Games of 2014 (13/15)

Yet another five great games: Fract OSC, Dungeon of the Endless, Crypt of the Necrodancer, Oracle, and Bayonetta 2.

Fract OSC

Fract OSC embeds you in a world of music. Every structure around you exists with the sole purpose of producing music. Neon blue, green, and purple permeate the land, each marking a different path, a different track. You’re told nothing about where to go or how to interact. You’re simply left to wander about and figure everything out yourself, piecing together the rules and nature of this world as you go, just as you’re piecing together the threads of music that run through it.

It explores this through rudimentary puzzles: pushing blocks, directing beams, and rotating or elevating platforms. Occasionally, however, it discards these in favor of more direct interaction. At the end of each path lies a console that allows you to piece together the threads of music you’ve restored to form something new. You’re not merely dropping notes into a grid here, rearranging them until you’ve produced the desired tune, but taking excerpts and weaving them together into something whole: a track of your own creation. You’re limited by what you can do there, of course, and the goal is to produce something specific, but it’s still one of Fract OSC’s strongest moments. Because it captures the joy of making music.

The endgame goes further in that regard. Upon finishing Fract OSC, you’re taken back to the studio where it all started. Only this time, instead of seeing a bunch of locks on the screens around you, you’re greeted by a complete synthesizer toolset. Every piece of music you’ve helped compose over the course of Fract is here, waiting to be remixed to your heart’s content. After spending the whole game being nothing more than a helping hand in creating music, finally you have the ability to truly make something of your own, to leave your own mark on this world.

Callum Rakestraw is an videogame critic based out of Oregon. His work can be found on Entertainium and occasionally on his blog. You can follow him on Twitter.

Dungeon of the Endless

If there’s one thing the indie space doesn’t lack for, it’s dungeon crawlers. Whether you prefer to call them roguelikes, procedural death labyrinths or any other philological construction of your own choosing, a quick perusal of Steam, GOG, or even itch.io will yield myriad of games about progressing through a dungeon, fighting monsters, and collecting loot.

To be fair, this isn’t really the fault of any individual developer – a genre that’s known for its simplicity and lean design can only be stretched so far in terms of originality, and eventually games are going to start treading the same ground. This is why Dungeon of the Endless from Amplitude is so special.

Dungeon of the Endless is a game that takes the stress of progressing through room after room of increasingly tough enemies and mixes it with the stress of managing resources and player units in real time. An amalgamation dungeon crawler/tower defense game may not sound like it makes a lot of sense, but the extent to which the studio has tweaked, refined, balanced, and otherwise obsessed over the minutiae involved in making each seemingly disparate element of the game mesh is impressive.

The game is familiar enough in all its constituent parts that veterans of either genre will have a pretty good idea of what’s going on, but its presentation is unique enough that even practiced stalwarts will challenge themselves to learn the basics and, ultimately, excel.

Patrick Lindsey is a Boston-based game critic and occasional developer. He loves talking about narrative design in shooters so much that he’s writing a book about it. You can follow him on Twitter.

Crypt of the Necrodancer

Music is inherent, it’s a built-in part of who we are and how we understand the world. Life is defined, in a way, by the little rhythms. We set our alarms for the same times every day, we listen to the radio stations and music genres we most gel with, and we have rhythms so innate and complex that our bodies will rebel if we deviate too far, like headaches for failing to eat, or exhaustion for failing to sleep.

In that way, the concept behind Crypt of the Necrodancer speaks to us on a level even beyond conscious choice, taps into something so natural, inescapably primal, that we can scarcely imagine a way of life where we weren’t dominated by rhythms. It’s on a level that speaks very naturally to players, and accomplishes something inherent in us that feels so normal. Combined with a relatively slick interface, solid gameplay, and intriguing design, it’s hard not to love Crypt of the Necrodancer for how much it gets absolutely right.

Taylor Hidalgo is a writer by trade, longing always for professional work. He’s a fan of the sound of language, the sounds of games, and the sound of deadlines looming nearby. He sometimes says things on Twitter and his blog.

Oracle

Despite a penchant for brevity, and an unwavering, stationary perspective, Oracle can feel cavernous: its devotion is to awe-inducing sensations of detachment and introspection. It shows how compact play can address issues like the uncertainty of fate and the messiness of interpersonal communication.

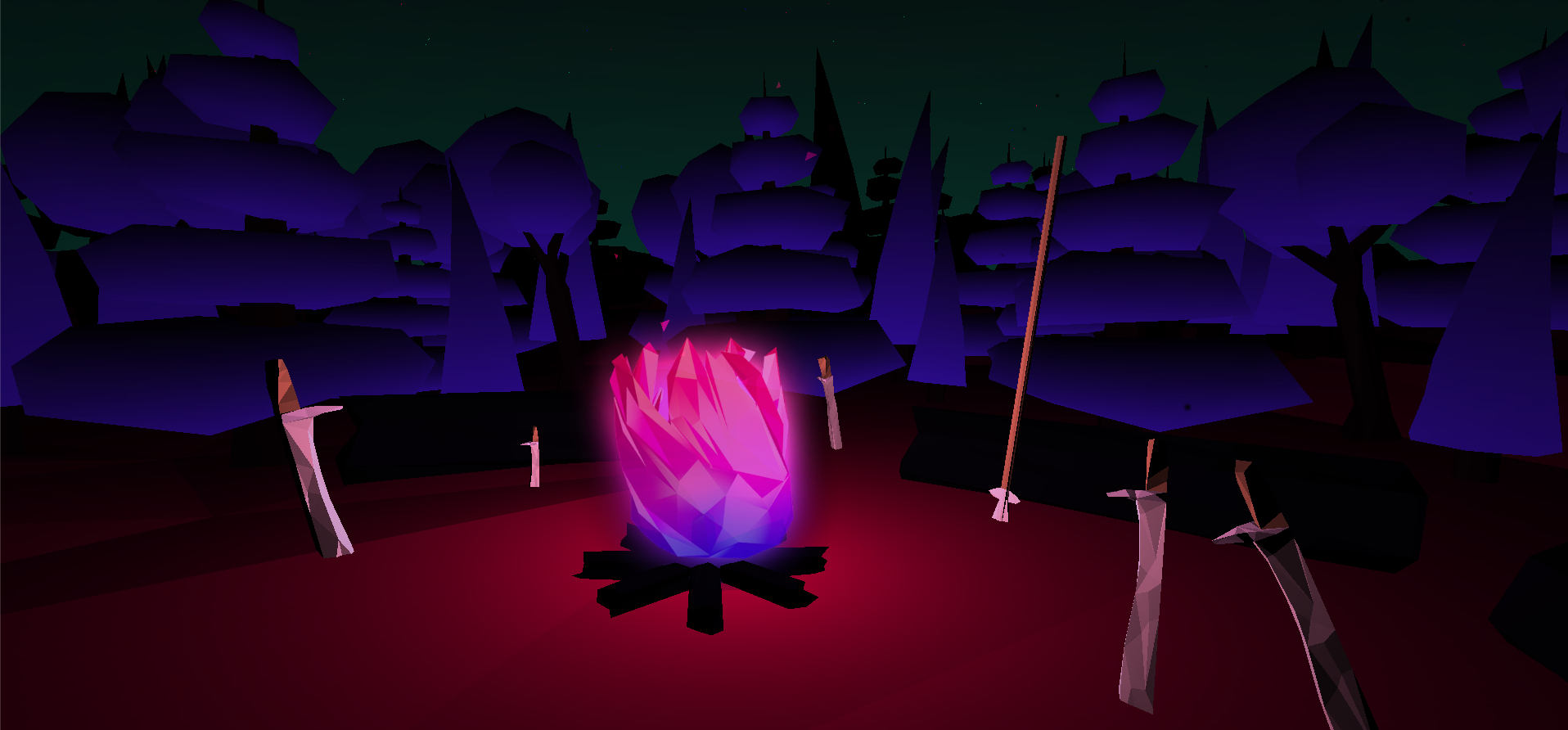

Crackling flame in the center and battered weapons discarded all around the campsite, Oracle’s framing evokes an otherworldliness, as if you just stumbled upon it in a meadow between purple trees, and the stars happened to align just right; a chance apparition, a dark snow globe you shake once every full moon to make time seem slower.

Strangers seek out the oracle for guidance, bodiless in bits of floating text that trigger visions, pummeled by undulating electronica. Creator ceMelusine fills these short flashes with pregnant symbolism; at once familiar and eerily removed from reality like shadow play.

After a vision concludes, players are asked to pick a number of text snippets, often just single words. In just a few lines, they make up the final prophecy, which the oracle then communicates to its visitors. Neither the words used nor the symbolism found in the visions necessarily shape up to pull on the same, internally consistent thread. The process is one of interpretation, not translation from imagery into language.

Although it is made clear that we are looking at this scene through the oracle’s eyes, neither the strange visitors nor the oracle itself are ever shown on screen. This allows the process of interpreting and transforming a message to take center stage. From the start, the oracle is not framed as just a window into the future, but rather as a means to defy the misconception that the window pane is clear and destiny lies right there, easily legible.

Oracle is deeply invested in the idea that fate is messy and obtuse, that its interpretation might do more damage than good. The oracle is not granted some ultimate power. It carries the echoes of a mythical figure like Cassandra, who could see the future but never avert it. Language becomes a cage. The oracle could just make the prophecy up on the spot, or might be cursed to remain the only one who understands the significance of its prophecies. Or the visitors do understand and we are simply cut off from their worldly fate, left to spin their tales in our heads. The low-poly aesthetic, too, lends the scene a kind of uncertainty, with its soft surfaces and loosely defined boundaries.

Oracle is short, its visions procedurally generated. Even when the screen flickers back to black and the game has ended, it does not feel like the oracle’s duty has come to an end. Somewhere beyond, the timeless ritual continues.

Philip Regenherz sincerely apologizes for the egregious theft of your time he perpetrated just moments ago. To claim much deserved vengeance, you may follow the evolving deterioration of his hopes and dreams on Twitter.

Bayonetta 2

If Bayonetta represents the apotheosis of the stylish action genre, the point at which devils can cry no harder, than Bayonetta 2 is a slight change of direction. No game could top the sheer spectacle of Platinum’s magnum opus, so the sequel rolls the whole experience in a coat of videogame sprinkles and blasts it through a kaleidoscope instead.

Bayonetta 2 is more vibrant as you battle through Heaven, Hell and back again, more interesting with new foes and weapons to explore and master. ‘Witch Time’, Bayonetta’s ability to slow time with a dextrous dodge, now has an equal and opposite alternative – ‘Umbran Climax’ unleashes the sheer fury of Bayonetta’s Wicked Weaves, pummelling even the largest of foes into a shower blood and gold. It’s a game full of delightful contrasts and exquisite details, where every new playthrough offers fresh discoveries. It’s got more hyper-kinetic action in one fight than some entire games. It’s breathless, daring stuff: the kind of game that makes you fall in love with videogames again.

I don’t know which Bayonetta I prefer. Bayonetta 2 is a more refined and consistent game, the rough edges polished to a dazzling gleam, but in doing so it loses a little of the outrageous charm that I found so refreshing. Luckily, I don’t have to choose, and can happily play both of them forever.

Bayonetta is a masterpiece. Bayonetta 2 is more of the same.

Alan Williamson is the Editor-in-Chief of Five out of Ten, blogs at Split Screen, and is a digital factotum for Critical Distance and VideoBrains. He is a self-exiled Northern Irishman living in Oxford, England.