2015: The Year of Triple A

Destiny, Bloodborne, Splatoon, The Order: 1886, and Soma kick off our look back at 2015.

Destiny

Destiny is that rare game which is noteworthy for the sheer quality of its writing. Not the plot or the characters or the dialogue, which are middling even in the much-improved The Taken King, but the sentences, the words on the screen and in the margins. If you had a Mac in the 90s and remember when Bungie’s shooters were known for that kind of thing, there’s a lot in Destiny that might excite you.

The bad guy in The Taken King is Oryx. He’s an evil alien king with an angry voice and the game ends when you shoot him enough times with a sniper rifle. It’s a bit of a linear story, but fine, just about as compelling as you’d expect. Seemingly just for me, though, there’s a 50-page novella, the Books of Sorrow, about the melancholy path that led Oryx into your crosshairs. It’s a work of impressive imagination and craft. What seemed during the game like Oryx’s shallow lust for conquest reveals itself to have been the worship of a particular praxis, a demonstration of the strength of his preferred metaphor in a war between metaphors.

Destiny‘s writers fight hard to elevate the game with that kind of stuff. Maybe it’ll never work, but it resonates with me as a person who tends to do the same: I’ve spent so many hours taking in the game’s landscapes, which are beautiful and vague like your favorite paperback sci-fi covers from the 70s, and imagining the kinds of stories which these worlds could support if only they weren’t trapped inside a videogame. It’s good to know that someone on the other side is doing the same thing.

It helps, too, that it’s a really fun videogame. You leap around Crouching Tiger style, you find the weapon that fits you like a glove, you chat and laugh with your friends for hours, never running out of things worth doing. And you get to do it all in an amazing place, a place which is both beautiful and eloquent. There’s nothing better.

Joshua Trevett is a freelance writer and editor. He mostly likes art when it’s weird, and that goes double for videogames. That’s how he knows games are art. His writing can be found in publications like ZEAL and The Arcade Review. For secret reasons, it would be best if you followed him on just two out of these three social media sites: Twitter, YouTube, and his blog.

Bloodborne

From Software’s Souls series has a reputation for being punishingly difficult, but what this boils down to is that they require you to pay attention to things that few other combat-focused games care about. Positioning, distance, and strike timing are all crucial to staying alive. Souls games are rarely as difficult as they are exacting. You can take risks when dealing with enemies, but the margin for error is so slim that you often end up regretting it. Bloodborne does away with shields, a series staple, and becomes even more exacting for it. The changed pace of combat can be a bit jarring if you’ve played a lot of Dark Souls, because certain play styles are much less effective than they were previously. The Estus flask, one of the series’ great innovations, is also absent, replaced by farmable health items, which feels like a step backwards.

That said, the game pulls you as strongly as ever. There are moments of pure frustration, naturally, but these rough edges have always been part of what makes the series special. When it works, it’s exciting and oppressive, empowering and nerve-wracking all at the same time. You get better at the game because you don’t have a choice, and the game doesn’t hold your hand, but trusts that you’ll figure it out. And you do figure it out, and that’s what is great about it.

David Thatcher worked in the games industry as a QA technician for 10 years, and is now one half of the indie games studio TriCat Games, handling the majority of the art and audio tasks. His personal site is at giraffe.cat.

Splatoon

In the seven months since Splatoon’s release last May, it’s remained the one constant in my gaming rotation. Other games came and went throughout 2015, but Splatoon’s delightful character design, changes to the online shooter formula, and the terrible puns in its Miiverse integration make it a joy to revisit. Initially criticized for a limited map selection and lack of game modes, Splatoon’s steady drip of game updates ended up creating a shooter that always had something new to come back to.

While all the weapons are decently fun to use, new types of weapons added over time heavily changed how I played. At launch, I was a staunch advocate of Chargers, Splatoon’s sniper equivalent. As the game progressed, I fell in love with the Sloshers – literal buckets – Splatings – Gatling Gun puns! – and even found a version of the Roller that I could appreciate. In a world of shooters where it’s “Burst Rifle/SMG or Bust,” it’s refreshing to constantly change how I want to play. I can’t think of any other game in which I changed my loadout on a whim, solely for kicks. Nintendo released the last set of updates to Splatoon in January, and I hope the announcement of Splatoon 2 isn’t too far off. Until then, I gotta finish leveling up all these sweet shoes.

aprettycooldude plays a lot of video games, listens to a lot of music, and sometimes even dabbles with making the latter. You can find him posting in a relatively SFW capacity on Twitter and likely much less so on Tumblr.

The Order: 1886

The Order: 1886 suffered undue criticism for being “cinematic” and for being short on “gameplay”, as though videogames should be pigeonholed into stricter, traditional parameters. Talking about a game’s length, or its linearity, or its reliance on cutscenes makes for boring conversation anyway. To this writer’s eyes, The Order: 1886 represents everything that big-budget, mainstream games should embrace, not discount. Its tightly authored narrative in a richly detailed world stands in refreshing contrast to prevailing trends in recyclable open-world filler like in Mad Max or quickly perishable entertainments of multiplayer-centric games like Star Wars: Battlefront.

The game warrants reconsideration not just as a mainstream title repelling the trends of empty open-worlds and unproductive multiplayer shooters, but also for its certitude in its art design.

Awash in a honeyed, candlelit glow, The Order: 1886‘s conception of industrial London as Dickensian steampunk envisions locales like they’re from charred antique daguerreotypes. There’s a painterly attention to detail with the game, scattering objects like vintage advertisements, faded paintings, and gadgets out of a Jules Verne or Sir Arthur Conan Doyle novel throughout its richly imagined world. Claustrophobic interiors are heightened by the game’s presentation in widescreen aspect ratio, conveying an ever-tightening sense of visual asphyxiation as its characters plumb the depths of working class slums. These forays uncover a greater conspiracy of vampiric global capitalism and the exploitative effects of rampant imperialism, lending The Order: 1886 a welcome politicized charge.

Indeed, The Order: 1886 addresses topics that most videogames rarely acknowledge: colonialism, class struggle, systemic corruption, globalization. It even focalizes such themes through a compelling woman of color, Lakshmi Bai, who the game later reveals as the real-life colonial resistance leader Rani of Jhansi and aligns its politics in favor of her class rebellion against the fictionalized English East India Company. As a game that calls into question all kinds of deeply entrenched institutions that govern society, its titular Order could very well also be called A Machine for Pigs.

Miguel Penabella is a freelancer and comparative literature academic who worships at the temple of cinema but occasionally bears libations to videogames. His written offerings can be found on Kill Screen, First Person Scholar, and Unwinnable, all of which are archived on his blog, Invalid Memory.

Soma

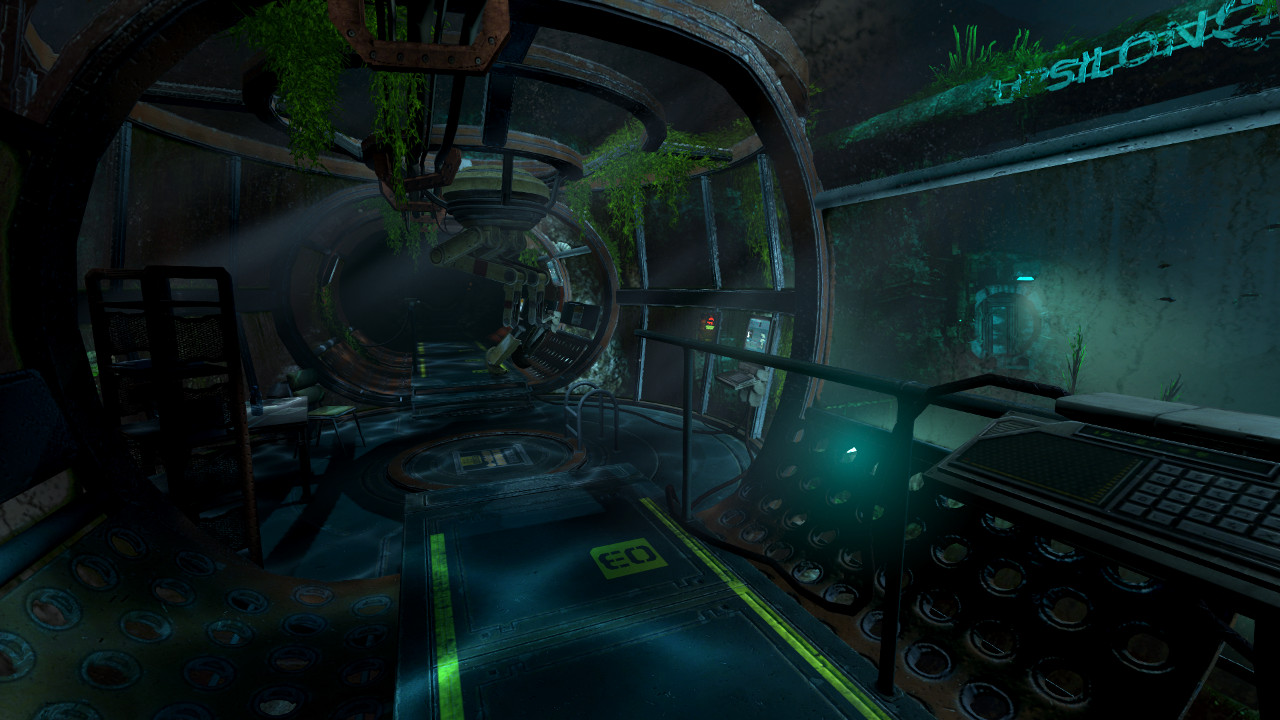

My love for Frictional Games’ Soma didn’t come easy, although it came to stay. Initially, I was merely intrigued by numerous enthusiastic reviews and it took me several attempts to get immersed in the game world. Sure, I admired the elegant introduction of the game – we meet the protagonist, learn of his terminal illness, experience his participation in an experimental medical treatment, and then wake up in the unsettling world of the underwater station Pathos 2 – but then Soma nearly lost me. The first stages of the game from the Upsilon complex of the station to the wreck of the research vessel Curie were well crafted, but felt generic and unconvincing to me.

It was only after two hours of playing, in the eerie corridors of the Theta complex and notably after the descent into the otherworldly Abyss that I got hooked and really lost my heart to the game. The tragic story of project Pathos 2, the cryptic accounts of the staff and the claustrophobic atmosphere captivated me. It combined the aesthetic of the 1989 movie The Abyss with a better story to back it up. Without weapons we are ultimately impotent when confronted with Pathos’ nightmarish but human monsters, and yet I still felt the urge to linger in dangerous quarters to learn more about the immediate past of the station. Although even the first encounters with opponents like the Construct and the Flesher left me with a feeling of unease, it was from Theta onward that I was genuinely terrified, my heart still pounding minutes after leaving the game.

While its aesthetic and mechanics were impressive, it was ultimately the narration of the game that enthralled me. Soma works so well because, at its core, it’s a metaphor for our most existential angst, for the precariousness of identity. In this sense, one of the most potent (ephemeral) images of the game was the disturbing reflection of the protagonists body in one of the mirrors: “And if thou gaze long into an abyss, the abyss will also gaze into thee.”

Eugen Pfister is a historian teaching at the University of Vienna, specializing in the cultural studies of videogames. He has a blog and tweets at @Trogambouille.