Opened World: Walled City

Miguel Penabella avoids the darker alleyways.

Immediately, Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days confronts players with a grimy Shanghai’s hidden underbelly. The titular protagonists are being tortured in some clammy washroom, completely concealed and far removed from the shiny, ultra-sleek representation of the Chinese metropolis in films like Skyfall. Gone are the sterile glass rooms and the elegant commercial districts catered to tourists and businessmen. Instead, Dog Days wants to pit players against the oppressive virtual architecture and materiality of its world, including the grime, dirt, congestion, garbage, and crowds that comprise it. In the first issue of the magazine Heterotopias, critic Gareth Damian Martin notes how the game’s Shanghai is a city that shelters violence, and its digital feel produced by camcorder pixelation and blown-out overexposure marks it as an unfamiliar “city turned inside out.” Others have written about this low-fi aesthetic (including two pieces of my own), but less has been said about the materiality and social and architectural contexts of this Shanghai setting itself.

Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days depicts transition, poverty, and the marginalized. In an interview within Heterotopias conducted by Martin and the game’s art director Rasmus Poulsen, the latter underlines an interest in showing unseen parts of the city such as alleyways and corridors lined with trash. Dog Days is a game about the ugly infrastructure of a modern city. Poulsen calls it “a love letter to the leftovers,” channeling players through liminal spaces like a partially renovated airport and a skyscraper construction site where half of a building is there and the other half is non-existent. Even beyond the trash and the back alleyways, the game explores the human beings who are similarly discarded and concealed on the margins of society. By routing the player through overcrowded tenement buildings and dingy sweatshops, Dog Days also allegorizes the effects of late global capitalism on human bodies. The mangled flesh of Kane and Lynch as well as the numerous non-player characters encountered in the peripheries reflects the bodies spit out in non-Western, economically developing regions of the Global South. Bodies are shown among the detritus of Shanghai’s alleyways and enclosed in the towering architecture. For the game, the city is not a gleaming destination but a suffocating site of oppression that must be escaped.

China’s rapid development in the past few decades has produced (and continues to produce) uneven distributions of wealth where underprivileged classes of Chinese society are so often left behind. Through the game’s gritty and squalid art direction, Dog Days visualizes the stark reality of urban impoverishment. Rasmus Poulsen’s studio Technouveau describes their artistic approach on their site, explaining, “Pre production experimentation focused on the vague poetry of urban loneliness, as well as the aesthetics of ubiquitous cheap camera lenses and their signature visual artifacts.” This vague poetry of urban loneliness neatly encapsulates Shanghai’s role as a city of migrant workers, where laborers from the countryside leave the comforts of family and home in search of work in an unfamiliar, isolating cityscape. Martin calls Shanghai a “city of strays”; the migrant workers institutionally marginalized or publicly ignored represent this unseen demographic. While poverty in China has been generally decreasing, new problems arise as the country emerges into the late stage of global capitalism: wealth inequality and labor exploitation, brought about primarily by a boom in migration to cities. POVERTIES, a site that supplies information on the relationships between economic development and humanitarian issues notes an internal migration of roughly 250 million people fleeing the Chinese countryside to relocate to cities for work. These migrant workers lack access to basic rights due to a discriminatory internal passport system that ends up producing an undocumented, migrant underclass. This practice—the hukou system—requires residents to register as either “urban” or “rural,” and migrants from the countryside are often denied urban status when they move to the city. Undocumented, they are denied access to city healthcare, education, employee housing, etc. Consequently, they must make do with their situations and intermix with the rest of Shanghai’s body politic in creative, often illicit ways.

Urban housing for migrant workers consists of cramped, claustrophobic tenement blocks and alleyway homes that squeeze in between the larger infrastructure of a constantly expanding city. These spaces are the battlegrounds of Kane & Lynch 2, in which the protagonists rush headfirst through panicked crowds and snake around circuitous labyrinths. In an excerpt from a book on housing in Shanghai by Harvard professor Jie Li, traditional designs of Shanghai residential compounds are noted as having a courtyard layout where boundaries are porous. The fierce firefights of Dog Days occur as Kane and Lynch crash into these apartment blocks to rescue Lynch’s girlfriend. Gunfire is exchanged across the empty spaces of a courtyard from one balcony across the way to another, colliding into targets from afar. Both enemies and the protagonists dart into rooms, delving deeper into endlessly subdivided interior spaces. The game replicates the porousness of the city’s residential architecture, and the interior/exterior divide is often ill-defined. Characters break down doors to reveal other potential paths and dead ends. In one notable moment, Lynch kicks down a door only to find that it opens onto a sheer drop. The connecting building has been torn down, leaving only ruins like a blown-out ribcage. Even entire city blocks are just as easily discarded as the piles of garbage that line the game’s dark alleyways.

The very architectural layout of Shanghai in the game reinforces themes of entrapment and claustrophobia, translating well into a story about the futile desperation of itinerant criminals on the run. We can consider Gregory Byrne Bracken’s examination of Shanghai architecture in The Shanghai Alleyway House: A Vanishing Urban Vernacular, where he notes that its urban housing contains “few entrances, invariably gated, with many dead-ends.” (A shame we never got Whore of the Orient, another game about Shanghai that could have provided crucial historical framework for the labyrinthine passageways of the city.) Similarly, Rasmus Poulsen remarks on the iron gates and closed doors of Shanghai in the aforementioned Heterotopias interview, in which gates and locks leave players feeling as stuck as the characters that occupy these spaces. Kane & Lynch 2’s blockages damn the player to the immediate griminess of slums even as the game tantalizes with views of a faraway vista of modern skyscrapers. The game suggests the ubiquitous closeness of wealth and modernity but keeps it always beyond reach. Moreover, parking garages burrow beneath the urban tangle aboveground, hinting at a hidden subterranean world. These underground spaces connect with shopping centers with halls that emerge onto city streets once more, again reflecting the porousness of Shanghai’s indoor and outdoor worlds. Kane and Lynch, lacerated like butchered pigs, spill between these spaces in a burst of gunfire and breathless in their flight from the chokehold of the city.

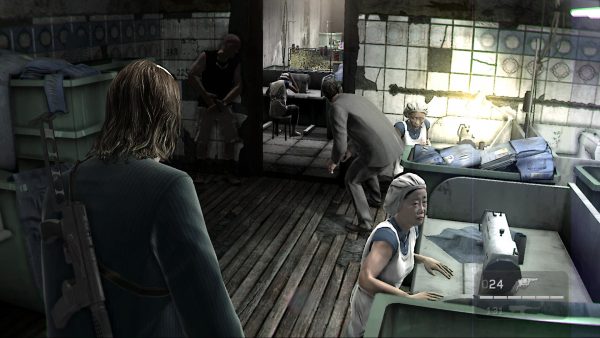

Kane and Lynch may be trying to escape Shanghai after finding themselves locked in a pattern of oppressive violence and corruption, but for many low-income workers, Shanghai is their permanent home. An oppressive capitalist structure tethers the multitudes of migrant workers in place, and Dog Days does not shy away from depicting this subjugation. The protagonists will stumble into dozens of industrial zones throughout their exodus, including a prison-like sweatshop locked deep within the windowless core of a building. Yet as Kane and Lynch progress through these spaces, players can discover adjacent rooms furnished with bunk beds. This small detail is shocking in its casual fleetingness; we’re not just trespassing on a workplace but a home. Not only do these sweatshop workers toil in these horrid conditions, they also live here completely excluded from urban sociality and concealed from the public eye.

Despite these immense hardships, the migrant workers of Shanghai still make this city habitable. An early sequence through an open-air meat and fish market shows the residents of Shanghai operating their daily businesses, somehow making a living out of the poorest areas of the city. These are places of human activity and action, of people reacting to an oppressive system by creating alternative commercial arteries outside the legal strictures of the city. Later in the game, the protagonists will barrel through a cheap DVD store in a less than reputable neighborhood, and it’s clear that this space is an illegitimate business. These residents must confront the many rules meant to consolidate a city replete with cultural densities, carving out a niche by altering the spaces for work, inexpensive goods, and community in an otherwise massive city. Kane and Lynch may not think twice about stampeding through such areas, but the NPCs that inhabit these locales reflect the real people of Shanghai who circumvent the formal mechanisms of work and citizenship by redistributing these spaces. Night markets provide opportunities for work in a city in need of jobs and grant people on the periphery with a sense of agency to find commonality and inclusion.

Of course, the threat of late capitalism still looms in Kane & Lynch 2, and this malignant force is embodied in the aforesaid skyscrapers that always loom in the distance as a constant presence. In addition to residential housing, Li also writes about the “ceaseless re-writing of Shanghai’s surface” as older structures are indiscriminately bulldozed to make room for modern skyscrapers. With the flood of transnational development in the new millennium, congested alleyway homes are found nestled side-by-side with modern towers housing international businesses, and the alleyways themselves are in constant danger of demolition to make room for the demands of globalization. In Dog Days, transnational capital visibly marks the landscape with the sign of the antagonistic institution pulling the strings; a building emblazoned with the words “NEW MONEY” in all caps suggests aggressive takeover and marking of territory. When the rich and poor collide in the game, they do so with violence. Li suggests that Shanghai has a “palimpsestuous history” of constant rewriting and tearing away; that sense of palimpsest emerges in the art design of the game. A firefight in a construction zone heralds a new skyscraper where once there might have been a historic residential block. Instead, the space is gutted and torn, suggesting the “aesthetics of constant change” that Martin describes. The city’s constant demolition and mutation renders the city virtually unrecognizable years later. This world seems to have moved on from the poor and from Kane and Lynch. The city serves as a kind of totalizing eraser so keen to flatten the livelihoods and homes of people in favor of constant change, simultaneously squeezing and walling-in those who have no opportunity to advance in society or escape undamaged.

Regardless of how one chooses to read Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days—its criminal nihilism, unreliable narration, camcorder voyeurism, and portrayal of the corruption of militarized police all warrant careful scrutiny as well—the game packs an immediate rawness which has gone critically under-examined. Even beyond Dog Days, so many other thoughtful games are entangled in these issues of regional disparity, displacement, and the chokeholds of late capitalist development in urban spaces such as Max Payne 3’s favela sprawl or L.A. Noire’s investigation of postwar capitalism and housing. In Dog Days, developer IO Interactive taps into the institutional violence that undergirds the contemporary global city. Kane and Lynch may fly away from Shanghai at the end of the game, but they do so only by desperate force. When the camera lingers on the closing shot of their escape plane disappearing into the night before the camera drops dead, we must also consider the multitudes of people who are similarly unable to find escape.

Miguel Penabella is a freelancer and comparative literature academic who worships at the temple of cinema but occasionally bears libations to videogames. His written offerings can be found on PopMatters, First Person Scholar, and Unwinnable, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.