Due Diligence: Never Going Home

Leigh Harrison encounters his younger self.

When I was younger I used to take the last line of Slurring the Rhythms — “we’re never going home” — very literally. I was a teenager, so, like, I literally couldn’t help myself, okay? Laura Jane Grace sang most of Against Me!‘s early songs with the sort of snarled aggression you’d expect from a lefty, politically-minded punk band, and this one’s no different. Except for its final line. After a couple minutes shouting about severing burdensome ties and life on the road with a band, she clears her throat and just speaks, as if stating a simple fact: “we’re never going home”. “Exactly,” my young mind thought, “why go home when you’re in a fucking band?! That’s soooo cool!”

It’s well over a decade since I first heard the song, and I’m more emotionally mature than I was at 15. Probably not as much as I’d like to think, but there you go. “We’re never going home” isn’t Grace matter of factly saying we’re never going home, is it, Leigh? No. She’s saying we’re never going home, whether we want to or not, because You Can’t Go Home Again. We can’t go back and be young again; we change and things get lost along the way. This simple realization is why I cried a lot at the end of Life is Strange.

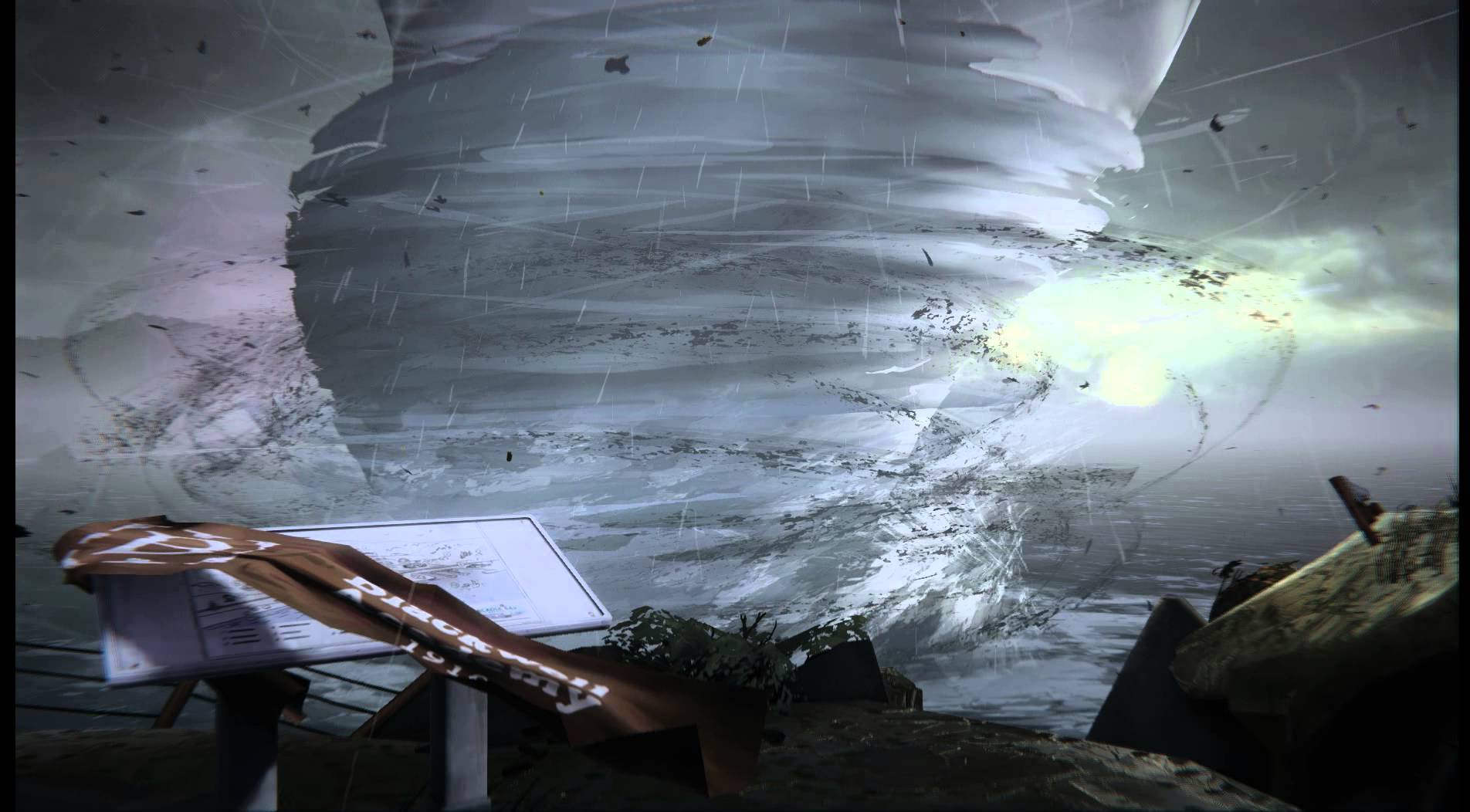

Life is Strange is a coming of age story wrapped up in a murder mystery/time travel sci-fi. Our protagonist is Max Caulfield, a kinda socially awkward 18-year-old who returns to her childhood hometown of Arcadia Bay after five years in the big city. She enrolls at Blackwell Academy to pursue her dreams of being a photographer, and then her life falls off a cliff. First, she has a premonition the town will be destroyed by a tornado in four days (helpful newspaper flapping in the wind), and then discovers she can rewind time and on special occasions travel huge temporal distances through Polaroids (“I just don’t like digital”).

What follows is a tale of teen angst, lifelong friendship building, youth vernacular I’m now too old to connect with (for realz/hella/txt spk/emojis), time tinkering, and the hunt for someone who might be a killer. (HINT: it’s not the creepy gardener or the hard-ass, war vet David.) Being an adventure game, Life is Strange is equal parts tedium and intrigue, with the experience pivoting around the quality of the storytelling. Fortunately, even the its most mundane narrative beats are utterly compelling, thanks to its deft understanding of what it feels like being forced to grow up.

Max didn’t just leave behind her childhood home when she moved to Seattle. She jettisoned her BFF, Chloe, who she missed so much she failed to even contact once in five years. In the meantime, Chloe filled the gap with things my own teenage years were replete with: booze, cigarettes, hijinks, punk rock, and gentle mischief. She’s the sort of middle-class rebel lots of us either were or knew. Safely obnoxious, she’ll often flip from charming to petulant for no reason — but normally only when someone tells her what to do.

She’s destined to grow out of all this, though, as we all do, and will probably end up a marketing executive or brand manager by 25. Sadly, she won’t have the chance to pursue these exciting and creative career paths, because she dies right at the beginning, and many more times throughout the game. And herein lies Life is Strange’s major hook.

She’s destined to grow out of all this, though, as we all do, and will probably end up a marketing executive or brand manager by 25. Sadly, she won’t have the chance to pursue these exciting and creative career paths, because she dies right at the beginning, and many more times throughout the game. And herein lies Life is Strange’s major hook.

Max reunites with Chloe in the bathroom at Blackwell (while taking a Polaroid of a BUTTERFLY, geddit?!), where the fierce anarcho-punk is in the middle of an argument over drugs with resident spoiled rich kid Nathan Prescott. He’s suffering from mental health issues and behaves erratically, and on this occasion goes a bit too far and shoots Chloe. He’s instantly repentant, but the damage is done and she bleeds out then and there. While Max doesn’t recognize the dead girl as her best friend, owing to Chloe’s anti-authority blue hair and ripped-ass skinny jeans, she’s the wholesome sort, and the death of anyone concerns her.

This harrowing scene awakens something in Max, who promptly learns she can rewind time. Using her newfound power, she heads back two minutes, this time hitting the fire alarm to distract Nathan and averting her long-lost friend’s untimely demise. The two then jump in Chloe’s truck and ride off like a teen approximation of Thelma and Louise — wake of destruction in tow and all.

While out on the road we learn more about Rachel Amber, Chloe’s replacement for Max, who disappeared six months ago. Did she get on a bus to L.A.? Is she in trouble? Or worse? Also, who’s drugging teenage women at campus parties, and is this connected to Rachel vanishing? That’s what the dynamic duo set out to discover. In typical murder mystery style, the town is full of suspects. If it’s not the obvious creepy guy or possibly demented veteran step-pop (again, it’s not), then it might be the local drug dealer, the Principal, or the mysterious billionaire father of Nathan Prescott.

The pair follow many lines of investigation, breaking and entering their way around Arcadia Bay in a heartwarming microcosmic road trip. They haven’t a clue what they’re doing, obviously; they’re 18 and are too often swayed by their subjectivity, seeking evidence to back up their prejudices rather than actually detecting stuff — no, it isn’t “step-douche” David, however much you’d like your mom back, Chloe.

Their actions should be laughable, given they treat their romp with the same wide-eyed glee they did childhood games of pirates. They get so caught up in amateur sleuthing that the threat of a possible abductor/rapist/killer appears to fly right over their heads. But then you remember they have time travel, and their youthful devil-may-care attitude begins to fit snugly. At my count Chloe dies on five separate occasions, only to be save by Max and her powers. Smooshed by a train? No bother, just rewind and get her out in time. Shot (three separate times)? Easy. So while the stakes are high in terms of discovering the identity of the antagonist, the breezy lack of consequences lends the plot a youthful abandon more akin to regular teen hijinks like smoking in school or skipping class.

Their actions should be laughable, given they treat their romp with the same wide-eyed glee they did childhood games of pirates. They get so caught up in amateur sleuthing that the threat of a possible abductor/rapist/killer appears to fly right over their heads. But then you remember they have time travel, and their youthful devil-may-care attitude begins to fit snugly. At my count Chloe dies on five separate occasions, only to be save by Max and her powers. Smooshed by a train? No bother, just rewind and get her out in time. Shot (three separate times)? Easy. So while the stakes are high in terms of discovering the identity of the antagonist, the breezy lack of consequences lends the plot a youthful abandon more akin to regular teen hijinks like smoking in school or skipping class.

Because of this levity, the main thrust of the murder mystery plot only serves to keep us interested long-term. The friends’ rediscovery of one another is the game’s real preoccupation. Initially, Chloe is bitter as hell, her life taking a much different path to our protagonist’s. Just before Max moved away with her nuclear family, Chloe’s dad died in a car crash and she went off the rails. Now involved with drugs, drinking, partying, and every two-bit hoodlum in Arcadia Bay, she’s pissed. Her teen rebellion runs deep, not helped by Rachel Amber’s disappearance, which has sent her into a whirlwind of self-destruction (though, like most of us at 18, she actually loves life and just really wants the attention and excitement). Still, she needs Max, and the stability she represents, an awful lot.

Their friendship is two-sided, however, and Chloe gives as much as she takes. Beyond being in love with photography, Max is pretty rudderless. The product of a wonderful upbringing, she has no experience of hardship or pain, and so hasn’t really got much to say for herself beyond a pedestrian understanding of “right and wrong”. Chloe changes all this, showing her exactly what heartache and strife mean, and helps her understand that they can strike anyone at any time, irrevocably changing the people they touch. She helps Max see that the world can be ugly, even for the most beautiful of souls.

Their joint awakening is nuanced and touching, as is their growth as characters and newfound maturity. Summarising it would be an impossible task; suffice it to say that by the end of the game their bonds are stronger than ever, as their friendship transitions from childhood to adulthood, carrying with it all the added emotional depth you only truly find once you’ve grown a little.

At the game’s climax we’re presented with a choice. Turns out the tornado premonition was true; Arcadia Bay is about to be decimated, and what’s more it’s all Max’s doing. While she did discover Rachel Amber’s fate and the identity of the mysterious bad guy, all her meddling with time is about to bring about a mini end of the world (don’t worry about it, it’s a metaphor). She needs to make a choice: leave the entire town to the tornado and ride off with Chloe, or travel back through the foreshadowing butterfly Polaroid, to before the bathroom shooting, and just — let her die.

I obviously choose the latter, because that’s clearly the proper ending.

I obviously choose the latter, because that’s clearly the proper ending.

Now, this is sad in itself, yes, because Chloe dies. But it’s not why I burst into tears. In going back to before the shooting, you’re erasing their entire second go at friendship. Chloe dies on that bathroom floor having not seen Max since they were 13, since her best friend left her alone just after her dad died in an auto wreck. She instantly returns to being childish, angry, reckless — and quite frankly annoying — Chloe. She’s robbed of her epiphanies and hard-won lessons, of her painful transformation from adolescence to adulthood. And Max, being a time traveller and remembering everything she sees and does, has to live with this for the rest of her life. Their friendship, effectively, never happened.

This all resonated with me very deeply. It won’t come as much of a shock to you, though it did me, but I’m getting older. And I’m starting to feel it. Not physically, but emotionally. I moved away from my own childhood home about a decade ago, at 18, but unlike Max I’ve never returned for more than a couple weeks a year. Now, with a mortgage, and the inevitable marriage and kids snapping at my heels (neither unwanted, I might add), I’m beginning to think about the things — the people — I’ve lost. I still see most of my oldest friends and my family, but it’s little and not often. Where would we be now given different circumstances?

I frequently worry that my friendships will just fizzle out to nothing, that people I’ve known for nearly 20 years will go back to being strangers. Will you want to turn up next time I’m in town? Will you let me know if you’re ever in the heartless, money-centric, tourist trap, polished-to-a-sheen cesspit of London? Will I ever, ever see you again? I know these things are disgustingly self-centered and maudlin, but I think about them quite a lot.

Life is Strange struck such a chord because it answers all of my questions with the most probable and heartbreaking answer: no. We’re never going home. We can’t. We move through life, we grow, we change. Everyone does, and this inevitably means we lose parts of ourselves and others on the journey. Knowing all this is one thing, but learning to accept it is something else entirely.

A lot of time travel stories urge us to be happy with our choices by showing us how horrible the alternatives could be. Life is Strange is different, in that it portrays these surrogates to be illusory. We have one shot, the game tells us, so we best make it count. In this way, beyond the tears and horrible realizations, it’s actually rather life-affirming. It might be time to pick up the phone and call home.

Leigh Harrison lives in London, works in communications for a medical charity, and owns a hamster. He likes canals and rivers a great deal, and spends a lot of his time walking. He occasionally says things about videogames on the Internet, and other things on The Twitter.