2015: The Year of Puzzles

We’re pushing boxes and connecting dots today with Cradle, Snakebird, Infinifactory, and The Talos Principle: Road to Gehenna.

Cradle

Cradle starts out with one of my least favorite plot points in fiction: memory loss. The good news is that it actually uses this in a highly intriguing and meaningful way. Within a very short amount of time, Cradle had me meticulously rummaging through every drawer and scrap of paper I could find. I wanted to know everything I could about where I was, who I was, and what I was.

Cradle isn’t a huge game in terms of physical space, but it does a lot with its few set pieces. The main hub of the game is a yurt where you initially wake up after having your memory wiped. The space is small, but filled with interactive objects and readable notes. Every new object or note you find adds a new piece of information about the unusual world you find yourself in. The game is a fascinating bit of world-building, and it will have you scratching your head with each new development in the story.

Cradle isn’t a perfect game, but it’s incredibly effective in creating a world and characters that you want to understand better. I kept wanting to unlock one more line of dialogue or find one more new clue. Once you start it, you won’t want to stop.

Jake Crump is a writer based in Louisiana, where he lives with his wife and three rescue dogs: Eliza Doolittle, Captain von Trapp, and Dorothy Gale. You can find more of his work on his blog, TheDweebJar, and follow him on Twitter.

Snakebird

Snakebird lulls you into a false sense of security with its bright, appealing visual style and wonderfully well-characterized creatures, but it’s one of the most fiendishly difficult puzzle games I have ever played. How quickly it reaches that stage is surprising, too. The first three short levels are essentially a tutorial introducing you to the basics, and then you’re suddenly presented with a number of puzzles that feel like they might be impossible. Obviously, they’re not, but when you aren’t familiar with the mechanics, they seem as though they might be.

The genius of Snakebird is how those mechanics get into your head, and encourage you to figure out how to do things, both when you’re playing the game and when you’re not. I remember getting stuck on a level and turning the game off, devising a solution in my head before going to sleep, and then trying it out the next day to discover that it worked. There are some levels that are easier than others, as they build on existing tricks and mechanics rather than requiring you to learn new ones, but the majority of levels feel completely overwhelming when you first encounter them.

Like the best puzzle games, though, the feeling of accomplishment that comes with solving them is dizzying. And it almost never feels like you arrived at those solutions by chance; everything clicks into place, and you learn from it. Snakebird is a criminally underrated puzzle game that I would love for more people to discover in 2016.

David Thatcher worked in the games industry as a QA technician for 10 years, and is now one half of the indie games studio TriCat Games, handling the majority of the art and audio tasks. His personal site is at giraffe.cat.

Infinifactory

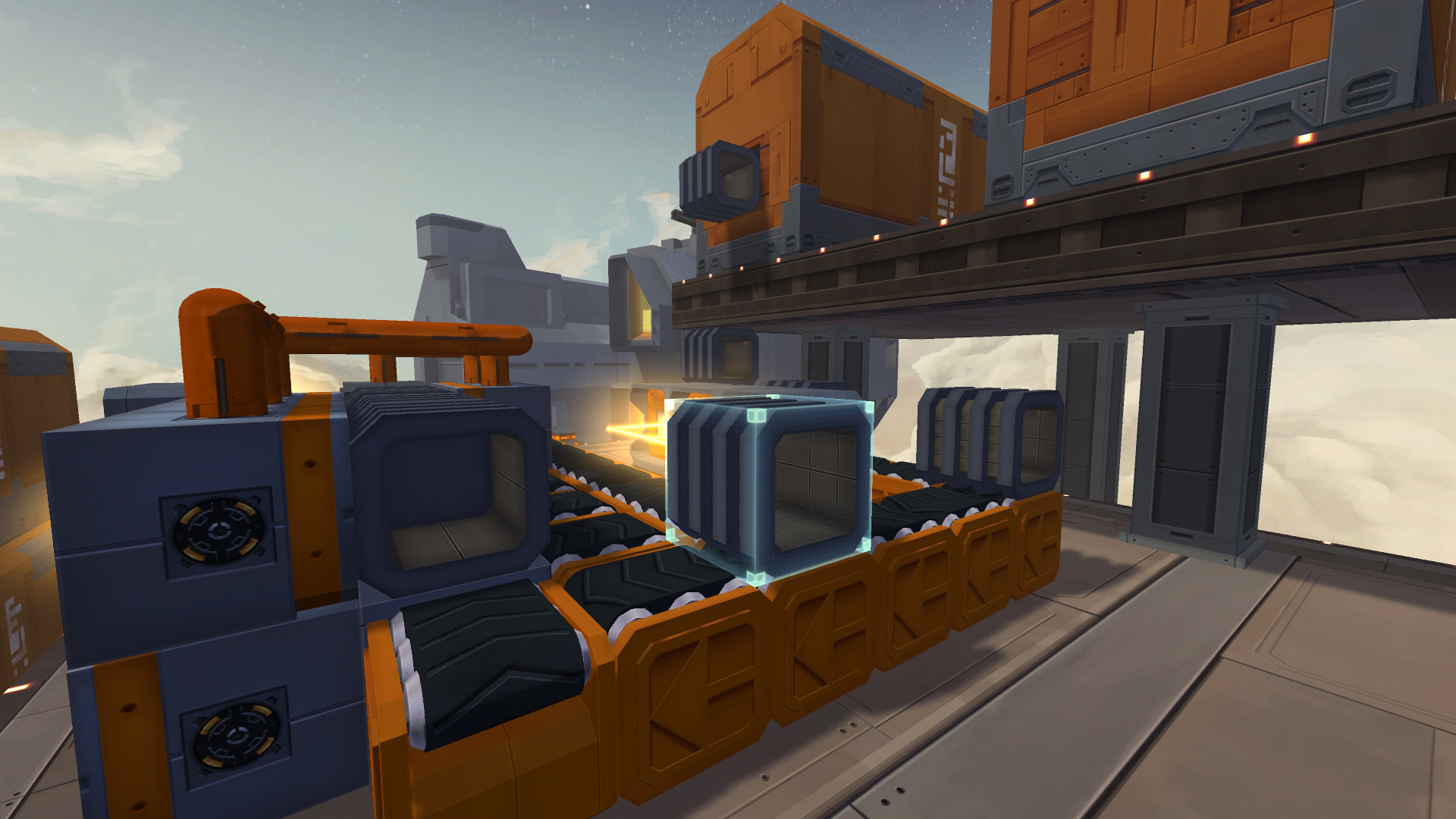

A smashed visor and a heart-breaking audiolog let you know that you aren’t the first one to try this and fail. But as you float around listening to a long dead woman wondering if she will ever see a cornfield again, you suddenly realize that if you shift that sensing module a step to the right, this whole production line will come together. That might mean another treat, maybe even a trophy!

I haven’t finished Infinifactory. I haven’t even played it in two months. But sitting on the loo the other day, I suddenly realized how to solve the problem I got stuck on. Sometimes the game that your hands are playing isn’t the one that your head is playing.

You won’t have a better time herding gerbils, or carving up a whale to feed your alien overlords. You won’t have a sexier time stripping a mining module for parts and sticking them back together. And nothing else can give you shivers of pleasure when you finally figure out how to put a bedroom together using only conveyor belts, plungers and some bright orange tubing.

At the end of the day, with your creation humming along like the well-oiled machine that it is, you soar into the sky and feel what the Lord felt when she looked down on her creation and saw all her logic gates working exactly as intended. But the Lord didn’t get histograms.

Dibs is a guy who likes histograms, even when they tell him he is distinctly average.

The Talos Principle: Road to Gehenna

The Talos Principle beat The Witness to the punch in December 2014. Both are games in which the player solves puzzles while the authors go out of their way to underline the artifice of it all, idly quoting humanistic philosophy. It’s the heavenly garden of knotted up roots, a place where weirdos like me love to go and untangle things forever.

In this formula, the quotations work best when they’re part of the scenery: there for your thinky brain to watch through the car window while your solvy brain drives. The Talos Principle curated that material well, but the narrative fell apart towards the end, when it had to bear the weight of all the epistemology and theology and other grandiose stuff that got brought up along the way. Trouble is, if you deploy this setting without a narrative thrust, it recedes into aloof sterility.

Quite a puzzle. The Talos Principle‘s DLC side story, Road to Gehenna, makes some progress toward solving it. Rather than linger on the nature of the world, it gets down to the proper work of telling a story about the characters who live in it. This corner of the setting, a prison reality where techno-god’s robot exiles make art in DOS and share it on a web forum, is ambitious and original, and the place really gets shaken up when you arrive to tell them it’s the apocalypse. If the story sometimes feels in danger of being vindictive – some characters seem to riff on broadly recognizable internet types – it eventually finds a kernel of empathy for every character, giving each a reason to be present.

I have a big, dorky appetite for these kinds of games. My version of morning coffee with the newspaper is the right scenery and a good puzzle. Road to Gehenna brings something else to the table, and that makes it special.

Joshua Trevett is a freelance writer and editor. He mostly likes art when it’s weird, and that goes double for videogames. That’s how he knows games are art. His writing can be found in publications like ZEAL and The Arcade Review. For secret reasons, it would be best if you followed him on just two out of these three social media sites: Twitter, YouTube, and his blog.