of neo-Victorian attitude that is running our country right now, so I do think it’s relevant. The language of anti-immigration, justifications for drone warfare and surveillance tech, religious fanaticism, the oppression of the working class, the sense of god-given privilege for the upper echelons of society… The Machine is basically just asking a question that’s been asked over and over again historically – is it OK to sacrifice the few for the many? And all of the atrocities it alludes to were, in part at least, informed by that question, if not directly driven by it. So yeah, I think it’s still pretty relevant.”

I’ll admit that answer threw me. It wasn’t the game’s failure to go far enough, it was reality’s. Explicit references end because politics have synchronized back in line with the of the Victorian era. Instead of implicating culture at large, it is actually motivated by more specific national experiences.

This side to the game went unheralded, although it could have been indicated by a title change – Amnesia: A Machine for Manifesto Pledges? Anyway, a brief British politics primer for our international readers (bonjour!?): the current Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition government is often characterized as disproportionately enacting cost-cutting measures against the poor, reducing welfare support benefits and infrastructure while decreasing taxes for “wealth creators” to entice international investors.

Paired with the kind of self-awareness that sees Prime Minister David Cameron declare permanent austerity while sat next to a golden throne, initiatives like the unpaid Work Programme easily take on a seedy, Dickensian character.

So, as unarguably one of the bourgeoisie, how does this contemporary reality reflect on Mandus? He may be philanthropically minded, as documents recording his good deeds for his workers indicate, but any individual generosity is undercut by the systemic machinations of the clockwork AI that warps his industrial complex into a factory producing a new species fit to populate the capitalist world.

It can be argued that attributing this to mystical hoodoo diverts attention from real, knowable causes. However, I’d counter that – as representative of an embedded, self-perpetuating system that lives in large scale institutions – the effects that make an otherwise conventionally “good” man inadvertently serve unknowable exploitative forces have more dramatic impact than a relatable, psychologically traceable tale of self-interest. There’s something compellingly tragic about the futility of personal virtue. One human controlling masses only leads to automated systems that take on an inhuman life of their own. As Mandus comments: “I have carried this world on my back with its legs about me, damn this wretched soul, I am given birth to nothing but machinery”.

And what about the pigs? After all, the descent to inhumanity includes them too. Mandus’ ravings at the end include phrases like “They will make pigs of you all and they will bury your snouts into your ribs and they will eat your hearts!” simultaneously being wonderfully brutal while also hitting that metaphor regarding the death of compassion.

I and other commentators thought a clear influence from HG Well’s The Island of Doctor Moreau was evident. The 1896 novella, a speculative take written by a trained biologist, revelled in muddying the distinction between the animal and human. A crazed scientist populates a remote island with experiments resulting in sentient, upright animals that can be mistaken for brutish humans. With its preoccupations with brutality and humanity’s maladapted weakness for the modern age, it seemed an obvious connection. But, with my final question about why a socialist proto-science fiction author had such a prominent influence, I turned out to be off-base yet again.

“It wasn’t a conscious influence to be honest with you, but a lot of authors that were very influenced by him were – I was mainlining Stephen Hunt, GW Dahlquist, Lavie Tidhar whilst I was writing pigs, so I think that drifts in from there. And I definitely tried to get a sense of Lovecraft in there too, in that inhuman scale, trying to have a mentality and personality in the Machine that was both very human and utterly alien. And it’s definitely socialist, yes. For me, it’s a political game and I hope that comes over. We felt we wanted to say something, and the best horror is always a social commentary. Horror is always political. It’s a natural mix.”

Funny how the same ideas, which seemed so cleanly appropriated from Victorian writers, actually stem from writers working over half a century later. Horror isn’t just political, but stubbornly resilient. Laugh all you like at Twilight, but the core ideas fit into our modern reality despite their age. While new myths are always welcome, it seems the old ones still hold some surprises.

Francisco Dominguez is an English graduate currently pursuing a postgraduate career in stacking food. You can follow him on Twitter.